Why are scientists so intrigued by the food matrix?

By Sue Quinn

For decades, scientists have focussed on the types and amounts of specific nutrients in a food to assess how good it is for our health. But emerging research suggests there are other ways to gauge a food’s nutritional value in addition to its nutrients. It’s a concept known as ‘the food matrix’.

The term refers to a food’s physical structure, the way the molecules inside it interact, and how this interplay affects the way we digest and absorb nutrients. It’s thought the food matrix better reflects a food’s potential health benefits and contribution to our wellbeing than simply considering its nutrient content alone.

Understanding the food matrix

To understand the concept, it’s useful to think about food as ‘tasty structures’ that contain the molecules we need for energy, and to create and replace tissues, says José Miguel Aguilera, emeritus professor of chemical and food engineering at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

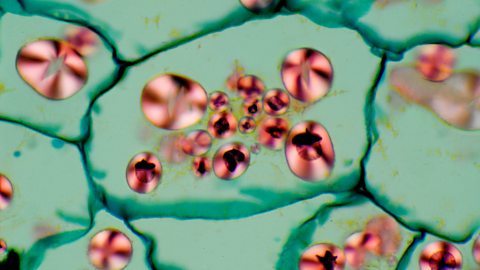

“Molecules come embedded by nature in often complex functional microstructures that we cannot see, for example, inside cells as starch granules, or covered by a biological membrane as fat globules in milk,” he says. “During industrial food processing or cooking, we create new microstructures that further combine and hide food molecules due to mixing, shearing and heating. In food technology we call these special microstructural arrangements containing food molecules a food matrix.”

Examples of the matrix

Dr Sarah Berry, a nutritional scientist at King’s College London, says almonds are a good example of how changing a food’s matrix can alter its potential benefits to our health. Whole almonds and ground almonds are nutritionally identical according to information on the packet. However, this is incorrect, as the nutrition data doesn’t consider the almonds’ different structures, Dr Berry says.

“Nuts have millions of little cells with cell walls [which is the fibre], and within those cell walls are fat globules,” she says. “If I finely grind the nuts, I'm breaking the cell walls and the fat bursts out. But when you consume the whole nuts, the matrix keeps the fat within the cell wall, which is not easily digestible.”

Research has shown that approximately 30% fewer calories are absorbed from whole nuts than ground nuts, because the undigested fibre and fat passes through the body and is excreted. Some fat-soluble vitamins are lost in this process, but there are benefits to eating the nuts whole. They’re less calorific than many people realise, which is an advantage if you are watching your weight, and they feed your gut microbes, Dr Berry says.

“They feast on all the fat, fibre and other nutrients you haven’t absorbed, and improve your microbiome composition, which we know is really important for health,” she says.

Related stories

The dairy matrix

Although research into the food matrix is still in its infancy, the concept is relatively well understood in dairy products, says Ian Givens, a professor of food chain nutrition at Reading University. Studies show that eating butter causes a rise in blood cholesterol, especially LDL or the ‘bad’ kind. However, eating hard cheese that contains the same amount of fat and has a similar fatty acid composition as butter can cause a much smaller rise in blood cholesterol levels, no rise at all or even a fall.

This is partly due to the physical differences in the matrices of butter and cheese. The protein structure of cheese protects the fat from being absorbed, which doesn’t happen with butter. The interaction of nutrients also plays a part in the dairy matrix. Cheese, which is richer in calcium than butter, reacts with fatty acids to form substances that are difficult for the body to absorb. Calcium, phosphorous and bile acids also combine in a way that can’t be absorbed, which results in the liver drawing cholesterol from the blood, which can reduce blood cholesterol levels.

“The emerging science is saying there are factors other than the protein, fat and carbohydrate content of foods that affect its nutritive value and potentially, its health value,” Prof Givens says.

