- Contributed by

- actiondesksheffield

- People in story:

- *WALTER HOBSON*, Dr. Johnson, Sgt. Holmes, Jack Slingsby, Len Hoy, Dickie Clayton, Major Cleaver (My C.O.), A.J. Cronin, Pony Moore, Walter Wilson, Bill Cotton, Reg Sykes, Jack Richie, Jerry Strachen, Sgt. Major FrieCol John Frost, Bill Bennetl, Brian Watts and Jack Wright

- Location of story:

- UK, North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Austria, Switzerland & Germany

- Background to story:

- Army

- Article ID:

- A4178487

- Contributed on:

- 11 June 2005

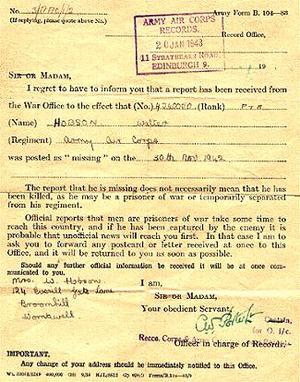

Missing In Action Letter.

This story was submitted to the People’s War site by Bill Ross of the ‘Action Desk — Sheffield’ Team on behalf of Walter Hobson, and has been added to the site with his permission. Mr. Hobson fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

==================================================

This story tells in graphic detail, of the incarceration within the many P.O.W. camps that the contributor of this story was forced into, during WW2. It also describes the squalid, degrading and sub-human conditions that he was compelled to endure, not only within the camps, but whilst ‘on the run’ from them. The deaths of and devastating injuries to his colleagues, whilst actually in his presence, are also described………Bill Ross - BBC People's War Story Editor.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Other parts to this story can be found at:

Pt 1:..... a4178333

Pt 2:..... a4178360

Pt 3:...... a4178388

Pt 4:..... a4178423

Pt 5:..... a4178450

Pt 6:..... a4178487

Pt 7:..... a4178496

Pt 8:..... a4178504

------------------------------------------------------------

We were marching down a road, when all of a sudden, we stopped, and the Jerries stated to mumble among themselves. There were some tanks coming along, all Yankees. They threw us some cigs and they said, “We’ll be back.” So, what happened was, we took over, so the guards that had been guarding us, we were guarding them now. We took their rifles and everything off of them, now they were our prisoners. The Yanks did come back about half an hour later, and they said, “Take ‘em down that road there, and you’ll find a lot more.” There was a big field full of Jerries. One of the Yanks said, “If there’s any o’ these that’s ill treat yer, any that have done anything to yer, now yer can get yer own back.” But they were all old soldiers and what have ya? They took us into a village and they got whoever was the Lord Mayor, I’ve forgotten what they called him, and they said, “Right, all these lads have got to be billeted.” There were families all saying, “Come to my house, come to our house.” There was a little lad, about eight years old, and he got hold of my hand and said, “Come.” Anyway, we went to his house, and they (the boy and his mum) kept us, just us two, and, apparently, her husband was out fighting the English. We were with them for about five or six days. Then they took us through to a big camp that was full of Yankees, and there were a lot of women-Yankee army women. They were like our A.T.S.

They were feeding us. The only snag was that their urinals were ditches and we’d to crouch down on the ditches. We were exposed to the world, but that didn’t matter. Anyway, we spent about a week there, then they said, “Right, you’re lining up for documentation, ready to go back home.” We were queuing up all day. There was only one table at the end, so they said, “Right, that’s enough, you can all come back tomorrow.” One of the lads said, “I’m going, I’ve found a way to get to the front.” So he got to the front all right; he was from the Sherwood Foresters, and he got away a day before us. But what we learned later was that the plane he went on, crashed and they were all killed. So in a way, I was lucky.

We got through, to an aerodrome, and eventually, we were back home. We landed back home in Buckinghamshire, High Wycombe I think it was. When we got off the plane there, the Women’s Voluntary Service were waiting for us. They took us, two to each lad, to a big hangar where we were deloused. They shoved a hosepipe up our trousers leg, down our breeches, up our jacket sleeve, and there was a white powder. We needed it ‘cos we were well loused. Then they took us to a camp. At half past one in the morning, I was having a shower in this camp. Next morning, when we went for our meal, who should be in charge of the camp? An old school mate o’ mine, Sid Hurst. He sez, “Eyop, there’s hundreds passed through me and you’re the only one I’ve known.” So he said, “I’ll tell ya what, I know you’ve not had a lot to eat, but you can have as much as you want here, but take a tip from me. Only have a bit.” He said, “They’ve been gorging themselves, then they’ve been sliding under the tables and passing out. They couldn’t take it.” Our stomachs were only as big as a golf ball. He said, “If thuz owt tha wants to tek back wi’ thi’, I’ll fill thi pack. (If there’s anything you want to take back with you, I’ll fill your pack).” But all I was bothered about was getting back home. In three days there, we had two pay parades, no, it was less, it was a day and a half. We got all the documentation and took a train, and we set off back home.

We got to Sheffield station; we’d to make our own way from there. I managed to get to Wombwell station, then I got the 70 bus outside the station. Who should be on it? Some girls from the munitions. One in particular, instead of stopping and helping me carry my kit, went flying home. She said, “Your Walt’s comin’ dahn t’lane.” My daughter then was six years old, and there’s her and about six or seven mates, all came flying up the road, and she was saying, “That’s not me dad.” I said, “Ah, but I am old love.” I picked her up, and all the kids carried my kit. When I got home, there was a big thing over the door, “Welcome home Walt,” and all that. It was something I’ll never forget for as long as I live. After that, I think I got about 28 days leave, and then we’d to go back, to Gosforth, in Newcastle. All different units were there, and we had a bit of training. I had to go in front of the Medical Officer and I was declared unfit. They said, “You can have your release,” but I said, “Yeah, but I don’t want it.” “Why?” I said, “Well, I’ve been in touch with the man I used to work for, and he’s assured me I can get out of the army on Class B to do my regular work, bricklaying.” He said, “Oh, fair enough then, we’ll let you have that.”

In the meantime, what they did, they sent us to Ilkley on what they called a C.R.U., a Civil Resettlement Unit. We could wear civvies or uniform. They’d take us round all different places of work in England, northern England, Yorkshire etc., We went to Johnson and Johnson, we went to the Labour Exchange, painters and decorators, allsorts. If we saw a job we liked, they’d try and get it for us. The kid I was going around with then was, Bernard Crossley-Dent from Leeds, and he was a painter and decorator; they got him a job. I said “I have got a job to go back to,” which I had, back to the old firm where I’d worked as a brickie. I think we did seven weeks there, at Ilkley. The A.T.S. were looking after us. It was back to Civvy Street then, and that’s about it.

I know, when I look back, I didn’t know how lucky I was. I was very very lucky.......>

Pr-BR

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.