Inside a tornado

NARRATION: Wherever you live on the planet, weather shapes your world. Yet for most of us how it works is a mystery. So, I’m going to strip weather back to basics, uncovering it’s secrets in a series of brave, ambitious, and sometimes just plain unlikely experiments, to show you weather like you’ve never seen it before.

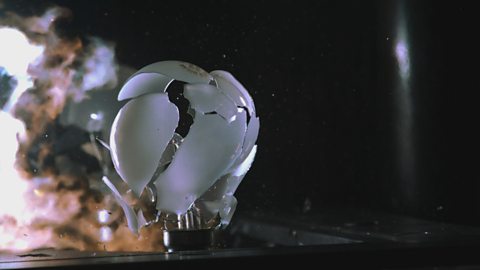

Tornadoes are the most powerful winds on earth. They move far faster than a normal wind - not in a straight line, but in the speed that they can spin. And it’s that spin that does the damage.

TO CAMERA: Look at it this way. If I’m spinning this bucket around my head, it’s not how fast I’m walking towards you that dictates how hard it will hit you when I get there. Even if I walk really quickly, that speed is irrelevant. It’s how fast I’m spinning the bucket that matters, and what’s in it to add to the weight.

And that’s how it is with a tornado. Debris does most of the damage - that’s the weight in the bucket. The most destructive force in the tornado itself is its spin - its rotational speed - which is why it’s remarkable that’s the part of a tornado we know least about.

NARRATION: To try and put that right, I’m visiting the distinctly un-tornado-like landscape of Ontario in Canada and one remarkable building. [ALARM SOUNDS AIR RUSHES.]

TO CAMERA: I’m going to do something a person wouldn’t normally do. I’m going in! It’s… Oh! I’m in! This is it. I’m in the eye of it. And, all I can say is yes - this feels as amazing as I suspect it looks. I’m in a tornado - it’s the most astonishing feeling. It’s dizzying. The world is roaring past spinning round me but I’m still. This is massively scaled down of course. A real one would be maybe 100 times bigger, and the wind moving four, five times faster. But nevertheless, you get a sense of … the relentless terrifying power ofone of these things in the wild!

NARRATION: This is the Wind Engineering Energy and Environment Research Institute - or Wind EEE for short. And it’s the only place on the planet capable of duplicating the real-life dynamics of a tornado. It does it by using 106 giant fans hidden behind the walls and ceiling of the world’s first hexagonal wind tunnel. The whole structure cost $23 million. Which makes it all the more delicate asking it’s boss - Professor Horia Hangan - for a little favour…

RICHARD: Just while we’re here, I’d really like to just have a little look at velocities - sort of that way - in tornadoes. Can we have an, I’m not going to say - experiment a bit with it? Do you mind if we make a bit of a mess? Not a massive mess. There might be … We’ll sweep up.

HORIA HANGAN: Mmm…

RICHARD: You won’t know we’ve been here. Everything will be gone.

HORIA: That’s fine. We can do a little bit of a mess here, so we are prepared to catch some stuff that you throw into it.

RICHARD: Might happen. Thank you.

HORIA: You’re welcome.

NARRATION: Good for him - he’s trusting us with his $23 million baby.

TO CAMERA: Right - plan. I want to look more into velocity, see how fast the wind is moving and if I introduce these ping-pong balls into our tornado, I can measure the speed. I’m going to feed them to it.

NARRATION: We think of tornadoes as sucking up everything in their path. Turns out, it’s not that easy. I retreat to the control room, where the professor and I spend the next four hours trying to get something - anything - to actually fly inside the tornado. With no luck. Then, one of the scientists finds these pink foam squares, which might just be light enough to do the trick.

TO CAMERA: If we can get those foam squares trapped in the tornado, and we can get them lifted up and spun round without being spat out, then we might be able to time how long it takes one to do a full lap.

HORIA: I’m going to start the fans.

RICHARD: You see? There it is.

HORIA: Looking good.

RICHARD: Yeah. Yeah!

RICHARD: Normally it’s impossible to judge a tornado’s speed near the ground, because of all the debris and objects in the way. But here we have a real chance. Time to turn on the tracking technology. The computer follows individual squares one after another. So, it can create an average speed from the different trajectories. And it works - according to the computer it’s spinning at a shade over 22 mph. A real tornado could be ten times faster than that, but this is still the first time any tornado has been measured this near the ground. If we could find a way to do this in the wild, then we might change our understanding of tornadoes forever.

Download/print a pdf of the video.

Richard Hammond explores the properties of a tornado that has been created in laboratory conditions.

He learns about how tornadoes cause damage – it's the speed of the spinning within the tornado, rather than the speed and direction of the whole tornado.

The main cause of damage in a tornado is from the debris carried by the phenomena. Richard visits a tornado wind tunnel at the WindEE Research Institute in order to demonstrate how the speed of rotation can be modelled within loose scientific conditions.

He considers the effects of tornadoes before demonstrating how the speed of a tornado alters through a cross-section, tackling the misconception that tornadoes 'suck up' everything in their path.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3

This short film provides discussion points around experiment design and measurement. How can modelling a tornado inside a laboratory help people living in the real world?

For example, it’s very difficult to measure the velocity of a tornado in the real world due to the debris being carried. Compare the speed of the lab tornado with the Beaufort Scale – what damage would be done? How could Richard have designed the experiment to be more effective with more accurate and reliable results?

You could stop the clip after the segment with the ping-pong balls and discuss how to make the experiment better - what material could be used? What properties would that material have?

Key Stage 4

This short film could be a good introduction or revision of the forces involved in a tornado such a Coriolis. Students can be asked how they would work out the velocity within a tornado – what data would they need?

Curriculum Notes

This short film could be used to teach geography and physics at KS3 and KS4 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and National 5 in Scotland.

At GCSE it appears in AQA, OCR A, EDEXCEL, EDUQAS, WJEC and CCEA, in SQA at National 5.

More from Richard Hammond's Wild Weather

How can you cool a drink using the sun? video

Richard Hammond uses a beach, a towel, water and a drink to demonstrate how evaporation can be used to cool liquid.

How does a thermal form? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates how thermals are formed through heat from the sun.

How does hail form? video

Richard Hammond explores the weather conditions that form hail.

How to see thunder. video

Richard Hammond visits Lightning Testing and Consultancy in Oxfordshire to take part in laboratory experiments that demonstrate the effect of thunder within controlled conditions.

How to use wind to forecast the weather. video

Richard Hammond demonstrates how we can forecast the weather simply by watching the way the wind effects the clouds.

What is the difference between rain and drizzle? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates a visual technique to distinguish between drizzle and rain.

What is wind? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates how wind is created due to differences in air pressure.

Why does water fall as rain? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates the effect of water on other physical objects.