Change of shape

When a forceA push or a pull. The unit of force is the newton (N). acts on an object, the object may change shape by bending, stretching or compressing - or a combination of all three shape changes. However, there must be more than one force acting to change the shape of a stationary object in the following ways:

Pull an object's ends apart, eg when a rubber band is stretched.

Push an object's ends together, eg when an empty drink can is squashed.

Bend an object's ends past each other, eg when an archer pulls an arrow back against a bow.

A change in shape is called deformationChanging shape and/or size as a result of forces being applied.:

elasticElastic materials return to their original shape and size after being stretched or squashed. deformation is reversed when the force is removed - there is no permanent change in shape.

inelastic deformation is not fully reversed when the force is removed - there is a permanent change in shape.

A rubber band undergoes elastic deformation when stretched a little. A metal drink can undergoes inelastic deformation when it is squashed.

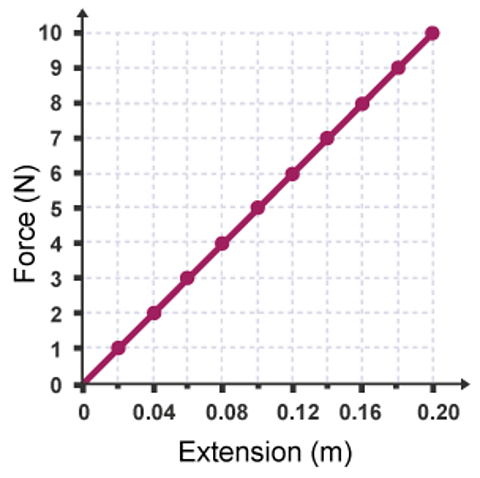

The force-extension graph

A force-extension graph can be used to calculate the work done in joules when stretching a spring.

In a force-extension graph:

the gradient is the spring constant

the area under the line is the work done in stretching the spring

Practical experiment- how forces affect the extension of a spring

There are different ways to investigate the relationship between force and extension on a spring. In this practical activity it is important to:

measure and record length accurately

measure and observe the effect of force on the extension of springs

collect the data required to plot a force-extension graph

Aim of the experiment

To investigate the relationship between force and extension on a spring.

Method

Secure a clamp stand to the bench using a G-clamp or a large mass on the base.

Use bosses to attach two clamps to the clamp stand.

Attach the spring to the top clamp, and a ruler to the bottom clamp.

Adjust the ruler so that it is vertical, and with its zero level with the top of the spring.

Measure and record the unloaded length of the spring. Remember to measure to the same point each time.

Hang a 100 g slotted mass carrier - weight 0.98 newtons (N) - from the spring. Measure and record the new length of the spring. Add a 100 g slotted mass to the carrier. Measure and record the new length of the spring.

To convert mass in grams to weight in newtons (\(N\)), you can use the formula \(W\) \(=\) \(mg\), where \(W\) is the weight in newtons, \(m\) is the mass in kilograms, and \(g\) is the gravitational field strength in newtons per kilogram.

Repeat step 6 until you have added a total of 1,000 g.

Results

Record your results in a suitable table.

| Force (N) | Length (mm) | Extension (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (unloaded) | 22 | 0 |

| 0.98 | 52 | 30 |

| 1.96 | 83 | 61 |

| … | … | … |

Analysis

For each result, calculate the extension: extension = length - unloaded length

Plot a line graph with extension on the vertical axis, and force on the horizontal axis. Draw a suitable line or curve of best fit.

Identify the range of force over which the extension of the spring is directly proportional to the weight hanging from it.

Evaluation

It is important to keep the ruler vertical. Suggest another way to improve the accuracy of the length measurements.

