- Contributed by

- actiondesksheffield

- People in story:

- *WALTER HOBSON*, Dr. Johnson, Sgt. Holmes, Jack Slingsby, Len Hoy, Dickie Clayton, Major Cleaver (My C.O.), A.J. Cronin, Pony Moore, Walter Wilson, Bill Cotton, Reg Sykes, Jack Richie, Jerry Strachen, Sgt. Major FrieCol John Frost, Bill Bennetl, Brian Watts and Jack Wright

- Location of story:

- UK, North Africa, Sicily, Italy, Austria, Switzerland & Germany

- Background to story:

- Army

- Article ID:

- A4178450

- Contributed on:

- 11 June 2005

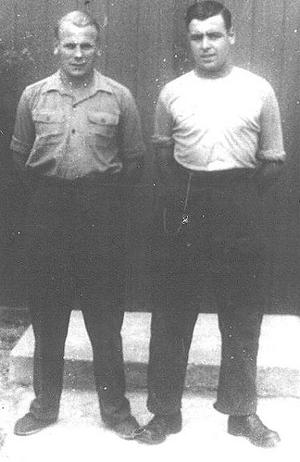

Jack Richie and Walter as P.O.W.s.

This story was submitted to the People’s War site by Bill Ross of the ‘Action Desk — Sheffield’ Team on behalf of Walter Hobson, and has been added to the site with his permission. Mr. Hobson fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

==================================================

This story tells in graphic detail, of the incarceration within the many P.O.W. camps that the contributor of this story was forced into, during WW2. It also describes the squalid, degrading and sub-human conditions that he was compelled to endure, not only within the camps, but whilst ‘on the run’ from them. The deaths of and devastating injuries to his colleagues, whilst actually in his presence, are also described………Bill Ross - BBC People's War Story Editor.

============================================

Other parts to this story can be found at:

Pt 1:..... a4178333

Pt 2:..... a4178360

Pt 3:...... a4178388

Pt 4:..... a4178423

Pt 6:..... a4178487

Pt 7:..... a4178496

Pt 8:..... a4178504

There were no window frames, just a hole. So he said, “Yeah, OK.” I went out and there were two guards there. They said, “Where’s your friend?” I said, “Alright Jack, come on.” So he came out; then they marched us up a track to where there was a wire at the side (we’d three guards by this time), they said “Soldi, soldi,” that means money. I said, “Oh, they’re wanting our money.” We’d got what we’d been earning doing the bricklaying. I said, “Just gi’ ‘em a few bob, don’t gi’ it ‘em all, we might want some later.” So we gave them a handful of notes. Then they took us to the wire and they’d made a hole in it. They sent us through and told us, “Head north! Keep heading north.” We’d already been told that, and that we were to avoid towns. So we set off and it was moonlight, dark and cloudy. So, we were trundling on, then we came to another wire, a big wire with bells across the top. As soon as the wire was touched, the bells rang.

I said, “This must be no man’s land that we’re in, I reckon if we get through that wire, we’ll be in Switzerland.” But under the wire, they’d put bits of wood and bits of railing etc., so I got hold of one and pulled it back. Jack crawled under, and when he’d gone under, he shoved it back for me.

We set off through the fields and we came to the mountains. I said, “Oh, these must be the Swiss Alps.” I started climbing up a mountain, but it got dark. We tried to follow what we thought was the North Star, but all of a sudden, I disappeared. I went rolling over; I’d fallen down a ravine. I was in a right state. I could hear Jack saying, “Walt, weer ah tha? Weer ah tha? (Yorkshire dialect, Where are you?). I’d smashed my shoe and it’d made a blister on the side of my foot. Anyway, I scrambled back up, set off again and got back down, then through the fields and arrived at a road. We were marching up the road, when all of a sudden, we could hear, clomp, clomp, clomp, clomp, clomp. I said, “Oh, it’ll be the Swiss police.” I said, “Wi’s eter gi’ us-sens up sometime, (We’ll have to give ourselves up sometime), it might as well be now.” This was about 3 o’clock in the morning. Anyway, we went straight to ‘em; it was two German guards. “Andioch! Andioch!” And we were in civvies. Anyway, they prodded the bayonet into us and told us to walk on, put our hands on the back of our heads, and all this stuff. They took us to their headquarters and they got this Jerry officer out of bed. He was grumbling and grousing. I could hear him swearing, and he kept saying something to us, but I couldn’t tell what he was saying. . I sez to Jack, “Wot the dickens e on abart? (What’s he talking about?)” So he said, “Are you English?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Why didn’t you say so?” I said, “Nobody’s asked us.” He said, “What do you think I’ve been asking you for the last ten minutes?”

