Journalists and academics: trade your ‘fortresses’ for practical partnership

Matthew Eltringham

is editor of the BBC College of Journalism website. Twitter: @mattsays

Perhaps that’s why the current relationship between academia and journalism is like two hedgehogs mating - prickly and stand-offish.

However, despite their differences, the two cultural institutions are facing similar challenges to the way they operate.

Old-style ‘fortress journalism’ has been under relentless attack for some years from the changing digital and social frontlines. No longer can the white, male journalist sit in his ivory-towered newsroom holding onto ‘The News’ until six o’clock, when a grateful public will listen quietly and respectfully to his words of wisdom.

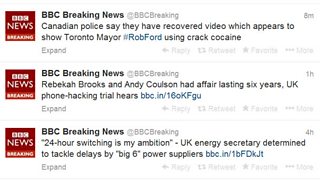

That ‘The News’ now appears first on Twitter has already become a truism. The Arab Spring and many, many other stories are testament to the power and importance of social media. That is why the BBC has focused substantial resources on engaging with social media to both source and share our journalism. We embrace it or risk becoming irrelevant at best, redundant at worst.

Fortress BBC, 1930s style

Why wait 18 months to publish your research in a fusty old journal when you can blog about it instantly?

It’s easy to make cheap jibes about dumbing down and hide behind the walls of fortress academia, in the same way that I used to hide behind the walls of fortress journalism - I am telling you THE NEWS and you need to listen to me because I am a BBC journalist.

But if we succumb to that temptation we risk throwing away one of the key values that has to define our new relationship - one of relevance. These digital and social forces are the ones that are shaping our world now. We need to understand them AND use them in order to continue to connect to both an academic audience and a journalistic one.

This challenge was really brought home to me when I spoke to an academic colleague who is at the start of his academic career. He has just published his doctoral thesis after three years of hard grind - researching digital media and reporting conflict, seen particularly through the eyes of the BBC’s coverage of war and terrorism.

Throughout his research he blogged, and one of the most rewarding responses he has had was not to the many thousands of words of his thesis but to something that came out of his research that he posted to the Frontline Club’s blog, unpicking the myth of the Moldova ‘Twitter revolution’.

My colleague’s profound satisfaction came in the knowledge that his work had made a practical difference to the journalism he was studying; not that he had been cited in some learned journal.

The impact of his blogging meant he thought seriously about publishing the entire thesis online in a blogging format rather than a conventional one. But, because he’s looking to pursue an academic career, he felt had little real option and Routledge published his work a few months ago.

He is convinced that his blogging hasn’t helped his academic job prospects - and has possibly hindered them.

So, if impact is measured simply in the traditional academic sense of citations, that looks like a pretty tough game to play. I’m not going to argue that we should never engage in, fund or support purely academic work into journalism - of course we should. But don’t expect me or my journalist colleagues to be tremendously interested in it. And to be brutally honest, looking at these tweets, it’s not entirely clear how much other academics are either.

We have a lot of requests from academics across the UK to partner or help them in their research. We are nice, helpful people, but the first question we ask when assessing whether or not to agree to work with an academic is ‘what’s in it for me?’

We reject the overwhelming majority.

The journalist Eric Newton wrote a very provocative blog for the Knight Foundation questioning the value of academic research in journalism. It quotes a senior journalism teacher: “There are three categories of research these days: 1. Who cares? 2. No shit! 3. I don’t have any idea what you are talking about. To be generous, perhaps we should add a category: 4. Needs more work, but there might be something there.”

Needless to say there were dissenters.

So what should be the foundation of a fruitful - and genuine - partnership between academics and journalists? From where I stand it has to be relevant, practical and useful to both journalists and academics.

Perhaps I can offer two examples of the kind of work I am talking about. The first was produced by Claire Wardle, who was an academic at Cardiff University’s Journalism of School. Claire left the academic world for journalism, where she now works closely with a number of media organisations as a consultant and trainer.

The second was produced by Emily Bell, who was director of digital content at the Guardian newspaper and is now professor of professional practice and director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University.

They both have what I would call ‘crossover appeal’. They understand the interests, demands and pressures of both academia and journalism.

Claire’s work, in conjunction with her colleague Andy Williams back in 2007-08, was the first proper look at the way user-generated content (UGC) was affecting journalism and journalists. UGC: Understanding its impact upon contributors, non-contributors and the BBCwas co-funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the BBC.

The research involved six different methodologies: 10 weeks of observation at different newsrooms across the BBC; a nationally representative Ipsos MORI survey of 944 people; an online survey of 695 BBC website contributors; 12 focus groups with 100 people; 115 interviews with BBC journalists; 10 interviews with senior managers and BBC executives; and analysis of 105 hours of news output from 13 national and regional TV and radio programmes (and associated websites).

It remains a seminal piece of work on the subject, providing insight into what people thought about participation in the news process, what kinds of people did it and why.

It provided significant signposts for the BBC in its foray into the use of UGC. I was then running a small experimental team in the BBC’s network newsroom called the UGC Hub. That is now integral to our news operation and has become a significant operation of 20 journalists whose job it is to find, verify and then share across the news operation key bits of user-generated content that we incorporate into daily output.

In 2008, Claire wrote: “For all the excitement about UGC democratising news, the vast majority of the population have never contributed material. There are significant barriers to participation and news organisations should be thinking about ways of minimising those barriers to broaden the range of views and opinions included in their news output.”

In it the authors examine the present state of US journalism and what can be learnt from it - in a way that might offer clues and insight into the new possibilities for journalism. They look at the news ecosystem, news organisation and business models.

“Merely bolting on a few new techniques will not be enough to adapt to the ever changing ecosystem; taking advantage of access to individuals, crowds and machines will mean changing organisational structure.”

They add: “We recognise that many existing organisations will regard these recommendations as anathema.”

These two pieces of work both tackle the key issues that are right now challenging journalism, journalists and the industry built on them. They help journalists understand the fundamental changes that are being driven by the inexorable and inexhaustible rise of the digital world and the social web.

They therefore help us find a route through to the ‘next world’. And they are - frankly - written in a language and style that we understand; or perhaps more accurately one that we are prepared to put up with.

They retain academic worth and credibility. They explain why a genuine partnership between journalists and academics is important, because they help us understand the issues that are disrupting our industry and threaten to unseat us all.

They have real impact in the real world. They are practical, relevant and useful.

This is an edited version of a speech Matthew Eltringham gave at the recent Jonkoping University conference in Sweden, ‘Towards a Practice-based Media and Journalism Research’. In part two of the blog, he urges academics to focus on skills that will have the most impact on the way the next generation of journalists will work.

Arab Spring protest photo is by Mosaab Elshamy, who began documenting the upheavals in Egypt as a citizen journalist.

Why journalism education faces a worrisome future

Journalism schools need to adapt or risk becoming irrelevant