Hazards and control measures

| Hazard | Consequence | Control measures |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment falling off table | Heavy objects falling on feet - bruise/fracture | Use a G-clamp to secure the stand. |

| Sharp end of the spring recoiling if the spring breaks | Damage to eyes, cuts to skin | Wear eye protection. Support and gently lower masses whilst loading the spring. |

| Masses falling to floor if the spring fails | Heavy objects falling on feet - bruise/fracture | Gently lower load onto spring and step back. |

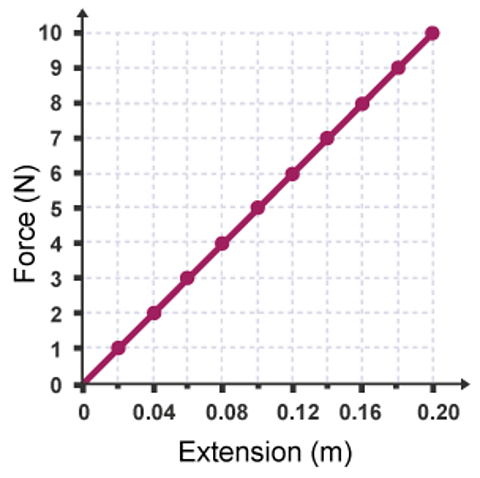

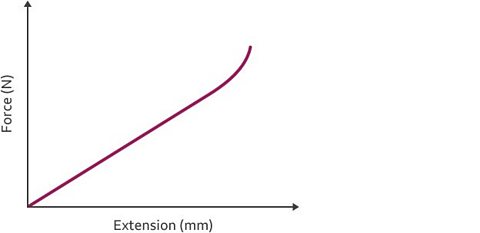

Extended syllabus content: Limit of proportionality

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about the term 'limit of proportionality' and to recall and use the spring constant as force per unit extension equation . Click 'show more' for this content:

Spring constant is a measure of the stiffness of a spring up to its limit of proportionalityThe point beyond which Hooke's law is no longer true when stretching a material.. The limit of proportionality refers to the point beyond which Hooke's law is no longer true when stretching a material.

The higher the spring constant, the stiffer the spring. The spring constant is different for different elastic objects. For a given spring and other elastic objects, the extension is directly proportionalA relationship between two variables, eg in a gas. As temperature increases, the pressure would also increase proportionally. (If the temperature doubled, the pressure would double). to the force applied. For example, if the force is doubled, the extension doubles. This works until the limit of proportionality is exceeded.

The elastic limit of a material is the furthest point it can be stretched or deformed while being able to return to its previous shape. When an elastic object is stretched beyond its elastic limit, the object does not return to its original length or shape when the force is removed. Once a material has gone past its elastic limit, its deformation is said to be inelastic.

In this instance, the relationship between force and extension changes from being linear, or directly proportional, to being non-linear.

Non-linear extension occurs more in some materials than others. Materials like clay or putty usually show non-linear extension.

Limit of proportionality in a graph

Linear extension and elastic deformation can be seen below the limit of proportionality.

Non-linear extension and inelastic deformation can be seen above the limit of proportionality. The limit of proportionality is also described as the 'elastic limit'. The gradient of a force-extension graph before the limit of proportionality is equal to the spring constant.

Extension and compression

Extension happens when an object increases in length, and compression happens when it decreases in length. The extension of an elastic object, such as a spring, is described by Hooke's law:

force = spring constant × extension

\(F = k~e\)

This is when:

force (F) is measured in newtons (N)

spring constant (k) is measured in newtons per metre (N/m)

extension (e), or increase in length, is measured in metres (m)

Example

A force of 3 N is applied to a spring. The spring stretches reversibly by 0.15 m - the fact that the string stretches reversibly means that it will go back to its normal shape after the force has been removed. Calculate the spring constant.

First rearrange \(F = k~e\) to find k:

\(K = \frac{F}{e}\)

Then calculate using the values in the question:

\(k = 3 \div 0.15\)

\(k = 20~N/m\)

Activity: Spring extension

This activity demonstrates what happens to springs when you add different weights, or change the strength of the spring.

Video: Hooke's Law

In this short video Professor Brian Cox highlights the effect of forces in changing the shape of an object. Hooke’s Law is described using the example of a spring.

Resultant forces

When two or more forces act on an object, the resultant force can be found by adding up the individual forces.

A box on a table

If the weight of the box (acting downwards) is 50 N and the normal reaction force (acting upwards) is 50 N, the forces are balanced. The resultant force is 0 N.