So, he asked us what we were doing, we told him we were escaped prisoners. Where had we been etc.? So he said, “Right, lock ‘em up.” So they shoved us into a…….I don’t know what it was, a coalhouse or what. When we got inside, there were a lot of spuds, potatoes; that was our bed. Anyway, the next morning, they whipped us out; they said nothing about washing or anything like that. They took us through to a big hall, like a school hall. Inside the hall, was a series of desks, and there were two at each desk. We found out that one was a German officer and one was an interpreter, and there must have been twenty of these. They took us in one at a time and they sat us on a stool in the middle. We’d arranged what to say beforehand; it’s a good job we had. I said, “For goodness sake, don’t tell ‘em who’s helped us. If they say ‘weer’ve ye got yer clooers, tell ‘em wi’v pinched ‘em (If they say (where have you got your clothes, tell them we’ve pinched them). And tell em, ‘look, wi’v bin livin’ offer t’land soorter thing’ (and tell them ‘look, we’ve been living off the land, sort of’).”

Anyway, they set off asking questions, they asked them from different points of view, and they’d ask us the same question three or four times in different ways. What they wanted to know was, “…….where are you from? What camp have you escaped from? Where have you got your clothes? Who had given them to you? Who has helped you? How have you been living?” Well, we daren’t tell ‘em for the life of us. I mean, they’d have gotten into trouble wouldn’t they?

They put us into jail, Milan Jail; we’d got fourteen days for escaping. When we went in, there were some more lads in there. We’d got a blanket, cut it in two, half for me and half for Jack, and that was our bed. In this room, which was about 10 by 10 (feet), there were seven plant pots, well, I called them plant pots, in the corner, with just a board round, like a shield. That was our toilet. Seven of us had to live in that place. They used to let us out for one hour a day, and that was for washing and toiletry etc. Apart from that, we were locked up, on the top floor in Milan jail. I’ll never forget that; not very happy days. But I guess it was all part of living in those days. After we’d spent the fourteen days in there, they took us to a barracks. There were some more lads, about seven of them. Of course, we were dressed in civvies, and they were in a mixed uniform comprising green trousers and light blue jacket. On the table in front of us were a loaf of bread and a tin of jam. We got to talking, and one of ‘em said, “Are you English?” “ I said, yeah, what about you?” “We are.” They said, “You don’t look it.” “I said, “No, we were in civvies and this is the uniform they’ve given us.” Anyway, they came with us; I’d a pair of light green trousers, a blue jacket and a khaki, French cap. Oh, and a grey shirt, and that was it. That was our uniform; anyway, we’d to stay in these barracks, under guard. The officer came one day and said, “You come with me.” He took Jack and me; we went into a house, attached to the barracks. There were two women in; one was his wife. She’d never seen an Englishman, so she wanted to have a look at what we were like. Ha! Ha! We were on show. Anyway, we stayed in those barracks for about a month, and, there was a Serbian Sergeant Major, whom I got pally with. Me and him, we used to wander as far as we could around the barracks. We couldn’t get out, there was no way out. But then, we found a road out of the back. We’d to get through the wires. I said, “Sithi, wi’ ‘n gerart er ‘ere (Look, we can get out of here).” I said, “Well, wi’s e’ te’ get prepared (we’ll have to get prepared), get some food.” So, we decided to get some food and said, “Right, tomorrow, we’re going.” Just me and him. But of course, I was taken bad with pneumonia wasn’t I? I was in a right state; I didn’t know what it was, I thought it was just ‘flu. The Italians, whom we’d been bartering with, through the window, wanted to know where I was, and they sent a doctor. Jerry let the doctor come in and attend to me. He gave me some pills and what not, took my temperature and told me to keep wrapped up. Well, the Sergeant Major, he went without me; he went on his own and got away. I was still a prisoner.

They took us through the Brenner Pass, then into Austria. We went to a camp there, near Moosburg, and at this camp, there were a lot of civilians. There were men, women and kids, and there was a compound, full of French and Belgians, but the compound that they put us in was full of Americans and English. There were long rows of beds, three storeys high, no bedding at all. One day a week, they used to take us into this big concrete blockhouse thing. It had no windows in, just one door that we went through. In the middle of the ceiling, was an aperture, and they used to put a hose pipe through, with water, cold water of course. That was our bath, but before we went in, we’d to take everything off, and the clothes went on a belt, then on to the end to be deloused. We got our clothes, well, we might not have got our own clothes, but we got some. Anyway, what we didn’t know was that the ‘shower’ was a gas chamber. If they didn’t want to put water through, they would put gas through. I thought, well, I’ve been two or three times in there, and when I think about it afterwards, they could have done away with us couldn’t they? So, we stayed there about a month, after which they took us through into Germany, to Camp 11B. There, we had to work in the iron ore mines. They used to march us off in the morning, around 4 a.m. if we were on days; we’d march about three miles, work a shift, come out and march back. If we were sick, that didn’t matter, we still had to go. I did quite a few weeks down the pit there. It was boring, tiring, all the lot, and I’m goina tell ya, it was heavy work, very heavy.

