Eyewitness media (not UGC): Newsrooms must handle it better or risk losing out

Sam Dubberley

is co-founder/director, Eyewitness Media Hub @samdubberley

Damage to Dublin airport plane, tweeted by Emily Carroll @EmzCarr

It’s no revelation that eyewitness media - video and pictures captured by those who happen to be at the scene of events - is now a mainstay of breaking news.

We saw it in its starkest, most immediate, most visceral on 7 January when many of us unwittingly clicked and watched the final moments of Ahmed Merabet, the first police officer at the scene of the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, after his shooting was retweeted by news organisations and individuals alike. Eyewitness reactions to the Paris events from all over the world were gathered, repackaged and used by news organisations to tell the story.

We’ve written a series of thought pieces around some of the questions raised by the Paris events. It is the very issues that we raise in these posts - from ethics to copyright - that compelled us to launch Eyewitness Media Hub at the end of 2014. We believe that news organisations have to address the logistical, ethical and legal challenges surrounding eyewitness media relating to ownership, consent, safety and critical consumption. And if we don’t there could be trouble down the road.

One of our goals is to move on from discussions about verification. Skill levels and commitment to it may vary - and our research published last year with the Tow Center for Digital Journalism highlighted the variance that exists - but newsrooms know it needs to be done and most have at least one dedicated journalist who is good at establishing the authenticity of photographs and videos shared online. Verification is part of the vernacular, editors recognise its importance, and there are an increasing number of experts now routinely debunking and confirming stories (Craig Silverman’s useful Emergent project, for instance). So it’s time for newsrooms to take the next steps and understand how to handle this content.

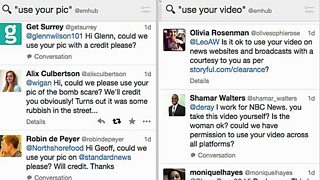

Many of the questions raised by Paris are also being raised on a daily basis for the smallest of stories. Open up your TweetDeck and do a search for 'can we use your photo' or similar and you’ll see how dependent newsrooms have become on including eyewitness media in their output.

But let’s get one issue out of the way first: the term user-generated content (UGC). This has been a contentious phrase for quite a few years now, with a definition so broad and awkward that it cannot accurately describe the phenomenon that we are focused on. It feels impersonal, ignoring the fact that a person, an individual, has borne witness to an event. That event may be mundane (a sunrise used in a weather report); it may be spectacular (meteorites falling out of the sky in Russia); it may be traumatic (Paris). Whatever it is, the evidence has been captured by an eyewitness - hence we say let’s leave UGC behind and use the term ‘eyewitness media’.

So what does moving beyond verification actually mean? First and foremost, it means looking after the eyewitness. Going back to Paris, Jordi Mir, the unfortunate eyewitness to and uploader of the video of Ahmet Merabet’s death, has told Associated Press of his regret about sharing the video.

Even though Mir requested news organisations not to show the moment of death (at one point a sine qua non of journalism), many around the world did.

Secondly, it means encouraging newsrooms to consider the legal and ethical complexities of crediting and copyright.

Thirdly, it’s about management being aware of the pressures their staff may be under when spending time looking at this content.

Tweetdeck displays typical requests to use eyewitness content

In the TweetDeck search example, one of our most stark observations is the questionable etiquette surrounding permission requests. The question 'can we use your photo?' is rarely accompanied by 'are you OK?' or 'are you safe?' or, even, 'did you take this?'. Any reference to crediting or licensing is usually glossed over, if mentioned at all, and often these ‘accidental journalists’ are placed under extreme pressure to respond immediately.

When Emily Carroll witnessed a collision between two planes on the tarmac at Dublin Airport at the end of 2014, she tweeted some photographs from her seat on the plane. Within seven minutes she’d received a usage request. Over the next few hours she received more than 20 others. Of the 26 requests tweeted to Emily over the course of the day, only one asked if the pictures were hers; two asked if she was OK; and seven mentioned that they would credit.

Having patiently agreed to most of the requests she received, Emily appeared to license her photographs through an agency eight hours later. So what would that mean for the consent that she had already granted to other organisations? And should she have been expected to make informed decisions while still seated on the plane having just witnessed a distressing event?

Many eyewitnesses feel they are performing a civic duty by reporting their experiences on social media, and accept the instant demand for their content by picture desks and journalists as inevitable. But how might they feel when content they have shared for free then contributes to the increased traffic, readership and in some cases advertising revenue for news sites?