An object falling through the air

If the weight of the box (acting downwards) is 50 N and the air resistance (acting upwards) is 20 N, the forces are unbalanced. The resultant force is 30 N downwards.

Podcast: Forces and elasticity

In this episode, James Stewart and Ellie Hurer introduce forces and elastic potential. They also explain the key equations needed to understand the relationship between forces and extension.

ELLIE: Hello and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics podcast.

JAMES: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in physics and combined science. I'm James Stewart, I'm a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: I'm Ellie Hurer, a bioscience PhD researcher.

Before you listen, just a reminder that you can listen to the whole series or find an episode that you want to focus on. Whatever works for you.

JAMES: Okay, let's get started. Today we are going to be talking about forces and elasticity.

So, when you apply more than one force to a stationary object, it can either compress, stretch, or bend. And when something is stretched, compressed, or bent, there is always more than one force acting on it.

ELLIE: Imagine a spring. If you push both ends, it compresses. If you pull it from both sides, it stretches. And if you try to get the ends to meet, it bends.

JAMES: Exactly! And when you bend, stretch, or compress an object, you cause it to deform, which means changing its original form. And there's more than one type of deformity.

ELLIE: Right, so the first type is called elastic deformity. That's when it returns to its original shape once the force has been removed from it. For example, a spring usually bounces back after I push it down.

JAMES: Yep, and the other type is called inelastic deformity. That's when an object stays deformed even after you stop applying force to it.

ELLIE: For example, if you pull the ends of a spring really far apart so it breaks, then it won't go back to its original form.

JAMES: Wait Ellie, I've got a joke for you. What did the worker at the rubber band factory say when he was fired?

ELLIE: I have no idea.

JAMES: Oh snap. I think we're there. Are we there?

ELLIE: Dad joke! Okay, well, whether it's elastic or inelastic deformity, when you apply a force to an object, you can extend it. So let's move on to the next topic, extension.

JAMES: Extension is the way the length of an elastic object changes when you stretch or compress it.

ELLIE: The extension of a spring is directly proportional to the force you apply to it. Force is proportional to extension. That means that when you double the force, you double the extension. And if you half the force, you half the extension.

Another term for proportional you might hear is linear relationship, they mean the same thing. The extension has a linear relationship with the force.

JAMES: So force is proportional to extension until the object reaches its limit of proportionality, which is the maximum amount of force that can be applied to an object before it changes shape permanently.

ELLIE: When an object is elastically deformed and returns to its original form, there's a linear relationship between force and extension. That means, as force increases, extension also increases. If you pull the spring, so a pull force, the spring extends in length.

JAMES: Beyond this, when an object is inelastically deformed, there's a non-linear relationship between force and extension.

This basically means that as the force increases, the extension still increases. But a little bit slower, not at a proportional rate. And it might eventually stop increasing entirely if it has gotten as long as it can be. Now the equation we use to calculate that force is: force equals spring constant multiplied by extension.

The spring constant is a measure of the stiffness of a spring. Think of it like how much force has to be applied to make it stretch by a certain amount. And the units of spring constant are newtons per metre, or capital ‘N’ slash lowercase ‘m’.

ELLIE: So the higher the spring constant, the stiffer the object is because it needs more force to be applied to it in order to stretch.

JAMES: Yeah, we talked about work done in the last episode actually, which you can always go back and listen to. Ellie, how does that apply to elasticity?

ELLIE: When a force compresses or extends a spring, it does work and stores elastic potential energy in the spring. And if the spring hasn't been inelastically deformed, the work done on the spring will equal the amount of energy transferred into its elastic potential energy store.

JAMES: That was a mouthful, well done.

So how then do you calculate the work done on an elastic object? I'm going to keep testing you. How do you figure out how much elastic potential energy is stored in an object when you stretch or compress it?

ELLIE: With our final equation of the day, grab that pen and paper again, and let's write it out.

Elastic potential energy equals 0.5 multiplied by the spring constant, multiplied by extension squared. So let me repeat that again. Elastic potential energy equals 0.5 multiplied by the spring constant, multiplied by extension squared. Oh, that was a mouthful.

