Quick version

Irish Catholic migration to Scotland occurred in waves:

- early waves of Irish Catholic migration was temporary

- permanent, large-scale settlement began with the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-49

Irish Catholic migrants in Scotland were generally unskilled and took low paid work in mills, factories and mines. As such Irish migrants often faced discrimination in Scotland:

- they often spoke only Irish Gaelic

- they practiced a different religious faith to the largely Protestant Scots

- they tended to have poorer living conditions

Long-term settlement of Irish Catholics had a lasting legacy in Scottish society and culture:

- Irish Catholic communities had to raise money to fund schooling for their children

- political groups supporting Irish independence from Britain became popular in Scottish cities with large Irish Catholic-descended populations

- sports clubs set up to support Catholic communities – such as Celtic and Hibernian football clubs – made a lasting contribution to Scottish society

Learn in more depth

Earlier migration saw smaller numbers of Irish migrants settle in Scotland. These were largely temporary workers – such as farm workers paid to help harvest Scottish crops – who stayed in Scotland after the seasonal employment ended.

These migrants soon became assimilated into the wider Scottish population. Irish surnames such as O'Neil were changed to McNeil, for example.

Later mass migration after the Irish Potato Famine (1845-1849) saw larger numbers of Irish Catholic migrants settle in Scotland and establish permanent communities with their own distinct identities.

Employment for Irish Catholics

Image source, ALAMY/Hazel McAllister

Image source, ALAMY/Hazel McAllister The majority of Irish workers arriving in Scotland during the 1800s were Catholic. The migration of Irish Protestants to Scotland in sizeable numbers happened later in the 1800s.

The earlier waves of Catholic worker were largely unskilled and took up low paid work in the factories, mines and mills of the Central Belt and southern Scotland. Many of the Irish immigrants were poorly educated and some spoke only Gaelic. This could be a barrier to finding better paid work.

The arrival of a workforce that would work for lower pay was seen as a threat to Scottish workers. Many believed that Irish workers would force down wages for them.

There was also a fear that Irish workers would be used as strike-breakers to replace Scottish workers who were fighting for better wages or conditions.

This fear of competition for jobs led to open discrimination against Irish Catholic migrants in Scotland.

Image source, ALAMY/Hazel McAllister

Image source, ALAMY/Hazel McAllister Education

Education for the children of Irish migrants continued to be a problem.

During the 1800s, there was little provision for educating the children of workers. There were few schools and attendance at school was not compulsory.

Catholic schools initially received no state funding and relied solely upon voluntary contributions to survive. They were also bound by state legislation that prohibited teachers from instructing in the Catholic faith and Protestant bibles were to be used in all religious lessons.

1872 Education Act

The 1872 Education Act made education compulsory for all children. While this made education available to children from poorer backgrounds, it increase the burden of financing the Catholic schools.

Major fundraising campaigns, fairs and concerts were organised in aid of school funds. All of these enhanced the community pride and identity enormously and was a remarkable achievement for a largely poor community. By 1876 there were 192 institutions serving nearly 25,000 students.

However, despite these successes was not enough to prevent Catholic schools lagging behind the state schools in terms of buildings, resources and teaching staff.

The Education (Scotland) Act 1918

Following the end of the WW1, The Education (Scotland) Act 1918 brought Catholic schools into the state system.

This relieved many of the poorest communities of the burden of financing their own school systems. For agreeing to this transfer the Catholic schools were granted full rights to allow priests to take active involvement in their schools as well as the right to appoint teachers approved by the church.

This change provoked some protest from some Protestant communities who complained about “Rome on the rates”.

The 1918 Education Act helped to improve the education levels of the Scots-Irish, allowing them access to higher education and better jobs. This quickened the process of assimilation into wider Scottish society.