One eyewitness who negotiated a fee with the Mail Online to use his photo of a small fire that broke out at Charing Cross station last November went on to experience serious bullying from other Twitter users who objected to him trying to profit from a potential tragedy. Other users supported his decision, suggesting that the news sites should definitely pay if they wanted to use his photo. This really is unchartered territory for both newsrooms and content owners.

At News Xchange 2014 in Prague, we created a partnership with Storyful to run a panel and workshop on eyewitness media. To both of these we invited along copyright expert Adam Rendle. We’d seen lawyers speaking about eyewitness media and copyright issues at other conferences and were never really satisfied. They frequently spoke about the grey area of what journalists can get away with in terms of using content without permission, but if newsrooms don’t start to appreciate how much crediting and labelling is a real issue it could seriously impact the current access they have to this content.

Our research reflects these concerns, with one senior rights person telling us “this could get [those who disregard credits] into hot water to such an extent that we can't use [UGC] anymore.” Adam raised many serious points, not least that it’s crucial for editors to understand what “fair use” is and means in a copyright context. For example, if you don’t credit then any chance of using a fair use defence goes flying out of the window.

And the consequences for newsrooms from a legal perspective are not the only consideration. Failing to accurately attribute can also have a negative impact on your brand. We wrote about Tom Warners and MH17 over the summer. Tom, an aviation enthusaist from the Netherlands, snapped a shot of MH17 taking off on its ill-fated flight from Schipol, which he then posted to his Twitter account. This generated a lot of 'can we use your picture?' questions to Tom’s timeline, including one from the BBC. Taking the conversation offline, Tom agreed, but requested a credit. Unfortunately, this credit did not materialise when the shot was aired initially and Tom made clear his anger at the BBC in later tweets, damaging the BBC brand in however small a way.

Eyewitnesses are becoming increasingly savvy and more aware of their rights, which means news organisations should now be building crediting mechanisms into their workflow. A common response in our research interviews with senior editors and producers was “we are often too busy getting the content to air.” But would that excuse fly if a news organisation sought to use a direct competitor’s content through fair use?

This is even more important online. Many news sites often scrape eyewitness media from the platform it has been shared on, brand it with their own logo, and present it in their own media players with obligatory pre-roll advertising, instead of embedding or linking to the original. Take, for instance, the now-debunked Syrian Hero Boy story (there's a more in-depth study on that by us).

The fact that several newspapers still uploaded the video to their own media players and went to such lengths to make it appear as their own, despite serious concerns that it was unverified, seems to us at least to be crossing ethical lines.

Finally, our third area of interest is vicarious trauma, which can occur as journalists scour YouTube and other networks in an attempt to discover and verify eyewitness media. The process takes a lot of work and often means exposure to content that will never be aired, never be embedded, and shouldn’t be seen by anyone. Vicarious trauma occurs through the emotional residue of the pain, fear and terror endured by the subjects of some eyewitness footage. Our research suggested that, although some newsrooms are aware of this and take steps to protect their staff and colleagues, many more do not. Those that do not tended to have the senior management culture of 'it’s no different to anything we saw on the ground in Iraq/Bosnia/Kosovo.' Except it is.

Feinstein et. al, in the first research into this phenomenon, conclude that there is “evidence suggesting frequent exposure in the newsroom to images, often live, of great violence can prove emotionally unsettling for a subset of journalists”. They note that, “as both the newsroom and journalism evolve in response to a rapidly changing world, new healthcare challenges will present themselves.”

So this is why Eyewitness Media Hub was launched. It’s about pushing news organisations to handle eyewitness media sensitively, responsibly, and in a way that is sustainable. We want to involve journalists in this discussion and ensure that the eyewitnesses - the content owners - continue to provide footage that helps us understand the chaos around us. We want to take this conversation further. Do let us know if you have anything to add.

Eyewitness Media Hub is a non-profit initiative. To help us secure funding, please sign up and show your support at Eyewitnessmediahub.com so that we can demonstrate the demand for the work that we do.

#CharlieHebdo: Minute-by-minute decisions over UGC

Safety issues with user-generated content (UGC)

Trauma in journalism video, presented by Sian Williams

Our journalist safety section deals with various aspects of trauma

How to make the most of user-generated content