JAMES: You’ve earned a day off after that. Shall we do that as a real-world example? This might make it a little bit easier. So, again, pen and paper if you want to write this one out.

If a spring had the spring constant of three newtons per metre, and it was stretched until extended by 0.4 metres, you would square the extension of 0.4, then multiply this by the spring constant of 3. And then multiply this by 0.5 to get an answer of 0.24 joules.

ELLIE: Wow, that's definitely something that needs to be written down.

JAMES: Thank you, yep. Put that on a t shirt.

ELLIE: So, I hope this helped everyone listening to better understand elasticity.

JAMES: And I think you should have a prize for saying elasticity 17,000 times.

ELLIE: Thank you.

JAMES: Yep. Let's recap the three points. The main things that we covered in today's episode. There are two types of deformation. Elastic and inelastic deformation.

Elastic deformation is when the object goes back to its original shape when the force is removed. And inelastic deformation is when it changes shape permanently. Now, the equation to calculate force in a spring is force equals spring constant multiplied by extension. And finally, the equation to calculate elastic potential energy, is elastic potential energy equals 0.5 multiplied by spring constant, multiplied by extension squared.

ELLIE: Smashed it, James.

That's the key points you need to know about elasticity. In the next episode of BBC Bitesize, we're going to dig into displacement, distance and speed.

JAMES: Oh, they're hard words, just keep on coming, don't they? Thank you for listening to Bitesize Physics. If you found this helpful, and I hope you did, please do go back and listen again, and make some notes, and always come back here as many times as you want to help you revise.

ELLIE: There's also lots more resources available on the BBC Bitesize website, so be sure to check it out.

JAMES: One, two, three.

BOTH: Bye!

Newton's First Law

According to Newton's First Law of motion, an object remains in the same state of motion unless a resultant force acts on it. If the resultant force on an object is zero, this means:

a stationary object stays stationary

a moving object continues to move at the same velocityThe speed of an object in a particular direction. (at the same speed and in the same direction)

Examples of objects with uniform motion

Newton's First Law can be used to explain the movement of objects travelling with uniform motion (constant velocity). For example, when a car travels at a constant speed, the driving force from the engine is balanced by resistive forces such as air resistance and friction in the car's moving parts. The resultant force on the car is zero.

Other examples include:

a runner at their top speed experiences the same air resistance as their thrustA force used to move a body forwards or up, eg the rocket had a thrust of 10,000 N.

an object falling at terminal velocity experiences the same air resistance as its weight

Examples of objects with non-uniform motion

Newton's First Law can also be used to explain the movement of objects travelling with non-uniform motion. This includes situations when the speed, the direction, or both change. For example, when a car accelerates, the driving force from the engine is greater than the resistive forces. The resultant force is not zero.

Other examples include:

at the start of their run, a runner experiences less air resistance than their thrust, so they accelerate

an object that begins to fall experiences less air resistance than its weight, so it accelerates

Extended syllabus content: F = ma equation

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to recall and use the equation F = ma. Click 'show more' for this content:

Newton's Second Law

Force, mass and acceleration

Newton's Second Law of motion can be described by this equation:

resultant force = mass × acceleration

\(F = m~a\)

This is when:

force (F) is measured in newtons (N)

mass (m) is measured in kilograms (kg)

acceleration (a) is measured in metres per second squared (m/s²)

The equation shows that the acceleration of an object is:

proportional to the resultant force on the object

inversely proportional to the mass of the object

In other words, the acceleration of an object increases if the resultant force on it increases, and decreases if the mass of the object increases.

Example

Calculate the force needed to accelerate a 22 kg cheetah at 15 m/s².

\(F = m~a\)

\(F = 22 \times 15\)

\(F = 330~N\)

Extended syllabus content: Motion in a circular motion

If you are studying the Extended syllabus content, you will also need to describe motion in a circular motion. Click 'show more' for this content:

The relationship between force, radius and speed can be shown the using the equation \(F\) \(=\) \(mv\)2 / \(r\) (you do not need to recall this equation or be able to use it but it is an effective way to remember the relationship).

