News start-up will stick with stories after the press pack has left

Natalia Antelava

is a journalist and co-founder of Coda Story

Former BBC correspondent Natalia Antelava is the co-founder of Coda Story, a journalism start-up based in New York that wants to let reporters stay on a story after the mainstream media have moved on.

Do you ever feel that one minute you are bombarded with news from one place – Paris, Greece, Iraq - and then it drops off the radar. What happens to crises after they disappear from the news? They don’t end. In fact, often the most important things happen after journalists leave, sometimes precisely because they have left.

I remember the moment I thought something had to change about the way journalists cover crises. It was three years ago in the bleak departure lounge of Sana’a International airport. I had spent six weeks reporting on Yemen’s violent anti-government uprising for the BBC. I was exhausted and looking forward to getting out. But leaving also felt deeply wrong.

As I walked towards the gate, I thought of Yemen's uncertain future, the people I was leaving behind and their stories that would now go untold. I had another assignment waiting, and it’s not that my editors didn’t care about Yemen; but with resources scarce and other stories fighting for their attention, the decision had been made not to replace me. I knew that without a reporter pushing from the ground, Yemen would disappear from the editorial agenda.

I had experienced it before: in Burma, in Uzbekistan, in Iraq and many other places where I had parachuted in, either on my own or as part of a team of international journalists. In the news business, we always descend on places when big events happen and then leave just as suddenly, pulled out by our own circumstances rather than because the story has come to an end. The result? Gaping holes in public understanding of the crises that are shaping our world.

After my trip to Yemen I reached out to several colleagues and together with the American magazine writer Ilan Greenberg and then Beirut-based Financial Times reporter Abigail Fielding-Smith, we embarked on a mission to figure out a model that would allow journalists to cover crises in a more meaningful way.

Abbie Fielding-Smith and Method Inc designer Andras Oravecz working on Coda

We Skyped between assignments, met up in different cities and brought others - technologists and veteran reporters, designers and editors - into the conversation. We believed that many consumers and producers of news shared our frustrations, but we also learned that lack of focus and resources were only part of the problem.

The bigger issue was that journalism as we know it is simply not designed to stay on a story. Traditionally, journalism has always used disposable platforms. Think about it: you read a newspaper, you throw it out; you watch a TV piece, and you never see it again. That’s why each time a story has to be told from scratch, repeating all the basics with only an update on the top. The internet has changed that by infinitely extending the shelf life of stories, but the media business is only beginning to rethink the potential this has for storytelling. Most of news industry continues to use the internet as a bottomless pit for updates.

We realised that in order to stay on the story we weren’t just talking about continuing to produce coverage when others had left. We had to do something more fundamental: to move away from news as a constant stream of incrementally-updated articles and reimagine a news platform.

That’s how we came up with our plans for Coda Story, a single subject crisis reporting platform. The formula is simple: we deploy like everyone else after a crisis, but we go in with a long-lens view. Our team of international and local journalists will stay on a single story for up to a year, covering it from many different angles. Our platform has been designed to show individual stories – whether photo, video or text - in the larger context of events.

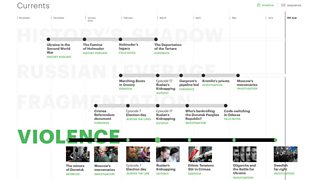

Coda's 'Currents' design tool - to show both individual stories and wider context at the same time

So how will that work in practice? In a few weeks’ time, we’ll find out as we embark on a three month-long pilot. Its subject is the crisis of gay rights in the former Soviet Union. From the Baltic to Central Asia the letters LGBT are no longer just an expression of identity: they are a rallying cry, either as a fundamental benchmark of tolerance or as a hate phrase defining a threat to tradition. Through despatches, video and photography we will tell how and why the crisis of gay rights pits the Kremlin against the West, both reflecting and feeding the wider geopolitical story, whether in Syria, Ukraine or in Russia’s response to the dramatic fall in oil prices.

Coda has non-profit status, but we are working to develop a range of revenue sources, from sponsored advertising to platform licensing and premium subscription service, to name just a few. The revenue will pay for Coda journalism and ensure its independence.

We have already received a grant from a charitable foundation to get the pilot off the ground and, to complete it, we have now launched a crowd-funding campaign on Indiegogo. You’ll be able to see the pilot project as it develops on our website.