Housing for Irish Catholics

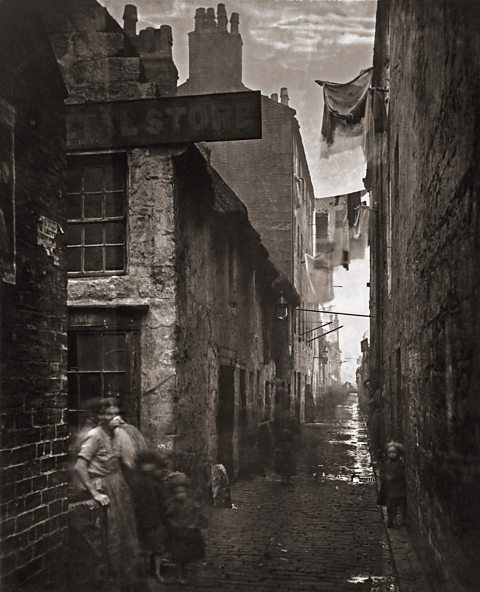

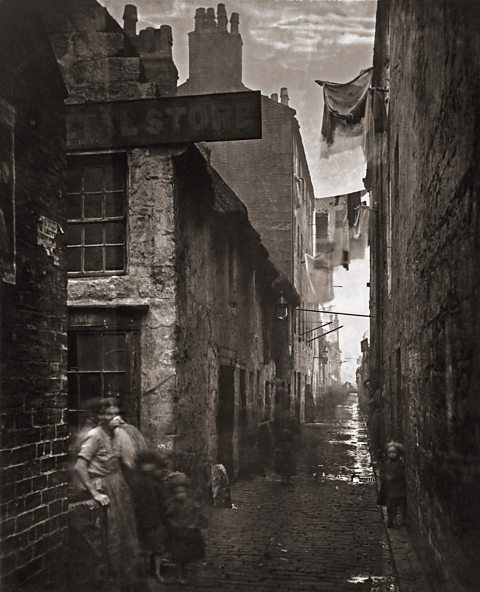

Image source, Universal History Archive / Getty

Image source, Universal History Archive / Getty While the mostly Protestant skilled Irish workers could generally expect better quality housing, most unskilled Irish Catholic workers found themselves in far less favourable accommodation.

Overcrowding was common and large families were forced to live in small spaces – often with up to 12 people in one ‘house’. Many people lived in ‘single ends’ (houses consisting of one room only).

Scottish tenements in poorer areas of cities such as Glasgow and Dundee typically lacked washing facilities and toilets. These were usually shared and located in separate buildings and water was collected from a shared standpipe on the street.

Disease spread due to the lack of sanitation and overcrowding. Water was frequently contaminated with sewage and refuse and as a result, cholera was common. Communicable diseases such as typhusAn infectious disease spread by lice. It causes a fever and can be fatal. and tuberculosisAn infectious disease that affects the lungs. It causes breathing difficulties and can be fatal. spread quickly as people lived so close together and fresh air was lacking.

Middens (heaps of refuse) were located behind the houses – they created foul air and attracted rats.

Image source, Universal History Archive / Getty

Image source, Universal History Archive / Getty Religion

Image source, ALAMY/John Peter Photography

Image source, ALAMY/John Peter PhotographyWhile there were many churches catering for Scottish Protestants, there were comparably few churches to cater to the Irish Catholics. St Andrew's Church, built in 1816, was the first Catholic church built in Glasgow since the Reformation.

In 1836, there was only one priest for every 10,000 Catholics. Due to a lack of Catholic priests and churches in Scotland, it was difficult for Catholics to practice their faith.

Catholic services for important events such as marriages, births, and deaths were difficult to obtain. As a result, many of the early wave of Irish Catholic migrants lost their faith and assimilated into Protestant Scottish culture.

In the early period intermarriage with Protestant Scots was relatively common as it was seen as the easiest way to assimilate into Scottish society.

Intermarriage was made more difficult by the Vatican's rigorous Ne Temere decree of 1908. Meaning "not rashly", the Ne Temere decree meant that priests could refuse to perform mixed marriages between Catholics and Protestants.

By 1878, the number of priests in Glasgow had risen to 134. By 1902, the number of priests increased to 234 and a total of 44 new chapels were built.

Catholic priests at this time also began to forge much stronger links with their community in Scotland and there were also Catholic charitable organisations, such as the St Vincent de Paul Society, that were established to help the poor.

Image source, ALAMY/John Peter Photography

Image source, ALAMY/John Peter PhotographyScottish culture and society

Irish Catholics and their descendants went on to have a profound effect on Scottish society and culture.

Politics

In Ireland, by the later decades of the 1800s, there was growing sense of Irish cultural identity that developed into a political movement.

Organisations such as the Home Rule Movement and Sinn Féin were established to campaign for Ireland’s political separation from Britain.

Outside of Ireland, there was popular support for this cause in areas that were home to large, settled populations of Irish Catholic migrants. This was the case in Scottish cities with sizable communities with Irish Catholics, such as Glasgow.

By 1920, there were 80 Sinn Féin clubs in Scotland, all supporting Irish nationalism.

Irish immigrants and their descendants had an impact on Scottish politics. The Irish were important in the Scottish Trade Union movement and the development of the Labour Party in Scotland. The Irish community produced important Labour political leaders such as John Wheatley and James Connolly.