From this relationship we can summarise that;

when mass and radius are constant, if the speed of rotation increases, the centripetal forceForce, needed for circular motion, which acts towards the centre of a circle. must also increase.

when mass and speed of rotation are constant, if the radius of motion is decreased, the centripetal force must increase.

if we increase the mass of the object in circular motion, to keep a constant speed and radius, the centripetal force must be increased.

Friction

frictionA force that opposes or prevents movement and converts kinetic energy into heat. is a contact forceA force exerted between two objects when they are touching.. These are forceA push or a pull. The unit of force is the newton (N). that act between two objects that are physically touching each other. Examples of other contact forces include reaction forceAn object at rest on a surface experiences reaction force. For example, a book on a table. and tensionAn object that is being stretched experiences a tension force. For example, a cable holding a ceiling lamp..

When a contact force acts between two objects, both objects experience the same size force, but in opposite directions. This is Newton's Third Law of Motion.

Solid friction

Two solid objects sliding past each other experience solid frictionThe force between two touching objects that are moving or trying to move. It impedes motion and produces heating. forces. For example, a box sliding down a slope.

Solid friction forces on two objects always act in the opposite directions to their overall movement.

Solid friction forces can slow objects down and change their direction. They can also produce heat when the Kinetic energyEnergy which an object possesses by being in motion. store in the objects is being transferred to their internal energy storeThe total kinetic energy and potential energy of the particles in an object. store. For example, the friction between a match and its box produces enough heat to light it, or rubbing your hands together on a cold day.

Frictional forces are often useful. For example, people can walk because of frictional forces between their shoes and the pavement. Frictional forces also allow cars to accelerate, brake and turn corners.

Some frictional forces are not useful. For example, parts of car engines that touch produce friction which can generate heat and wear them away. Here friction is often reduced by using lubricationApplying a slippery substance to two surfaces to reduce friction. Oil is a common lubricant which is applied to moving parts in machines, like the chain and gears on a bike. like engine oil.

Without a force propelling an object it will gradually stop because of frictional forces. This is Newton’s First Law of motion.

Drag

Drag is the frictional force that acts upon an object as it moves through a gas or liquid. air resistanceA force of friction produced when an object moves through the air. is a type of drag which occurs when an object moves through air. For example, a skydiver falling from a plane.

A skydiver will slow when they open their parachute. This increases their surface area and so increases drag which slows them down.

More drag occurs when objects are moving at higher speeds. A submarine has more drag to work against when it is moving more quickly. The same is true for a car and air resistance. Keeping at these higher speeds requires more energy from the engines.

The effects of drag can be minimised by streamlining moving objects. Formula 1 teams make cars with minimal drag to increase their speeds.

Turning off the engine stops the forward force. Without this the vehicle (or other object) would gradually stop because of drag. This is unless it was in space where there is no drag.

Video: Friction

Moments

A force or system of forces may cause an object to turn. A momentA turning effect of a force. is the turning effect of a force. Moments act about a point in a clockwise or anticlockwise direction. The point chosen could be any point on the object, but the pivotA point around which something can rotate or turn. - also known as the fulcrum - is usually chosen.

Using moments

Spanners and levers both use moments.

Spanners

Spanners are used to turn nuts and bolts. If you need to undo a nut that is very tight, you can:

- use a short spanner and apply a large force

or

- use a long spanner and apply a small force

Using the longer spanner increases the distance from the pivot. This reduces the amount of force needed to undo the nut from the bolt.

Levers

Removing the lid from a can of paint requires a large lifting force on the lid. A screwdriver acts as a lever.

The pivot is the edge of the can and this is very close to where the strong push is needed to lift the lid to open the can.

A screwdriver with a long handle means that you can push down on the handle of the screwdriver with a small force and still open the can.

Calculating the moment of a force

The magnitude of a moment can be calculated using the equation:

moment of a force = force × distance

\(M = F~d\)

This is when:

moment (M) is measured in newton-metres (Nm)

force (F) is measured in newtons (N)

distance (d) is measured in metres (m)

Key fact: it is important to remember that the distance (d) is the perpendicular distance from the pivot to the line of action of the force (see diagram).

