Why does water fall as rain?

NARRATION: Wherever you live on the planet, weather shapes your world. Yet for most of us, how it works is a mystery. So, I’m going to strip weather back to basics - uncovering it’s secrets in a series of brave, ambitious and sometimes just plain unlikely experiments. To show you weather like you’ve never seen it before.

TO CAMERA: We talk about heavy rain, but water is heavy - very heavy.

NARRATION: To give us an idea of just how heavy, we’re going to take the annual rainfall for England’s rainiest place and put it … in this bucket.

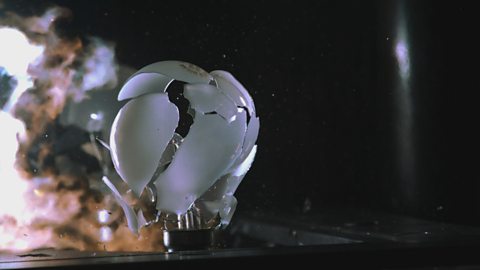

TO CAMERA: So, we have four cubic metres of water in the bucket - which amounts to four tonnes - at height. Then, beneath it, you’ll see we’ve found a car. For scientific purposes.

NARRATION: Let’s see just how much damage that amount of water can do. Hmm. Looks like rain… Yeah - pretty brutal. But I shouldn’t be surprised. Because the water actually weighed four times more than the car underneath it.

TO CAMERA: [INSPECTING THE CAR.] Oh, they’re going to notice! But it does prove the point. Water is really heavy. That’s just the annual rainfall for Borrowdale. Where I’ve been going on holiday all of my life. Explains something about it!

NARRATION: Luckily, this could never happen with real rain. To show you what I mean, I’m hard at work building a sandcastle. And Professor Jane Rickson, from Cranfield University, is filling a plastic bucket - from a pond.

RICHARD: There were always kids like you on the beach, weren’t there?

NARRATION; OK, so what’s all this about? Well, pour water on a sandcastle and you completely flatten it. No surprises there. But rain doesn’t fall from waist height. It falls from clouds that are at least 300 metres above the ground. And that makes all the difference. Let me show you, by building another sandcastle. I’m throwing the water off something … just a little bit higher.

TO CAMERA: Now obviously, this isn’t as high as a real cloud: they start at around 300 metres. This tower is 30, but it’s tall enough for what we want to do.

JANE RICKSON: OK, Richard, let it go! [WATER RELEASED TO WRONG AREA.] Idiot!

NARRATION: Yeah, wrong side. Let’s try it again. And so, another bucketful leaves the tower, but what arrives below … is rain.

RICHARD: So, why? Why is it if I throw the water from up there, you’d think it would smash it to bits even more but it’s still standing what’s the difference?

JANE: Well, what happens … as you were throwing that water down, air resistance the turbulence in the air, is overcoming the surface tension of that lump of water, breaking it into smaller drops.

NARRATION: As the water falls, it meets air resistance and the larger the lump of water the more resistance it experiences. That friction breaks the water up into smaller pieces, sometimes inflating the drops like parachutes, before blowing them apart. The further they fall, the smaller those drops become. Until, finally they’re so small that the air has little effect on them. If our digger had been just a few metres higher … then the car might well have survived.

Download/print a pdf of the video.

Richard Hammond demonstrates the effect of water on other physical objects.

Water weighs around one kilogram per litre. The annual rainfall of England's wettest place, Borrowdale in the Lake District, is placed into the bucket of a machine. This is then dropped onto a car, crushing it.

Richard then moves on to demonstrate the effect of air resistance on raindrops. He builds a series of sand castles at the base of a tower in Bristol. When water is dropped from waist height the sandcastle is crushed. When dropped from height (30 metres), the water has less effect. The effect of air resistance on water is therefore explained.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3

This short film provides a demonstration of water’s power and weight. Pause just before the bucket is tipped in order to ask your class to make predictions on what will happen to the car.

This provides a nice link to science / physics as well as geography. You could look up precipitation information for Borrowdale in the Lake District. Why doesn’t the rain crush us? Then play the Bristol part of the clip.

Key Stage 4

Students could explore various sources of information in order to produce an explanation of why Borrowdale is the wettest place in the UK, linked to relief rainfall and the rain shadow. What are the other climate variables there annually? Science students could talk about reliable experiment design.

Curriculum Notes

This topic appears in geography and physics at KS3 and KS4 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and National 5 in Scotland.

At GCSE it appears in AQA, OCR A, EDEXCEL, EDUQAS, WJEC and CCEA, in SQA at National 5.

More from Richard Hammond's Wild Weather

How can you cool a drink using the sun? video

Richard Hammond uses a beach, a towel, water and a drink to demonstrate how evaporation can be used to cool liquid.

How does a thermal form? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates how thermals are formed through heat from the sun.

How does hail form? video

Richard Hammond explores the weather conditions that form hail.

How to see thunder. video

Richard Hammond visits Lightning Testing and Consultancy in Oxfordshire to take part in laboratory experiments that demonstrate the effect of thunder within controlled conditions.

How to use wind to forecast the weather. video

Richard Hammond demonstrates how we can forecast the weather simply by watching the way the wind effects the clouds.

Inside a tornado. video

Richard Hammond explores the properties of a tornado that has been created in laboratory conditions.

What is the difference between rain and drizzle? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates a visual technique to distinguish between drizzle and rain.

What is wind? video

Richard Hammond demonstrates how wind is created due to differences in air pressure.