Using standard units

Length, time and volume are all examples of quantityA property that can exist as a magnitude, usually with a numerical value. For example, speed (quantity) is measured in metres per second. that can be measured.

A unit of measurement is one unit of a quantity: for example, one second.

Standard units of measurement are the units most typically used to measure a quantity.

Units of length and time

Units of length

Kilometres (km) and miles are the standard units used to measure long distances.

Smaller lengths are measured in metres (m), centimetres (cm) or millimetres (mm).

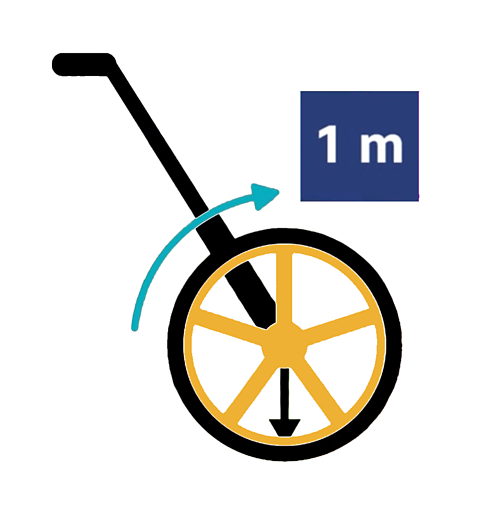

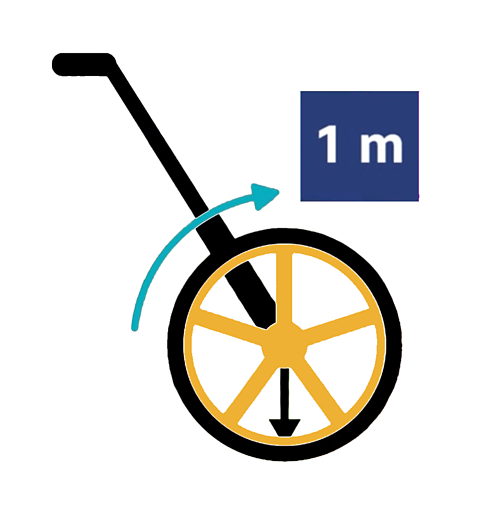

Shorter distances can be measured with a ruler or tape measure. Longer distances can be measured using a measuring wheelA wheel that is pushed along the floor and rotates once every metre that is used to measure longer distances.. Each time the wheel rotates it travels one metre.

Units of time

Time has various units of measurement, eg seconds, minutes, hours, days and years. Clocks or stopwatches can be used to measure the amount of time something lasts - for example, how long it takes an athlete to complete a race in an event or training.

Clocks and timers have different levels of accuracy:

- Sun dials cast a shadow to give a rough indication of the time of day

- pendulum clocks rely upon the swinging of a mass and are more accurate than sundials

- atomic clocks are the most accurate

Average values

Some distances and times are short, such as the swing of a pendulum of a clock or the test for reaction times. When measuring these it is more precise to take multiple readings and calculate an average.

The mean is a measure of average. To find the mean of a list of numbers, add them all together and divide by how many numbers there are:

\(\text{mean} = \frac{\text{sum of all the numbers}}{\text{amount of numbers}}\)

Units of area and volume

The area of a 2D shape is the amount of space inside it.

Area can be measured in square kilometres (km2), square metres (m2), square centimetres (cm2) and square millimetres (mm2).

Volume measures the space inside a 3D (three-dimensional)An object with width, height and depth, eg a cube. object. The standard units of volume are cubic metres (m3), cubic centimetres (cm3) and cubic millimetres (mm3).

Capacity measures the amount that a 3D object can hold. The standard units of capacity are litres (l) and millilitres (ml).

Measuring cylinders can be used to measure the volume of liquids. To ensure an accurate result, use a measuring cylinder only a little larger than the volume.