Example

A force of 15 N is applied to a door handle, 12 cm from the pivot. Calculate the moment of the force.

First convert centimetres into metres:

12 cm = 12 ÷ 100 = 0.12 m

Then calculate using the values given in the question:

\(M = F~d\)

\(M = 15 \times 0.12\)

\(M = 1.8~Nm\)

Question

A force of 40 N is applied to a spanner to turn a nut. The perpendicular distance is 30 cm. Calculate the moment of the force.

\(M = F~d\)

\(30~cm = 0.30~m\)

\(M = 40 \times 0.30\)

\(M = 12~Nm\)

Moments and balanced objects

If an object is balanced, the total clockwise moment about a pivot is equal to the total anticlockwise moment about that pivot.

Key fact: if the object is balanced: total clockwise moment = total anticlockwise moment

The diagrams show two examples of balanced objects where there is no rotation.

For a balanced object, you can calculate:

the size of a force, or

the perpendicular distance of a force from the pivot

Example

A parent and child are at opposite ends of a playground see-saw. The parent weighs 750 N and the child weighs 250 N. The child sits 2.4 m from the pivot. Calculate the distance the parent must sit from the pivot for the see-saw to be balanced.

child's moment = force × distance

250 N × 2.4 M = 600 Nm

Parent's moment = child's moment

Rearrange \(M = F~d\) to find d for the parent:

\(d = \frac{M}{F}\)

Then calculate using the values:

\(d = \frac{600~Nm}{750~N}\)

\(d = 0.8~m\)

Extended syllabus content: Applying the principle of moments

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to be able to apply the principle of moments to other situations. You will also need to describe an experiment to demonstrate that there is no resultant moment on an object in equilibrium. Click 'show more' to see this content.

Moments with multiple forces

Moments with multiple forces on one side of the pivot are calculated using the same equation as before:

Moment of a force = force × distance

M = F d

This is when:

moment (M) is measured in newton-metres (Nm)

force (F) is measured in newtons (N)

distance (d) is measured in metres (m)

If there is more than one force on one side of the pivot, each moment is calculated separated and then added together.

Example

An adult is sitting on one side of a seesaw. Their weight is 600 N and they are 1.5 m from the pivot. Their moment is therefore:

\(M = F d\)

\(M = 600\) × \(1.5\)

\(M = 900 Nm\)

Two children are sitting on the other side. The first has a weight of 200 N and is 1 m from the pivot. Their moment is therefore:

\(M = F d\)

\(M = 300\) × \(1\)

\(M = 300 Nm\)

The second child has a weight of 400 N and is 1.5 m from the pivot. Their moment is therefore:

\(M = F d\)

\(M = 400\) × \(1.5\)

\(M = 600 Nm\)

The combined moment of both children is:

\(300 Nm + 600 Nm = 900 Nm\)

The seesaw is therefore balanced because both moments are equal.

Moments experiment

A scientific experiment can show that there is no overall (or resultant) moment on an object in equilibrium.

Apparatus

A uniform metre rule, retort stand, boss and clamp, two 100g mass hangers and twelve 100g slotted masses, a g-clamp, three lengths of string.

Method

Suspend the metre rule at the 50 cm mark so that it is balanced horizontally. The ruler is said to be in equilibrium. The 50 cm mark is the pivot.

Suspend a mass, m1, from one side of the ruler a distance, d1, from the pivot. Read the distance d1 in cm, from m1 to the pivot. Record in a suitable table. Record the value of mass m1 in kg in the table too.

Suspend a second mass, m2, from the other side of the pivot. Carefully move this mass backwards and forwards until the ruler is once more balanced horizontally. Read the distance d2 in cm from the mass m2 to the pivot. Record d2 in cm, in the table, along with the mass m2 in kg.

Repeat several times using different masses and distances.

Calculate the turning forces, F1 and F2, using W = mg.

Calculate the clockwise and anticlockwise moments.

Safety

Clamp the retort stand to the bench with the g-clamp to it doesn’t fall and hurt someone or fall on their feet.

