Quick version

Over the period of a century or so, the Scottish Highlands underwent a dramatic and permanent drop in population. Huge numbers of Highlanders migrated from their home regions to other places.

- Highland landlords introduced sheep to their lands to maximise profits from wool

- tenant farmers faced unemployment and eviction from their lands

- this became known as the Highland Clearances

Other factors that encourages migration were:

- poverty – the economic boom of the Industrial Revolution did not spread to the Highlands

- poor housing – conditions were often poor and tenants had little in the way of security or rights

- hunger – bad harvests and the potato blight could lead to hunger and deprivation

Many Highlanders left their homes to find jobs and new lives in the growing towns and cities of Scotland's central belt or in England. They often found work in the mills and factories that were booming thanks to the Industrial Revolution.

Hundreds of thousands of others emigrated to start new lives in the territories of the British Empire such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Video - Highland migration

This Higher History video explores the reasons for the migration of Highland Scots during the 19th century.

In the early 1800s, for tenant farmers of the Highlands, life was a struggle…

“They often felt what it was to want food … They were miserably ill clothed, and the huts in which they lived were dirty and mean beyond expression.”

Many farmers and crofters in the west of the Highlands and Western Isles relied on potatoes both as a source of food, and to sell. But starting in 1846, the potato crops were hit by the same blight that was ravaging Ireland. 200,000 people faced starvation.

For some time, landowners had been realising that they could make more money through sheep farming. They began evicting families from their lands, sometimes burning cottages to make sure their tenants could not return.

For those who lost their work and their homes in this way, there were two main choices – moving to the growing industrial cities in the central belt or England, or moving overseas.

There were many pull factors towards life in the city – paid work, wider community, sometimes even leisure activity such as football games.

But conditions weren’t easy…

“The … dwellings of the poor are situated in very narrow and confined closes or alleys …the space between the houses being so narrow as to exclude the action of the sun on the ground. … where I have noticed sewers they are in such a filthy and obstructed state that they create more nuisance than if they never existed“

Taking the risk of emigration could lead to a very different life.

The Canadian government even sent full time agents to Scotland - they toured markets persuading people to emigrate, with offers of free land.

The British Empire needed workers, and Scots were seen as hard-working and adaptable. Unskilled labourers tended to opt for Canada, New Zealand and Australia, while skilled workers preferred India, South Africa and the USA.

There was a real opportunity to get better wages: a worker in America could earn as much in a day and a half of work as a worker in Scotland would earn in a week.

The result was a dramatic decrease in the Scottish population.

Between 1830 and 1914, 600,000 Scots moved to England – and two million crossed the oceans to start new lives in the countries of the Empire.

Learn in more depth

The migration of people from the Highland regions of Scotland is tied to the chapter of Scottish history known as the Highland Clearances.

This period saw serious depopulation of the Highland areas - sometimes forcefully. This mass migration led to lasting changes to Scottish life and society. In particular, the Gaelic heritage of the Highlands was permanently affected as communities that had existed for hundreds of years disappeared. The language, traditions, and culture virtually vanished in many areas.

The percentage of Scotland's population that occupied the Highlands declined dramatically:

- in 1831 the population of the Highlands was 200,955 or 8.5% of the total population of Scotland

- in 1931 the comparable figures were 127,081 or 2.6%

The Highlands before the Clearances

Before the Clearances began in the 1780s, most Highland families lived in townships, in a kind of collective, or joint-tenancy farm, housing perhaps a hundred or so people – most likely all family or relations.

Most of these families had lived on the land for generations and saw themselves as having as much of a right to the land as the Laird. However, since most crofters held their land tenancies on a yearly basis, landlords held the power of eviction.

As in the Lowlands, most people were worked in subsistence agriculture – raising crops and livestock for their own needs and selling on any small surplus they had.

There was little in the way of industry, and any products or goods were created locally in small-scale cottage industries.

As the 18th century drew to a close, Highland landlords began to feel the need to make their land yield as large a profit as possible. Some merely increased the rent that their tenants paid for their land, while others looked to more radical changes in the use of their land.