Football and Irish culture

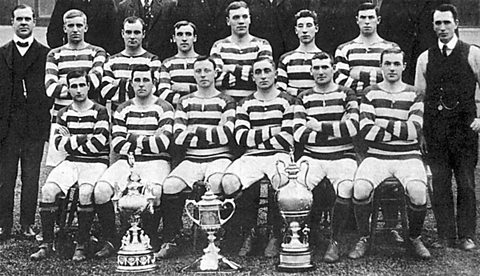

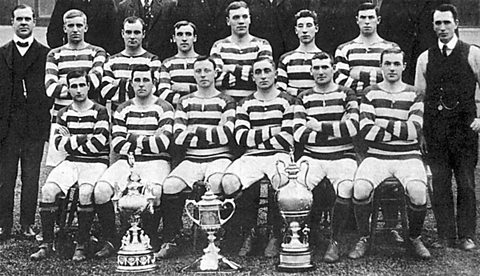

Image source, ALAMY/Archive PL

Image source, ALAMY/Archive PLOne of the most visible contributions to Scottish culture was seen in football.

Edinburgh's Hibernian Football Club (founded in 1875) became the first Catholic football team in Scotland. This was quickly followed by teams in many of the major towns.

In Dundee, a football club catering for the city's Irish Catholic community called Dundee Harp briefly existed (formed in 1879 before going out of business in 1894). The better known club Dundee United was formed in 1909. Originally named Dundee Hibernian, it was also formed by Irish workers in the city's industries.

Celtic Football Club was first proposed by an Irish priest called Brother Walfrid as a way to raise money to help feed and clothe the poor of the east end of Glasgow. The club also performed a second function as it provided a way of keeping young Catholics together in their leisure time.

After initial early success, following its foundation in 1888, Celtic went on to win six consecutive Scottish League titles between 1905 and 1910.

This not only gave the Irish community a sense of pride but gathered thousands around the Nationalist cause as several of Celtic's leading directors were well known supporters of Home Rule for Ireland.

Image source, ALAMY/Archive PL

Image source, ALAMY/Archive PLScots attitudes to Catholic Irish migrants

Irish migrants arriving in Scotland often found it hard to assimilate into Scottish society. While Irish Protestants typically found it easier due to sharing a common religion with the majority of Scots, Irish Catholics experienced prolonged prejudice and discrimination from the outset.

Many Scots looked down on the Irish migrants, seeing them as ignorant and immoral. There were fears on how the arrival of large numbers of Irish people would affect the broader Scottish population.

The immigration of such a number of people from the lowest class and with no education will have a bad effect on the population. So far, living among the Scots does not seem to have improved the Irish, but the native Scots who live among the Irish have got worse. It is difficult to imagine the effect the Irish immigrants will have upon the morals and habits of the Scottish people.

Tension over Irish migrants in Scotland

There were fears expressed that the arrival of Irish migrants willing to work for lower wages would lead to poorer pay and worse working conditions for Scottish workers. The mass migration of the middle 1800s onwards also led to increased competition for housing which led to resentment.

During times of economic hardship, prejudice against Irish migrants – especially Irish Catholic – tended to worsen. The depression of the 1920s and 30s saw a rise in discrimination:

- workplace discrimination against Irish Catholics grew

- the Church of Scotland became more openly critical of Roman Catholicism

- militant Protestant societies were formed. Some, such as the Protestant Action Society, were involved in anti-Catholic riots

There were some positive steps as well, though. Irish Catholics were able to find representation in political parties such as the Labour Party and the Liberals – with some becoming senior party members or MPs.

The 1935 sectarian riots in Edinburgh by the Protestant Action Society were widely condemned by the Scottish press and the leading activists were punished by the law courts.

Test what you have learned

Quiz

Recap what you have learned

Irish Catholic migration to Scotland occurred in waves.

- early waves of Irish Catholic migration was temporary

- permanent, large-scale settlement began with the Irish Potato Famine (1845-49)

Irish Catholic migrants in Scotland were generally unskilled:

- they took low paid work in mills, factories and mines

- they tended to have poorer living conditions

- they often spoke only Gaelic

- they practiced a different religious faith to the largely Protestant Scots

While they often faced prejudice and discrimination, Irish Catholics had a lasting legacy in Scottish society and culture:

- Irish Catholic communities raised money to funds schooling for their children

- political groups supporting Irish separation from Britain became popular in Scottish cities with large Irish Catholic-descended populations

- sports clubs set up to support Catholic communities – such as Celtic and Hibernian football clubs – made a lasting contribution to Scottish society

More on Migration and Empire

Find out more by working through a topic

- count6 of 13

- count8 of 13