Familiar and full of character, blue tits are one of our best loved birds. They busy themselves in our gardens, obligingly using our nest boxes and delighting us with their nest building, cleaning and feeding antics.

However, there is a creeping danger that’s threatening the lifecycle of our colourful feathered friends. Climate change is causing a timing mismatch between when blue tit chicks are at their hungriest and when the highest number of juicy caterpillars are available for them eat.

Blue tits collect moss to make a cosy nest for up to sixteen chicks (Photo: Duncan Day)

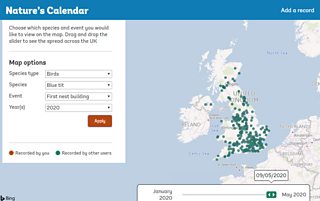

We need to understand more about blue tit nesting habits and the impacts of spring arriving earlier. Phenology – the study of the timing of natural events – can help us with this. Citizen scientists have been recording blue tit activity with the Woodland Trust’s phenology project, Nature’s Calendar, for over 20 years. More wildlife watchers are needed however to give us a better picture of what’s going on with blue tits across the UK.

When do blue tits nest?

Finding the perfect cosy cavity in which to raise your young can take time. Blue tits use a variety of locations, from tree holes and crevices to man-made structures and nest boxes. They’re often seen checking out their options before settling on a final nesting site. When you first spot a blue tit carrying material such as moss, grass and wool into the nest, you can record it on Nature’s Calendar.

Nature’s Calendar records show that blue tits usually begin nest building in late March or early April. However there’s quite a range in the dates every year. This spring our first nesting blue tit was recorded in Kent on 6 January.

Hatching naked and blind, blue tit chicks are entirely reliant on their parents (Photo: Jack Shutt)

Having taken up to two weeks to build the nest, the female then lays an egg every day – for up to sixteen days. The usual clutch size is 8-10 eggs and the female incubates these for a further two weeks.

Why timing is crucial for chick survival

While the blue tit egg weighs just about 1g, once hatched the chicks grow rapidly; they can quadruple in size in the three weeks it takes them to fledge. Hence parent blue tits do little but feed their growing young at this time. At their hungriest each chick can eat up to 100 caterpillars a day.

A webcam allows this Nature’s Calendar recorder an intimate insight into busy blue tit lives (Photo: Ingrid Leene)

As we have seen on BBC Springwatch this year, a female may especially struggle to raise her brood without the male around to help. Needing to find as many as a thousand caterpillars a day means it’s critical that blue tit breeding is synchronised with the rest of the food chain.

Early springs create a food chain ‘mis-match’

Using Nature’s Calendar records, scientists revealed how oak tree leaves come out earlier in a warmer spring. This correlates with an earlier peak in the caterpillar numbers too; oak and caterpillars have a similar sensitivity to this temperature increase.

When warm weather prompts an early spring, such as this year, blue tits need to breed in time to reap the rewards of the corresponding early caterpillar crop. However, the earlier that spring arrives the harder it is for birds to adjust the timing of their breeding. They just can’t keep up.

This can leave blue tit chicks to go hungry. The research, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, identified that great tits and pied flycatchers face the same challenge.

See where and when blue tits were first recorded nesting, or oak trees first leafing, using the live maps on the Nature’s Calendar website.

Climate change and the need for further research

Climate change is expected to bring earlier and warmer springs. The Spring Index is determined using Nature’s Calendar records and calculates the extent to which spring is advancing. Since 1999, spring has arrived, on average, 6 days earlier than in the first part of the 20th century.

Six days might not seem like much, but in the intricate life cycle of some plants and animals, it can make all the difference. Ultimately some of our wildlife will be able to adapt better than others.

Nature’s Calendar’s birch leafing records helped reveal how blue tit use trees as a cue for their breeding (Photo: Gergana Daskalova)

Understanding the complex interactions along a food chain is key to knowing how our wildlife will fair. Recent research using Nature’s Calendar records investigated how blue tits decide when to start breeding. Read more about this, as discussed by Chris Packham on Episode 2 of Springwatch, on our website.

How you can help

To inform this scientific research and more, Nature’s Calendar wants to know when a whole host of natural events happen near you. From blue tits on your doorstep to the last time your see a migrating bird, trees tinting, leaves falling and fruit ripening. Find out more on our website, naturescalendar.woodlandtrust.org.uk, and get some inspiration for spring and autumn events by watching our short videos.