Place an obstacle, such as a stool, to keep feet from beneath the metre rule, to make sure the mass hangers don’t fall on someone’s foot.

Safety glasses should be worn in case the meter rule swings and hits someone in the eye.

Results

For ANTICLOCKWISE moment:

| Mass m1 in kg | Turning force F1 in N | Perpendicular distance from the pivot d1 in cm | Anti- clockwise Moment in Ncm |

|---|---|---|---|

For CLOCKWISE moment:

| Mass m2 in kg | Turning force F2 in N | Perpendicular distance from the pivot d2 in cm | Clockwise Moment in Ncm |

|---|---|---|---|

Conclusion

Each time the ruler balances horizontally we can see from the results that the anticlockwise moment about the pivot is equal to the clockwise moment about the pivot. This proves that there is no resultant moment on an object in equilibrium.

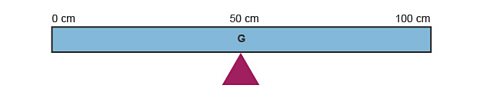

Centre of gravity

Position

Depending on the object's shape, its centre of gravity can be inside or outside.

Regular shapes

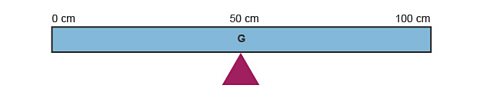

A metre rule is a uniform and regular shape, therefore its centre of gravity, G, is at its centre ie, at the 50 cm mark.

The metre rule balances freely at its centre of gravity.

Position of centre of gravity (G)

Regular shapes - A metre rule is uniform and a regular shape, therefore its centre of gravity, G, is at its centre - ie, at the 50cm mark. The metre rule balances freely at its centre of gravity.

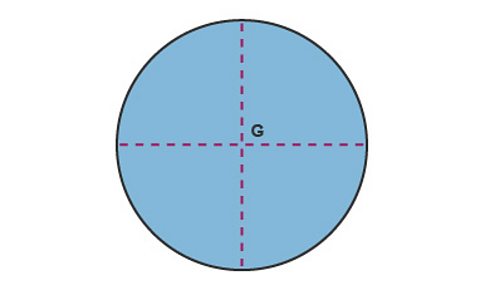

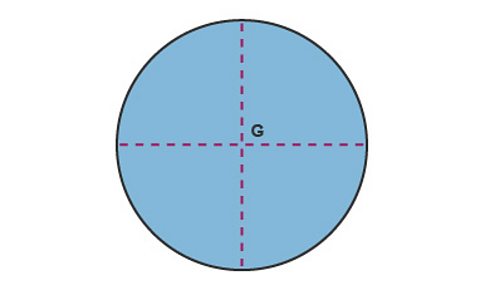

Disc

The centre of gravity G is the centre of the circle, where the diameters cross.

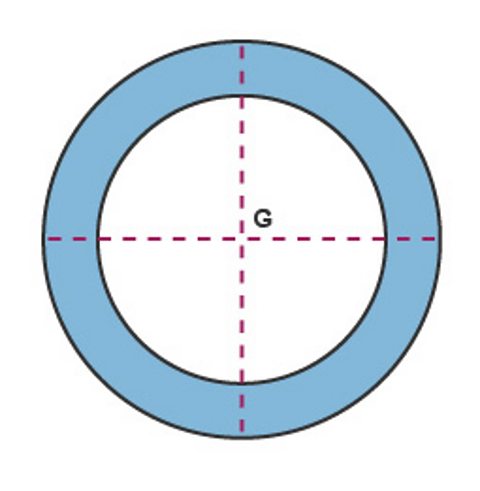

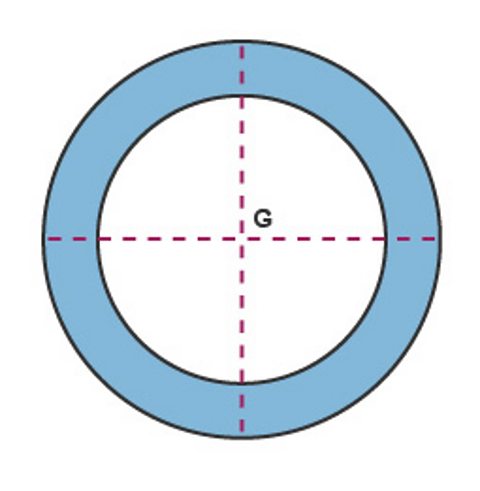

Ring

The centre of gravity, G, is at the centre of the ring, where the diameters cross. In this case, the centre of gravity is not part of the ring but in the space at the centre.

