VOICE OVER:

Ernest Steele was born in Hackney, where his father ran a thriving box making factory.

JULIA HOFFBRAND:

He had a very decent education, but then left when he was 15 and started working in his father’s business.

EMMA SUTTON:

I knew that there were cardboard boxes, but I’ve never seen these sort of pictures. And – and I never got a sense of the scale or – or that they were actually doing quite well for themselves.

DAVID EMPSON:

This is the house he was born and grew up in and from which he entered the army in 1914.

EMMA SUTTON:

That’s fantastic.

DAVID EMPSON:

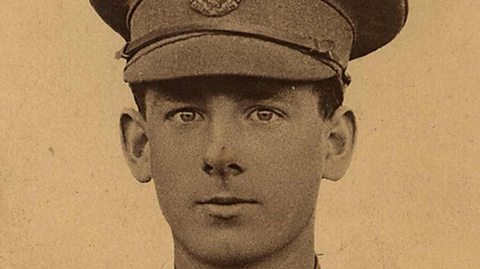

There he is as a young teenager, obviously just joined the army.

EMMA SUTTON:

So young.

DAVID EMPSON:

So young.

VOICE OVER:

In August 1915, Ernest was sent with his regiment to Ypres in Belgium.

ERNEST:

‘Dear Mater and Pater, since I last wrote lots of things have happened.’

‘Arrived Havres 12 midnight, parade in afternoon.’

VOICE OVER:

In his own diary, Ernest recorded how he’d been given a chance to escape the war.

ERNEST:

‘Sergeant Clifford told all under 19 years of age could go back to England if they wished. After long discussion we decided to stay.’

EMMA SUTTON:

That shows a real commitment to his comrades. He couldn’t desert the other people who were already out there.

VOICE OVER:

Ernest had arrived in the midst of the war’s first great bloodletting at Ypres. There were 60,000 British casualties.

ERNEST:

‘In the evening went up to firing line.Got over near Houge when mine went up and then over came umpteen shells and rapid fire.’

‘I fell over a dead man. I got hit slightly. I’m feeling rocky. Wrist hurting slightly and nerves going. Iodine for wrist and rum for nerves.’

EMMA SUTTON:

He’s being shot at and people are falling around him. And he’s only a young boy, isn’t he? I think it’s quite shocking.

FERGAL:

We also know war is taking a deep strain on him from a letter that he sends back to his brother.

ERNEST:

‘Dear Harry, I heard from Mater last night and she said you wanted to join up. Now, I’m going to talk to you seriously, so look out! You may feel old and strong but you’re only 15. Therefore you’re too young to stand the strain of anything approaching this. I’m over three years older than you and even I am beginning to think I’m not much use out here.

EMMA SUTTON:

He wants him to be alive when he goes back. Maybe that’s something that he’s looking forward to, is going back and seeing his family. You have to have that hope when you’re in war that you are going to go home.

VOICE OVER:

But the horrible loss of life that Ernest witnessed in Ypres was to be far exceeded at his next posting on the Somme.

ERNEST:

‘The bombardment started at 5.30am. Regiment over the top at 7.30, and reached the German fourth line. But owing to division on right failing, we had to retire, with enormous casualties. Out of 3,000 only 600 got back. A division covered in glory – and gore.’

VOICE OVER:

Ernest escaped the slaughter of the Somme and fought his way through another two years of war, by which time the allies were engaged in their final offensive.

By late 1918, the war was almost won, and the boy who had spurned the chance to return home on his second day in France had seen it through to the closing phase.

Now a Second Lieutenant in the machine gun corps, on the evening of the 17th September Ernest was in Épehy preparing for battle the following day.

ERNEST:

‘Dear Mater and Pater, as I don’t suppose I shall have a chance of writing you again for a few days I thought I’d take the chance of letting you know so that you shouldn’t worry. I think we’re winning the war hand over fist now and it won’t last much longer. I realise more than ever all that you have done for me and wish I could have a chance to repay you at least a part. The best of love from your affectionate son, Ernest.’

FERGAL:

Early on the morning of September 18th, Ernest and his machine gunners moved forward ahead of the main group of troops.

The German lines are all across here. They’re setting up their machine gun positions so that they’re going to be able to lay down fire for the infantry as they move forward.

Ernest and his men go into the view of the German troops at the top of the hill. Here at this point Ernest is hit by a German sniper. And he’s killed instantly.

EMMA SUTTON:

It’s – it’s a sad ending, but I guess a lot of the men who came out had this ending. And not the - not the returning home and telling Mater and Pater all about it that he’d hoped.

Video summary

Ernest Steele volunteered to fight for his country in late 1914, even though he wasn't yet nineteen - the minimum age a soldier could be sent abroad to fight in World War One.

In August 1915, he was sent to the Belgian town of Ypres, probably the most dangerous place for a British soldier to be stationed on the whole of the Western Front. In response to popular pressure, the army gave underage soldiers the opportunity to return home but Ernest Steele refused to take up this opportunity.

Whilst in the village of Hooge, he was injured and this film describes the quite primitive way in which his injuries were treated.

Ernest was so shaken by his early experience of warfare that he tried to dissuade his younger brother, then aged fifteen, from signing up.

As well as seeing action at Ypres, Ernest fought as part of the Somme offensive, before eventually being killed by a German sniper in the closing months of the war.

Contains scenes that some viewers may find upsetting. Teacher review recommended before using in class.

This film is part of the series Teenage Tommies.

Teacher Notes

The government found it harder to recruit army volunteers in 1915 than they had in the early months of the war. Using Ernest Steele’s letter to his brother as a stimulus, pupils could provide reasons why the number of volunteers reduced as the war progressed.

This clip will be relevant for teaching history. This topic appears in OCR, Edexcel, AQA, WJEC KS4/GCSE in England and Wales, CCEA GCSE in Northern Ireland and SQA National 4/5 in Scotland.

Aby Bevistein. video

Aby Bevistein, an émigré from Eastern Europe, joined the Middlesex Regiment in September 1914 aged only 16.

Cyril Jose. video

Cyril Jose joined the Devonshire Regiment, even though he was only 15 years old.

Horace Iles. video

Horace Iles was travelling on a Leeds tram when a stranger presented him with a white feather, even though he was only fourteen years old.

St John Battersby. video

St John Battersby, the 14-year-old son of a vicar from Blakeley in north Manchester, signed up to join the army against his father's wishes.