They can also be used to measure the volume of solids when used with a displacement canA piece of equipment to measure the volume of an irregular solid. The can is filled with water up to a narrow spout and the solid placed in the can. The water displaced through the spout is collected and its volume measured - this is equal to the volume of the solid.. The solid is lowered into the can and the volume of water that is pushed out into the measuring cylinder is the same as the volume of the object.

Example

A gold bar is a cuboid measuring 5 cm by 10 cm by 8 cm. It is melted down and made into cubes with edges of length 2 cm. How many cubes can be made?

The volume of the cuboid is: \(5 \times 10 \times 8 = 400~\text{cm}^\text{3}\)

The volume of one cube is: \(2 \times 2 \times 2 = 8~\text{cm}^\text{3}\)

The number of cubes = \(\frac{\text{volume of the large cuboid}}{\text{volume of one cube}}\)

The number of cubes = \(\frac{400}{8} = 50\)

50 cubes can be made.

Converting units of area

The unit conversions for length can be used to calculate areas in different units.

The two squares have the same area.

Square 1

Area = \(1~\text{m} \times 1~\text{m}\)

Area = 1 m2

Square 2

Area = \(100~\text{cm} \times 100~\text{cm}\)

Area = 10,000 cm2

Since square 1 and square 2 have the same area, \(1~m^2 = 10,000~cm^2\)

Use the same method to convert cm2 into mm2.

Square 3

Area = \(1~\text{cm} \times 1~\text{cm}\)

Area = 1 cm2

Square 4

Area = \(10~\text{mm} \times 10~\text{mm}\)

Area = 100 mm2

Since square 3 and square 4 have the same area, \(1~cm^2 = 100~mm^2\)

Example

Convert 5.2 m2 into cm2.

1 m2 = 10,000 cm2

So, \(5.2~\text{m}^2 = 5.2 \times 10,000 = 52,000~\text{cm}^2\)

Converting units of volume

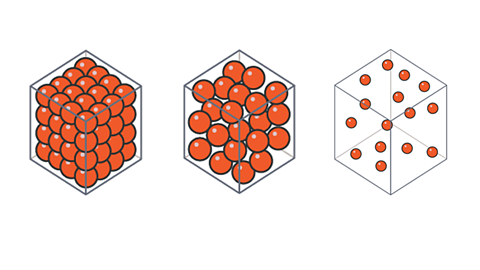

The two cubes have the same volume.

Cube 1

Volume = \(1~\text{m} \times 1~\text{m} \times 1~\text{m}\)

Volume = 1 m3

Cube 2

Volume = \(100~\text{cm} \times 100~\text{cm} \times 100~\text{cm}\)

Volume = 1,000,000 cm3

Since cube 1 and cube 2 have the same volume, \(1~\text{m}^3 = 1,000,000 ~\text{cm}^3\)

The same method can be used to convert cm3 into mm3.

Cube 3

Volume = \(1~\text{cm} \times 1~\text{cm} \times 1~\text{cm}\)

Volume = 1 cm3

Cube 4

Volume = \(10~\text{mm} \times 10~\text{mm} \times 10~\text{mm}\)

Volume = 1,000 mm3

Since cube 3 and cube 4 have the same volume, \(1~\text{cm}^3 = 1,000 ~\text{mm}^3\)

Some example metric unit conversions for volume are:

- 1 m3 = 1,000,000 cm3

- 1 cm3 = 1,000 mm3

- 1 litre = 1,000 ml

Example

Convert 25,000 cm3 into m3.

\(1~\text{m}^\text{3} = 1,000,000~\text{cm}^\text{3}\)

So, \(25,000~\text{cm}^\text{3} = 25,000 \div 1,000,000~\text{m}^\text{3} = 0.025 ~\text{m}^\text{3}\)

Scalar quantities

Extended syllabus content: Scalar quantities

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about scalar quantities. Click 'show more' for this content:

A physical quantity is something that can be measured. Scalar quantities only have a magnitudeThe size of a physical quantity., or size.