Ultra-processed foods

Of course, disrupting a food’s matrix isn’t necessarily bad. Chewing and cooking food changes its structure, processes that have been essential for human development. “Changing structures by processing made us humans,” Prof Aguilera says. “Our brains would not have acquired the energy to function and some proteins we needed for tissue building and replacement would have remained only partly digestible had we not discovered fire. Cooking, a form of changing and creating food structures, also contributes to our mental health and social health.”

Some forms of food processing, such as canning, preserving, and fermenting (in gut-healthy products like kimchi and sauerkraut) have clear health benefits. But ultra-processing can alter a food’s matrix in potentially harmful ways, Dr Berry says. Moderately processed coarse oats, for example, are digested by the body slowly. But finely ground quick-cook oats - nutritionally identical to coarse oats – are rapidly absorbed. This explains why breakfast cereals made with fine oats often don’t fill you up for long and can lead to spikes and dips in blood glucose levels. Over time, such spikes can lead to inflammation, which is linked to a range of chronic health conditions including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and obesity, and dips can lead to hunger and excess calorie intake.

“By keeping the oats close to the original matrix, which is how we would have consumed them a hundred years ago, you’re getting all the nutrients but at a slower rate than the fine oats,” Dr Berry says. “Nutritionally, coarse oats and ultra-processed oats might be the same, but the way they behave is very different and that’s to do with the processing.”

Ultra-processed foods not only have their natural matrix altered, but other ingredients are added including sugar, salt, fat, and artificial colours, and preservatives. “They tend to be highly refined ingredients, fast digestible carbohydrates and other kind of additives,” Dr Berry says. “There's evidence now emerging these may have unfavourable effects including on the microbiome.”

Benefits of food matrix research

As their understanding of the subject deepens, nutritional scientists hope to develop different ways of altering a food’s matrix that might enhance human health.

Dr Berry and her colleagues at King’s are researching ways to unlock the iron ‘trapped’ in wheat by micro-milling the aleurone, the outer layer, where it resides. This form of iron is much more readily absorbed by the body than that which is currently used to fortify flour. Dr Berry says one day it might be possible to fortify flour with the iron retrieved from micro-milling wheat instead, which could help tackle the significant global problem of anaemia caused by iron deficiency.

Prof Aguilera says that by harnessing their knowledge of the food matrix, nutritional scientists will eventually be able to redesign some foods to protect nutrients and target them to perform specific functions. For example, the elderly face significant physical barriers to eating and enjoying food and have particular nutritional requirements. “We can now develop food matrices that are soft and resemble and taste like actual foods, that are safe to swallow, full of flavour and have the requisite nutrients for a healthier and more enjoyable aging,” he says.

Food labelling

If a food’s matrix should be considered when gauging its potential health benefits, does this make nutrition labels less meaningful? “The food matrix concept is in contrast to the traditional ‘simple’ view, which says you just need a set of nutrient requirements and a database of nutritive values,” Prof Givens says. “We know that nutritive value can vary within a food and data sets will not generally account for that.”

But not enough is known about the food matrix to replace the existing nutrition labelling system. “I think the quantification of matrix effects is at a very early stage and there is not really enough good data yet,” Prof Givens says. “Matrix effects are recognised but really not quantified. One of the biggest challenges to the world of dietetics in coming years will be how to build matrix effects into diet formulation. I think it will be a long time before that happens.”

In the meantime, Dr Berry suggests not to focus too much on the nutrition and calorie information on food packets. “Think about the food matrix,” she says. “Is your food in its original structure?” Generally, that means eating whole foods, or foods that have been minimally or moderately processed where possible. “Generally, if we follow that rule of thumb, we're doing well.”

But we also need to be pragmatic. Eating whole fruit is better for us than consuming it in a smoothie, because you change the fruit’s matrix, particularly the fibre structure, by blitzing it in a blender. “But it’s preferable to have a smoothie than no fruit at all,” Dr Berry says. “If a food is too healthy to be enjoyed, it just isn’t healthy at all.”

This story was published in January 2022.