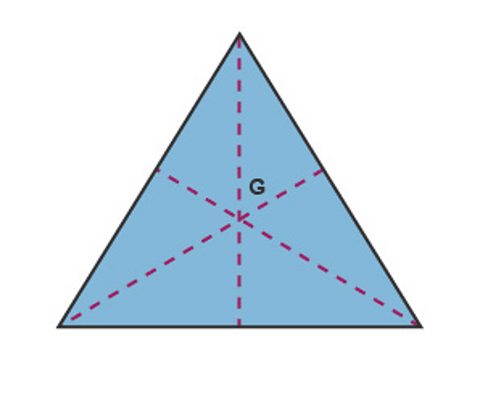

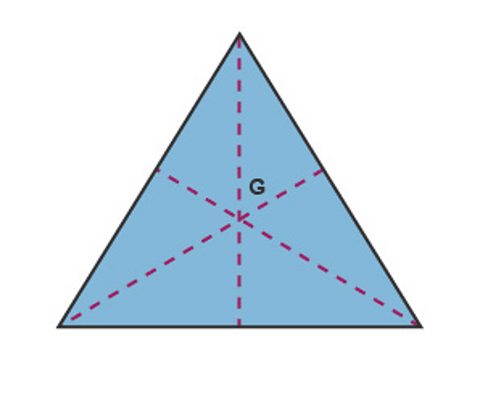

Irregular shapes

The centre of gravity, G, is where the medians cross. It is closer to the base than the top, because there is more weight towards the base.

Non-uniform

A hockey stick is non-uniform - it is thicker and heavier on one end. Its centre of gravity, G, is not at its centre but will be closer to the heavier, curved end.

Finding the centre of gravity

A flat shape is called plane laminaA flat shape. A simple experiment can be used to find the centre of gravityThe centre of an object from which the force of gravity acts. of a plane lamina.

Equipment: Plane lamina, plumb lineA length of string with a mass tied to one end. A plumb line is used to find the centre of gravity of an object. , pencil

Method:

A small hole is made at the top of the plane lamina.

The plane lamina is hung from this hole to allow it to pivotA point around which something can rotate or turn..

The plumb line is also hung from here and will fall vertically downwards.

A dotted line is draw along the plumb line to the mass.

The second hole can be made anywhere close to the edge of the shape and does not specifically need to be at the bottom.

The above steps are repeated.

The centre of gravity is where the lines cross.

Stability

Stability is a measure of how likely it is for an object to topple over when pushed or moved.

Stable objects are very difficult to topple over, while unstable objects topple over very easily.

Key fact: an object will topple over if its centre of gravity is 'outside' the base, or edge, on which it balances.

Key fact: for an object to be stable it must have:

a wide base

a low centre of gravity

Objects with a wide base, and a low centre of gravity, are more stable than those with a narrow base and a high centre of gravity.

The yellow car has a wider wheel base and lower centre of gravity than the blue car.

It is more stable.

The wheel acts as the pivotA point around which something can rotate or turn. for the car.

The weight has a turning effect or moment, which causes the car to topple over or fall back.

A double decker bus is stable as it has a:

low centre of gravity because of its low, heavy engine and heavy bottom deck;

wide wheel base.

A traffic cone is stable as it has a:

low centre of gravity G because of its heavy base;

wide base.

Quiz

Test your knowledge with this quiz on forces.

Teaching resources

Are you a physics teacher looking for more resources? Share this selection of short videos with your students:

More on Motion, forces and energy

Find out more by working through a topic

- count6 of 11

- count7 of 11

- count8 of 11

- count9 of 11