#GE2015: Polling has never been nearly this social

Cathy Loughran

is an editor of the BBC Academy blog

We’ve had an insight this week into how seriously politicians are channelling their efforts - and funds - into making effective use of social media in the run up to what’s been dubbed the ‘hashtag election’.

News organisations are also, of course, marshalling their resources and digital tactics as 7 May approaches, and there was a pretty graphic glimpse of that at the latest News:rewired conference hosted in London by Journalism.co.uk.

They’ve clearly got a job on their hands to wrangle and make sense for voters of the cacophony of social chatter. One comparison with the last general election campaign summed up the size of the task.

Can you remember where you were when you heard Gordon Brown’s Gillian Duffy gaffe on the campaign trail in April 2010 (above), and how you heard it?

You may well have been tipped off to the then prime minister’s "bigoted woman" slip-up on Twitter or Facebook. Mark Frankel remembers it well: “The Gillian Duffy timeline was so visceral, so fast, but the social media aspect was still limited back then. Now we’d have Memes, Vines, Sub-reddits and metrics on trends… How do we capture all of that?”

With fellow News:rewired panellists from the Guardian, BuzzFeed UK and Trinity Mirror, the BBC’s assistant editor for social news was exercised by the challenges to come. Frankel didn’t exactly say 'where do I start?', but he didn’t hold back.

For instance, do you become part of someone’s campaign if you report the seismic social disruption behind, say, a ‘Gillian Duffy moment’?

The parties will be tweeting like mad, and tweeting a lot more sophisticated infographics. Should BBC News, for instance, be publishing those on its website? And, if not, how can it make visually engaging, shareable content from what the parties are putting out?

Even the BBC won’t be able to live-tweet every press conference, for each party, so there’s another balancing act. Should newsdesks be ignoring social media endorsements by celebrities?

Is there a conflict between reporting the campaign on social media versus producing shareable content? Or between analysing how candidates are using social media (followers, keywords, retweets) versus reporting what they actually say?

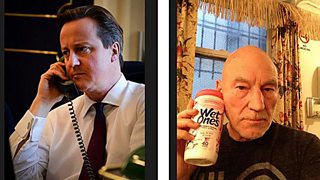

What if a big subject such as health is the topic of the day but a great political gag (like Patrick Stewart’s tweeted imitation of David Cameron’s call to Barack Obama, above) is going viral? How much do you focus on the NHS that day?

And if politicians are more focused on Twitter and Facebook but the younger, 'hard to reach' electorate are more likely to be on Instagram or WhatsApp, what's the best way of engaging them - say, with a Q&A - while not ignoring your sizeable followers and fans on other platforms?

Finally, in the midst of all the chatter, what do you just decide to stop doing before you run out of resources? Frankel’s view was that these are all “live issues” which BBC News and others would need to address in the course of the campaign, with the aim of “finding the balance between what’s shareable and what’s important”.

Over to the Guardian’s data editor, Alberto Nardelli, who anticipated an election where there would be access to more data than ever before and, through platforms like Twitter, greater access to experts and fact-checkers.

There lay opportunities and pitfalls. While it was easier than ever before to share flawed information - including on vote-swinging issues like immigration - social media was an instant way to engage with trusted experts, make politicians more accountable and correct inaccurate data in real time.

There was also a reminder from the Guardian man that shed loads of numbers competing for attention in the new open space was of no use to journalists or voters unless they were not only wrangled but rooted in real lives. “Data without humanity is meaningless,” he said.

For BuzzFeed - one of the digital dynamos “stealing the lunch” of more traditional news outfits, according to conference keynote and Guardian exec Aron Pilhofer - election targets would be small, niche, madly shareable exclusives, and the really big stories with mass appeal “often funny, often shocking”. It wouldn’t be hitting the “middle ground where everyone else is”, explained BuzzFeed UK’s dynamic deputy editor Jim Waterson.

Two other key messages from him: “We’d never publish anything that doesn’t look great on a phone” (the website previews everything on a fake iPhone screen) and “UKIP generates astonishing traffic to BuzzFeed” (multimedia coverage of a UKIP carnival in Croydon last year got 200,000 views).

Sarah Lester, executive editor at the Manchester Evening News, rolled out a whole battery of social tactics that Trinity Mirror regional titles would be employing: from Google Hangouts between editors and readers to Facebook Q&As, digital hustings and a postcode-searchable, mobile-friendly ‘find my seat’ feature packed with constituency data on history, poverty statistics, demographics and more.

Live-blogging from counts would be the “bread and butter” of the group’s offer “but we’ll be asking ourselves if content is shareable before we create it,” she said.

And what if, come 8 May, there is an indecisive result? Journalists’ responsibility to cut through the noise would only intensify, Frankel argued, as official party statements fought for space with social media chatter from victorious and defeated candidates.

“There could be days of mindless speculation… We’d have to make it not mindless and explain where the discussions are going,” he said. And then, presumably, lie down in a darkened room.

The BBC’s draft editorial guidelines for the 7 May general election

BBC Trust consultation on draft guidelines closes on 11 February.