They started to let us use the baths after a while, but they didn’t provide us with anything, no clothing or anything. We used to get bathed, then get back into the same clothes that we’d worked in because that’s all we had. One day, they decided to let some of us work on the pit top. We’d a nickname for all the deputies: one we called Fishface, one we called Weasel……..well, I can’t remember them all, but there were all sorts of funny names. But while we were down the pit, we had settling lamps and Fishface had a stick; all deputies had sticks, as you know, they do in our pits. What he did, he got hold o’ one o’ our lads, and he was brayin’ (Yorkshire dialect, “hitting”) ‘im wi’ t’stick, so we went across to him and took his stick off him and threw it away. Then he started with the lamp, so we took the lamp off him. Anyway, they had us up in front of the camp Commandant and we explained what had happened. He let us off that particular time.

When we were on the pit top, my first job every day was to get two sacks of dandelion, clover and such as that to feed the rabbits for the deputy. Well, because I had been messing with the soil, on my hand I got a wicklow. I was in pain, I couldn’t go to work because my fingers had swollen up. I said to the Medical Orderly, “Look at this hand.” He said, “What yer done?” I said, “It’s a wicklow, well, I think it is.” So, they got a German doctor who came in on a Friday. He said, “Right, we’ll have to operate.” They didn’t give me any aneasthetic or anything, he just ordered a German guard to hold my arm, and he just cut it. I nearly went mad. A couple of days later, it was still swelling up and there was like, yellow stuff coming from it, so I showed it to the orderly again and he said, “I’ll show it to the officer when he comes.” When the medical officer came, he said, “Oh! I’ve cut it the wrong way, I need to cut it up, over and down on the other side.” He said, “Get him ready for Friday.” So I said to the orderly, “What can I do?” So he said, “Can you get any salt?” I said, “Well, I don’t know, the only salt I’ve seen is in the German cookhouse.” But, I managed to get some salt, and I got some boiling water, put the salt in and I kept bathing it and squeezing it until I got all the puss out. Then when the doctor came on Friday, he said, “Oh, an abscess.” So he got a pair of tweezers and pulled the abscess out, and do you know, I can still feel that to this day; it still affects me after all that time, and that was 1943.

After a while, the R.A.F. came over, bombing, and each hit seemed to be on farms all around. On this particular day, came the order: “You’re not going to the pits today, you’re going to clear up these farms.” The farm that we went to, we were getting all the debris out of the way, and there was a big whicker basket in the middle of the farmyard. We went to this basket, and after a while, I could hear this clucking, so I went over and saw an egg. I got the egg and I managed to get it back to the camp in one piece where we boiled it. And that egg, six of us shared it. It was a novelty. None of us had tasted an egg for several years prior to that day.

They decided to move us again. Now, we stayed in the same camp, but they moved us to different works. This place where we were working, we couldn’t understand it at all. They were making a big ramp, and we were supposed to be working on it, but we wouldn’t. We were having our own way. The ramp was built on a hillside, and there were some wooden steps. I said to the lads, “We can get out here.” We climbed up a shaft, and there was a trap door at the top. We opened the trap door, and we were out into the fields. We all three got out, but there was somebody else. They said, “Have you told somebody else?” I said, “No.” But who it was, it was a German who’d followed us, and he took us back. He took us into the office, and the officer went wild. When we got back to camp, they said, “After all we’ve done for yer……….” I said, “Well, it’s our duty to escape and we were trying to escape.” Anyway, we fouled it up.

They took us on a march and they were trying to get us through to their lines. We marched all day and then they put us into a building for the night. We set off the next day, and as we were marching down a road. I said to this lad with me, “Geoff,” I said, “Look, work your way to the back.” So we went from the front to the back, and a corporal said, “Wot ye playin’ at, you two?” I told him, “We’re goina get away.” He said, “Don’t bother.” “Why?” I asked. He said, “’Cos we’re heading for the Yanks.” So I asked, “How do you know?” He said, “Can’t you hear that rumbling across the back?” I told him, “I thought it was Jerries.” He said, “That’s not, them’s Yankees.”.............>

Pr-BR

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author. Find out how you can use this.