Examples of scalar quantities

Some examples of scalar quantities include:

- temperature, eg 10 degrees Celsius (°C)

- mass, eg 5 kilograms (kg)

- energy, eg 2,000 joules (J)

- distance, eg 19 metres (m)

- speed, eg 8 metres per second (m/s)

- time, eg 15 seconds

Adding scalars

The sum of scalar quantities can be found by adding their values together.

Example

Calculate the total mass of a 75 kg climber carrying a 15 kg backpack.

75 kg + 15 kg = 90 kg

Subtracting scalars

Scalar quantities can be subtracted by subtracting one value from another.

Example

A room is heated from 12°C to 21°C using a radiator. Calculate the increase in temperature.

21°C - 12°C = 9°C

Vector quantities

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about vector quantities and calculations. If you are studying the Core syllabus, go straight to the quiz:

Vector quantities have both magnitude and an associated direction. This makes them different from scalar quantities, which just have magnitude.

Vector examples

Some examples of vector quantities include:

- force, eg 20 newtons (N) to the left

- weight, eg 600 Newtons downwards

- velocity, eg 11 metres per second (m/s) upwards

- acceleration, eg 9.8 metres per second squared (m/s²) downwards

- momentum, eg 250 kilogram metres per second (kg m/s) south west

- electric field strength, eg 7 V/m from positive to negative

- gravitational field strength, eg 9.8 N/kg downwards.

The direction of a vector can be given in a written description, or drawn as an arrow. The length of an arrow represents the magnitude of the quantity. The diagrams show three examples of vectors, drawn to different scales.

Calculations involving forces and velocities

The resultant forceThe single force that could replace all the forces acting on an object, found by adding these together. If all the forces are balanced, the resultant force is zero. is a single force that has the same effect as two or more forces acting together. You can easily calculate the resultant force of two forces that act in a straight line.

Two forces in the same direction

Two forces that act in the same direction produce a resultant force that is greater than either individual force. Simply add the magnitudes of the two forces together.

Example

Two forces, 3 newtons (N) and 2 N, act to the right. Calculate the resultant force.

3 N + 2 N = 5 N to the right

Two forces in opposite directions

Two forces that act in opposite directions produce a resultant force that is smaller than the combined forces. It is often easiest to subtract the magnitude of the smaller force from the magnitude of the larger force.

Example

A force of 5 N acts to the right, and a force of 3 N act to the left. Calculate the resultant force.

5 N - 3 N = 2 N to the right

Resultant velocity

The same principle applies with velocities. The resultant velocityThe overall velocity acting upon an object. is a single velocity that has the same effect as two or more velocities acting together. You can easily calculate the resultant velocity of two velocities that act in a straight line or opposite to each other.

Example

Calculate the resultant velocity from +5 m/s and -1 m/s.

5 -1 = +4 m/s

Free body diagrams and vector diagrams

Free body diagrams are used to describe situations where several forces act on an object. Vector diagrams are used to resolve (break down) a single force into two forces acting at right angles to each other.

Forces and velocities at right angles

In the following diagram of a toy trailer, when a child pulls on the handle, some of the 5 Newton (N) force pulls the trailer upwards away from the ground and some of the force pulls it to the right.

Vector diagrams can be used to resolve the pulling force into a horizontal component acting to the right and a vertical component acting upwards.

Vector diagrams

Draw a right-angled triangle to scale, in which each side represents a force. Try to choose a simple scale, for example 1 cm = 1 N. For the toy trailer example above, draw:

- a line representing the 5 N force at 37°

- a horizontal line ending directly below the end the first line

- a vertical line between ends of the two lines

- arrow heads to show the direction in which each force acts

Measure the lengths of the horizontal and vertical lines. Use the scale for the first line to convert these lengths to the corresponding forces.

The two component forces together have the same effect as the single force (in this example, the child's pulling force).

The same applies with velocities. You can draw vector diagrams for these too.