Land use changes in Highlands

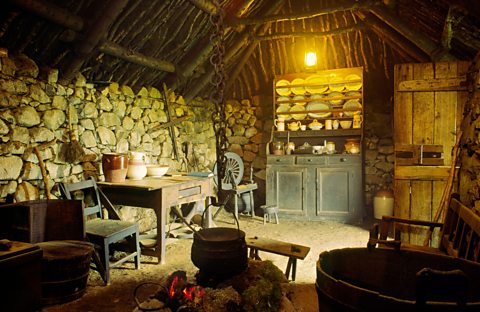

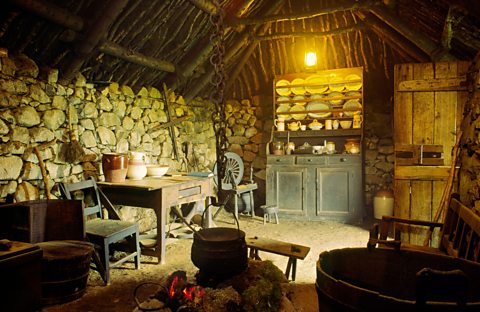

Image source, Chris Lock/ALAMY

Image source, Chris Lock/ALAMYFrom the late 1700s, many Highland landlords sought to capitalise on the economic opportunities of the Industrial Revolution. The traditional income derived form leasing land to tenant farmers was dwarfed by the profits to be made by farming sheep.

The Industrial Revolution saw an explosion in the number of textile mills. New weaving and spinning machinery allowed the mass production of textiles and cloth. The rise of the British Empire saw an expansion in the overseas market for Britain's industrially produced goods.

As most of the mills and factories were in Central and Southern Scotland, or the new industrial cities in England, the profits and developments of the Industrial Revolution felt very remote to Scots in the Highlands.

Image source, Chris Lock/ALAMY

Image source, Chris Lock/ALAMYThe Highland Clearances

Image source, Jan Holm/ALAMY

Image source, Jan Holm/ALAMYTo meet the demand for raw materials in the textile industry, many landowners turned their land over to the raising of large herds of sheep to harvest the wool for use in these textile mills. Scottish landowners in the Highlands were no exception.

Scottish landlords began to introduce hardy breeds like the black-faced Linton and the Cheviot breeds that could thrive in the tough environment of the Scottish Highlands.

In pursuit of greater profits some began to turn tenant farmland into pasture land for large scale sheep farms. The tenants and their families who had lived and worked there were moved off the land – sometimes by force.

Commonly, tenants were moved to new coastal communities to free up land for sheep. A significant problem was that most of the families were farmers not fishermen, and struggled to feed their families.

Families that tried to stay in their old homes fared little better. The heather and gorse that they raised their cattle on was burned to promote the development of grass that the sheep needed as feed.

The old homes of many evicted tenant farmers were also burned so that return was impossible.

Image source, Jan Holm/ALAMY

Image source, Jan Holm/ALAMYCrofting and the subdivision of land

In the Highlands, the sub-division of land into crofts led to economic hardship for many families.

Crofts were small areas of land where people lived and worked as farmers. Highlanders used the land to keep animals like cows and sheep, as well as for planting and growing food. The land was rented from landowners.

Families often subdivided the land between their children, so over time, conditions became more crowded and families tried to survive on smaller and smaller plots of land.

During the Highland Clearances, tenants were often moved to crofting communities on poorer quality land so that good land could be used for more profitable types of farming such as raising sheep.

The small size of the crofts and the poor quality of the land meant that many crofting families were barely able to grow enough food to feed themselves.

The poverty and hardship of crofting life was enough to convince many Highlanders to try to find a new life elsewhere.

The Crofters' War, 1800s

Throughout the 1880s a series of conflicts arose in the Highlands between crofters and the landlords they rented their homes from. They became known as the Crofters' War.

Already poor, and suffering after bad winters, crofters in Skye protested the removal of the shared grazing lands they relied on to raise animals by refusing to pay rent. Violent skirmishes followed, and the protests spread to Highland areas on the mainland.

