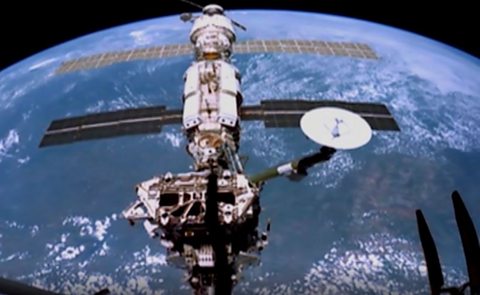

TIM PEAKE:Hi, I'm Tim Peake. I'm an astronaut based here at the European Space Agency, in Germany. And from December 2015 to June 2016, I spent 6 months orbiting Earth on the International Space Station.

TIM PEAKE:My experiences on the ISS have fuelled my belief that one day, in the not too distant future, we will be able to send people on the long journey to our nearest planetary neighbour Mars.

TIM PEAKE:Scientists have already sent a relatively small explorer robot, called Curiosity, to the red planet back in 2013, but when people eventually go over there one of the biggest challenges will be the actual landing process.

TIM PEAKE:So with that in mind, let's meet the NASA scientists and look at the physics that could make it work.

NARRATOR:'After travelling for over 8 months 'and across 56 million km of space, 'you're finally arriving… 'at the planet Mars. 'Now comes the greatest engineering challenge of the whole mission. 'Landing.

NARRATOR:'Dr. Adam Steltzner 'has been set the task of working out how it'll be done. 'He masterminded the audacious landing of the Curiosity Rover 'on Mars in 2012.'

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:I have tried… to describe that, many times, and I fall short. And I fall short because it pegged my emotion level. You know I have a meter, it just buried the needle. But my career is not over, I'm going to try and make something better.

NARRATOR:'But landing a human crew is a different matter entirely.'

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:'Landing Curiosity, a ton, biggest thing we've landed on Mars to date. 'A challenge but not nearly as much of a challenge as landing humans.'

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:Humans are sensitive, they're delicate, they don't like a lot of G's, they like to carry water with them, they're heavy. So we think that landing humans might be something like 40 metric tons, or maybe more.

NARRATOR:'Once again with a spacecraft carrying humans, 'it's the bigger size that raises challenges.'

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:There's this interesting pit of physics that occurs as you scale up things. Imagine scaling up a drop of water. As it gets small or big, its weight goes up with the size of it. Cubed, raised to the third power.

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:But its aerodynamic drag gets larger based on its area, which is its diameter squared. What that means is, the bigger this self-similar thing gets, the more easily it falls. Same thing happens with spacecraft.

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:So if you think about Curiosity, she came in going very, very fast, slowing down, slowing down and eventually making contact with the surface.

NARRATOR:'The smaller size of Curiosity, 'meant that it was successfully slowed 'by aerodynamic drag as it fell. 'But scaling up the size for a human lander 'changes the physics of landing radically.'

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:I've got this self-similar shape. I'm going to not put Curiosity on the surface, but I'm going to put two Curiosities. Okay. Three, four, five, getting a little challenging. 40 - now all of a sudden I can't fly that shape.

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:It's the same shape it was before, it's packed at the same densities of spacecraft but now it ends up flying a trajectory… That intersects the surface of Mars when it's moving Mach 20. Not good.

1900:04:19:01 00:04:40:06DR. ADAM STELTZNER:Perhaps to get really big things to the surface of Mars, what we need to do is… We need to make our shape like this, which regular rockets look like, but when we come flying in we don't put the pointy end in or the back end in we come in sideways.

NARRATOR:'By coming in sideways, 'the drag on the spacecraft is increased significantly. 'Slowing the rocket from hypersonic to supersonic. 'To slow it down further 'you need something else to push against the gravity of Mars.'

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:It's called supersonic retropropulsion. Imagine motorbiking with your mouth open at 60mph. It's whoa, it fills your mouth with air, and it's actually sometimes hard to breathe out against it Well that is the challenge of supersonic retropropulsion.

DR. ADAM STELTZNER:You're going to light a rocket off, into the flow, but it's going to be supersonic flow. Well NASA's working on that. And it's like they take those rockets from a supersonic condition, all the way down to the surface.

TIM PEAKE:Got that? As you're approaching landing, you fire the rockets in the direction of the surface to try and counter the force of Mars' gravity. A challenge but then so is everything to do with space exploration.

This short film, first published in 2018, is for teachers and review is recommended before use in class.

Tim Peake introduces the Physics behind a human visit to Mars.

After a journey of 8 months the biggest engineering challenge will be landing.

Adam Steltzner is the engineer from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory working out how it can be done.

He masterminded the landing of the 1000kg Curiosity probe, but a human lander would be around 40,000kg.

This is significantly harder as the mass scales with the length cubed but the drag scales with the length squared.

This means that in the Martian atmosphere the drag will be too small to stop the human lander.

New ideas will be needed such as firing a rocket towards the surface of Mars.

Teacher Notes

Key Stage 3/4

Students could investigate the effect of drag in the classroom.

They could time how long it takes objects to fall a fixed distance.

The objects could have a constant surface area and increase in mass or have a constant mass but increase in surface area.

Sheets of paper or small paper cake cases are suitable in air or ball bearings in a measuring cylinder of treacle or vegetable oil.

Students could investigate the relationship between the side length and surface area of a face or volume of a cube as the side length increases.

Calculations could be performed, graphs drawn and conclusions made.

GCSE/Higher

Students could investigate the effect of drag in the classroom.

Students could be set a challenge to consider what may affect the terminal velocity of an object falling in air.

Students could use dimensional analysis to determine the exact form of the equation and then plan an investigation to check their equation.

Students could then use appropriate log graphs to verify the powers of area and mass.

Curriculum Notes

This clip will be relevant for teaching Physics/Science at KS3 and KS4/GCSE in England Wales and Northern Ireland.

Also at 3rd Level, National 4/National 5 and Higher in Scotland, and Cambridge IGCSE Physics.

More from the series Curriculum Collections: Physics

A scale model of the solar system. video

Dallas Campbell shows an orrery – a mechanical model of the solar system.

Centripetal force - explained. video

Tim Peake introduces Yan Wong who explains centripetal force using a cup of water on a tray hanging from a string.

Days, Years and Seasons on Earth. video

Professor Brian Cox explains the seasons on Earth and the orbital periods of planets in the solar system.

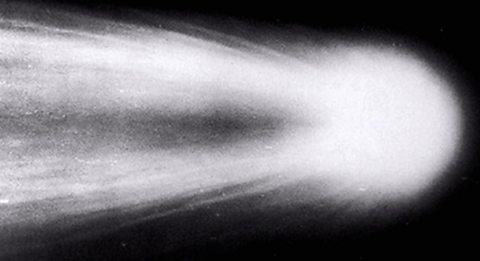

How Halley’s Comet inspired Newton’s Law of Gravity. video

Simon Shaper explains how Newton’s Law of Gravitation originated from observations of Halley’s Comet in 1680.

The Origin of the Northern and Southern Lights. video

Helen Czerski explains the origin of the Northern and Southern Lights.

Launching satellites into orbit. video

Tim Peake introduces Maggie Aderin-Pocock who explains how satellites are launched into orbit around the Earth.