Journalists should be equipped with theory as well as practical skills

Jon Silverman

is professor of media and criminal justice at the University of Bedfordshire

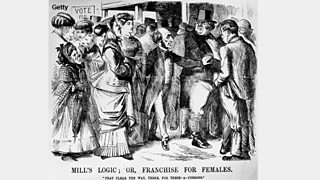

John Stuart Mill campaigns for votes for women, Punch magazine, 1867

But a brief primer on the laws and customs of war and how the writ of the International Criminal Court differs from the ad hoc tribunals set up by the UN Security Council would also have come in useful. In contemporary journalism, knowledge – both empirical and theoretical - is power.

Similarly, any journalist grappling with stories about control orders (now, TPims), the activities of Edward Snowden, the cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad and a myriad others would have their understanding greatly enhanced by a working knowledge of John Stuart Mill’s celebrated treatise, “On Liberty”.

Mill’s theorising of the battleground between individual independence and social control and his warnings about the ‘tyranny of the majority’ retain a freshly-minted ring in the era of YouTube, Facebook and Twitter.

Likewise, a passing acquaintance with the American sociologist Howard Becker’s concept of the ‘hierarchy of credibility’ to explain the confidence with which governing elites ‘define the way things really are’ is a useful theoretical tool in the journalist’s kitbag - before we all become incorrigible cynics about those who wield power.

I raise this, not to make journalists feel inadequate about the qualities they bring to their job but to suggest that amidst all the agonising about whether journalism is heading off a cliff-face, someone should be championing intellectual curiosity and the nourishing of what Denis Healey called a ‘hinterland’.

That’s why a small number of universities in the UK, including my own, the University of Bedfordshire (UoB), offer professional doctorate courses designed to find new ways of integrating professional and academic knowledge, in other words, to bridge the gap between journalistic practice and theory.

The length of the course will vary depending on the institution and whether it is undertaken full or part-time. For us Part One consists of three taught modules spread over one academic year, while the core of Part Two is a 50,000-word dissertation, which could be either project or policy-orientated. A broadcaster, for instance, could produce an analytical reflection on a documentary.

If successful, the candidate is awarded a doctorate and can bask in the satisfaction of making an original contribution to knowledge as well as, perhaps, enhancing their employability.

They may also emerge believing that the gap between theory and the day to day practice of journalism is not as wide as many working journalists think.

One of the journalists currently doing our ProfDoc found a reading of John Stuart Mill on freedom of speech and action relevant when preparing his dissertation on Panorama’s controversial programme, alleging corruption in FIFA, football’s world governing body - which was broadcast only days before it announced which bids for hosting the 2018 and 2022 World Cups had been successful.

As he noted, Voltaire’s celebrated nostrum about ‘defending to the death’ one’s right to say the unpalatable was ignored by much of the British media in its haste to condemn the ‘irresponsible’ BBC.

When I did my journalist training (in 1971, since you ask), our course organizers felt that what we needed was a cold douche of practicality rather than open-ended discussions about philosophy. There was no room for John Stuart Mill on the course agenda between the Teeline shorthand crammer and how to make the morning calls to police, fire and ambulance. But perhaps there should have been.

Jon Silverman is Professor of Media and Criminal Justice at the University of Bedfordshire and was the BBC Home/Legal Affairs Correspondent, 1989-2002.