Freelance journalists in Italy protest over minimum wage ruling

Alessia Cerantola

is a multimedia journalist at IRPI @aisselax

The discontent burst into flames with a street protest in Rome on 8 July, along with the launch of a Twitter attack under the hashtag #stopfnsi. In an online petition on Change.org, journalists asked for the withdrawal of the law and the resignation of the union's president. The organisation Youth Press Italia announced the cancellation of this year's Youth Media Days, a popular annual festival dedicated to young journalists in Naples. But without success.

The new law called “fair salary” (equo compenso) establishes a minimum wage for radio, video, print and web journalists who are members of the ODG but work without regular contracts. It states, for example, that a minimum of 144 articles of at least 1,600 characters each, written during the course of one year for the same daily newspaper, should be paid a total gross amount of no less than 3,000 euros (250 per month, about 20 euros per piece). Photos and videos provided with the story might increase the amount by between 30% and 50%. A minimum of six stories for a single local radio and TV station would be valued at no less than 3,000 euros per year. If the minimum is not reached, the rate is not necessarily applied. Finally, it specifies that journalists have to cover all their own costs in relation to the reporting process.

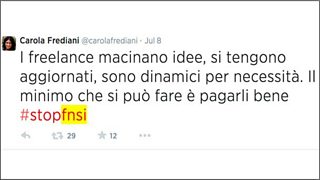

Tweet by Italian journalist Carola Frediani.

In a country where the annual income is nearly 29,000 euros, self-employed journalists, who according to a LSDI survey account for 60% of journalists in Italy, consider the rates outrageously low. Moreover, they are afraid that editors/publishers will interpret this not as a minimum rate but a suggested or fixed rate.

“It has legalised the practice of low rates, as has already happened before,” said Massimo Romano, a 32-year-old journalist who has been working for seven years as a freelancer for a local TV station. Producing five stories per month, he now earns around 600 to 700 euros monthly. But he fears that the law could reduce his salary.

“To be honest, the term ‘fair salary’ is not correct,” said Stefano Tallia from the FNSI. “We should better specify that this is just a minimum. The final price should be fixed by the journalists based on their skills, after talking with the editors.”

According to the contract, journalists can negotiate the price for longer or more complex pieces. But the reality is much worse. In some cases haggling over the price of a story written from a war zone, or even a local investigation about organised crime, can be harder than the reporting phase itself. A year ago a correspondent from Gaza denounced the same “fair” 20 euro rate for working as a freelancer for some national Italian newspapers.

Some staff journalists joined the protest backing the cause of disadvantaged journalists. “The new conditions exploit young journalists, chaining them to a desk until they are old, not providing them with the means to travel and give us insights from abroad, which are important for the future of the country,” commented Fiammetta Cucurnia, who has for many years worked as a correspondent from Russia for La Repubblica. “But for newspapers today what is important is only what is cheaper, not necessarily better.”

Despite the ailing market in Italy, the job of the journalist is still so highly sought after and idealised that many people are even willing to work for free or for an insultingly low income of just a few euros per piece. They tolerate an extremely unfair situation in the hope that they will one day be employed by that same/a media organisation.

What is clear is that trying to make a living exclusively as a journalist is an uphill struggle. Many have resigned themselves to doing other jobs to finance their journalism career, creating a mixed professional identity. In a Facebook discussion commenting on the law, Laura Silvia Battaglia, an experienced freelance journalist covering conflict areas in the Middle East, wrote: “I don't feel ashamed of the fact that I have worked at a sushi bar to earn the money for a three-month freelancing job abroad."

Others have started working on multimedia projects, teaming up with colleagues in similar situations to create media start-ups. A growing number of people think the only solution is reporting for foreign media to receive in order to better pay.

Beyond these economic issues, the substance of the contract, and the value given to the job of the journalist, raise concern about the future of information in Italy. Putting a price on, or, rather, putting a low price on articles by number, risks favouring quantity over quality.

Also, a law that fixes prices is not enough to stop editors from using other cheaper kinds of contract, argues journalist Davide de Luca in his blog. “It would be necessary to put a policeman in each newsroom.”

After the "Berlusconisation" of the media and mafia death threats, underpaid and exploitable reporters put the freedom of the press in Italy at risk.