While the Crofters' Holding (Scotland) Act of 1886 provided some legal rights to crofters, the hardships of crofting life led many Highlanders to try to find a better life elsewhere.

Other reasons for Highland depopulation

There were other issues that promoted migration from the Highlands.

- poverty

- poor housing

- hunger and disease

- tourism

Highland poverty

Image source, David Lyons/ALAMY

Image source, David Lyons/ALAMYAs well as the loss of agricultural jobs, coastal fishing communities in the Highlands saw their incomes plummet.

The income of most families in the Hebrides (and many in the rest of the highlands) was dependent upon earnings from seasonal at east coast fisheries that processed herring.

Prices of herring fell between 1884 and 1886 as a result of record catches and higher European import duties. As a result, wages also went into decline. The average earnings of a Hebridean seasonal worker fell dramatically from £20 to £30 (per season) in the early 1880s to only £1 to £2 a decade later.

The net result was that the Highlands of Scotland missed out on the economic opportunities experienced in the towns and cities of the Central Belt.

Another key industries that employed Highlanders was the kelp – or seaweed – industry. Kelp was used by agriculture as fertiliser, and burnt kelp ash was also used in manufacturing processes industry.

By the middle of the 1800s, the kelp industry collapsed as other chemicals that were cheaper to manufacture began to be used in industry. The result was that Highlanders lost another important source of income.

Image source, David Lyons/ALAMY

Image source, David Lyons/ALAMYPoor housing in the Highlands

Poor quality housing has also been cited by historians as a contributing factor to Highland migration.

Highland houses were typically made of clay and wattle, or of thickly cut turf. The roofs were thatched in heather, broom, bracken, straw or rushes. They were often badly built and lacking in basic essentials. In such houses dampness, dirt, cold, and smoke were constant problems. These conditions could lead to ill health.

Hunger and disease in the Highlands

With most Highland Scots living in subsistence agriculture, the failure of harvests due to adverse weather, pests, or disease could lead to hunger, poverty and deprivation.

The potato famine that led to mass starvation and migration in Ireland in the 1840s and reaches Scotland at the same time. While Scottish farmers were less dependant on potatoes as a staple crop, the fungus that wiped out several years of Ireland's potato crop also caused severe hardship in the Highlands.

Likewise, periodic outbreaks of diseases such as cholera occurred in the 1800s that weakened already diminished Highland communities.

As a result, many Highland Scots sought a better life with more opportunities elsewhere.

What was 'Balmoralism'?

Image source, imageBROKER.com/ALAMY

Image source, imageBROKER.com/ALAMY'Balmoralism' or 'Highlandism' was a term that described the romanticisation of Scotland and, in particular, the Highlands.

When Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, purchased the Balmoral estate in Aberdeenshire in 1847, they made the Scottish Highlands fashionable among the British aristocracy and growing middle classes.

The royal connection to the Highlands led wealthy families to purchase other Scottish lands and castles. Many were turned into hunting and shooting estates to cater for the emergence of an early tourist industry.

The success of these estates further led to the ongoing process of the Highland Clearances as tenant farmers were moved away from profitable land to make room for more hunting estates. This tourism increased with the arrival the railways in Scotland.

Image source, imageBROKER.com/ALAMY

Image source, imageBROKER.com/ALAMYMigration from the Highlands

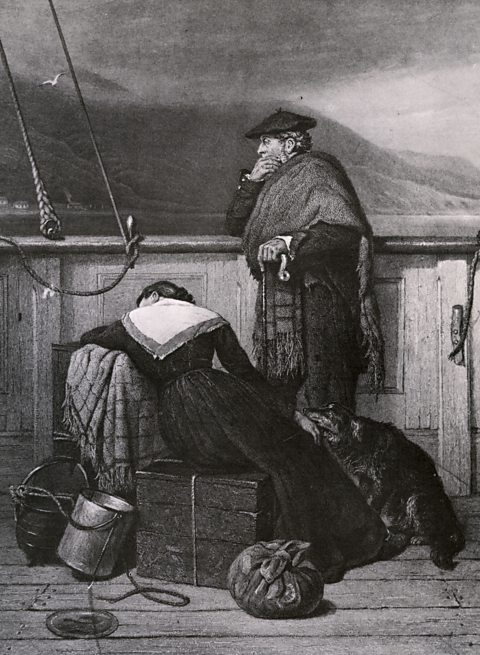

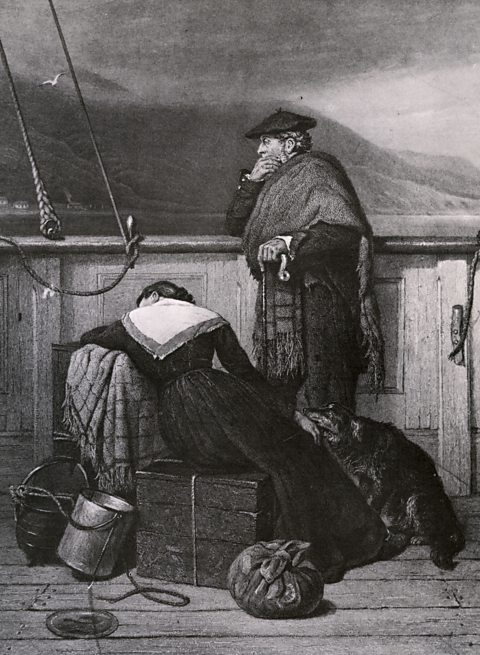

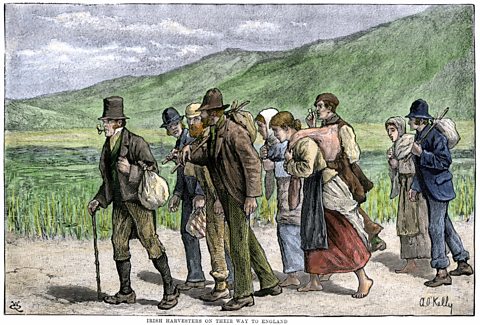

Image source, Pictorial Press Ltd/ALAMY

Image source, Pictorial Press Ltd/ALAMYWhile there were many Highlanders who were forcibly moved from their homes, there were many more who left voluntarily. While some were resettled into new communities established by landlords, the majority sought a new life outside of the Highlands.

There were other reasons that drove migration.

Life in the Highlands was tough. Arable land to support crops was scarce and the climate could be challenging. Farming was hard and many Highlanders lived in poverty and were at risk of hunger.

The towns and cities of the Lowlands, and the mills and factories found there, offered the prospect of year-round employment, better pay, and often accommodation.

Many other Highlanders chose a more dramatic option – emigration to other countries.

The settlements and colonies of the expanding British Empire had a need for labour and settlers. Employers in the overseas colonies sent agents to tour the Scottish Highlands to recruit and persuade Highlanders to emigrate. Some landlords even paid the travel costs of their Highland tenants.

Such large numbers emigrated, that Highland Scots would go on to be a significant presence in countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Image source, Pictorial Press Ltd/ALAMY

Image source, Pictorial Press Ltd/ALAMYTest what you have learned

Quiz

Recap what you have learned

Over a century, the Scottish Highlands underwent a dramatic drop in population as huge numbers of Highlanders migrated from their home regions to other places.

- Highland landlords introduced sheep to their lands to maximise profits from wool.

- Tenant farmers faced loss of livelihood and eviction from the lands.

- This became known as the Highland Clearances.

Other factors that encourages migration were:

- poverty – The economic boom of the Industrial Revolution did not spread to the Highlands

- poor housing – conditions were often poor and tenants had little in the way of security or rights

- hunger – bad harvests, and the potato blight in particular, led to hunger and deprivation

Many Highlanders left their homes and migrated to find jobs and new lives:

- Some moved to find work in the factories and mills in Scotland's towns and cities

- Hundreds of thousands of others emigrated to the territories of the British Empire such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand

More on Migration and Empire

Find out more by working through a topic

- count3 of 13

- count6 of 13