Podcast: Scalar and vector quantities, contact and non-contact forces

Measurements can be split into two groups - scalar quantities and vector quantities. In this episode, James Stewart and Ellie Hurer break down the key facts about quantities and contact and non-contact forces.

JAMES: Hello, and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics podcast.

ELLIE: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in physics and combined science.

JAMES: I'm James Stewart. I'm a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: And I'm Ellie Hurer, a bioscience PhD researcher.

JAMES: We are going to be your guides. We're going to cover everything from forces to electricity, energy to gravity. We are going to explore some of the fun and complex parts of physics to help you revise.

ELLIE: And if you want to really get into it, be sure to grab a pen and paper, so you can make notes and try out equations throughout the whole episode.

JAMES: Absolutely, this is episode one of our eight-part series all about forces! So let's begin.

ELLIE: When it comes to physics, we're often measuring things we can and can't see, like weight, direction, and speed.

JAMES: And the types of things we measure can be split into two groups. So we have scalar quantities and vector quantities.

ELLIE: Okay, so what makes a quantity scalar or vector?

JAMES: Well, it's kind of in the name. Let's start with scalar quantities, which, as you might have guessed, sounds a bit like the word scale.

ELLIE: A scalar quantity is a physical quantity that only has a magnitude. The word magnitude means size, so examples of scalar quantities are mass and distance.

JAMES: Okay, so if you were to ask me how fast I drove my car here this morning, right, I would say 30 miles per hour. Or if you asked me how much pasta I was having for lunch later, I would say 50 grams of pasta. Is that right?

ELLIE: Exactly. A car's speed and the mass of pasta just have a magnitude. So they're scalar quantities because we just measure them with numbers.

JAMES: What's a vector quantity then?

ELLIE: Well, a vector quantity is something we measure with both magnitude and direction, like weight and displacement.

JAMES: Okay, so if I walked to the skate park and it was 2km to the east of my house, let's say, would that be a vector quantity?

ELLIE: Exactly, because there you're measuring displacement, so both the direction and distance.

JAMES: Okay, so another example would be diving, I don't know, five metres down into a swimming pool.

ELLIE: Yep, that's right, because you're talking about both a magnitude, five metres, and a direction downwards.

JAMES: Good. Okay, right, time to get your pen and paper out. Now, we want you to write down your own vector quantity, something that has both a direction and a magnitude. Now, remember that the word magnitude simply means size.

ELLIE: Like swimming 10 metres to the left or pushing 7 Newtons to the right or driving 20 miles per hour to the north.

JAMES: Ellie, this whole series is all about forces, so what is a force? Is that a scalar quantity or a vector quantity?

ELLIE: Drumroll, please? Force is a vector quantity because it has both a magnitude and direction. A force is a push or pull that can change the position, speed or state of an object. A force occurs due to an object interacting with another object.

JAMES: And we measure those forces in Newtons. The sign for that is an uppercase ‘N’.

ELLIE: Exactly. Forces are vector quantities that are measured in Newtons and have a direction. So if you pushed a shopping trolley, you could say you pushed it 4 Newtons to the left.

JAMES: Yeah, and there are two different types of forces, aren't there?

ELLIE: Yeah, so there's contact forces and non-contact forces. So let's dig into the differences between them.

JAMES: Contact forces are forces that occur when the objects physically touch. For example, friction, air resistance and tension. Now one key thing to know about contact force is that when an object at rest exerts a force on the surface it's placed on, there's a reaction force that acts at right angles to the surface.

This is what we call a normal contact force. For example, a book on a table exerts a force down on the table, and the table exerts a normal contact force of the same size back up on the book.

ELLIE: Whereas, non-contact forces are forces that act between objects that aren't physically touching. For example, electrostatic force, magnetic force and gravitational force, which we'll hear more about in future episodes.

JAMES: Yes, we will look forward to that. But before we go, we're not quite finished yet. Let's do a quick summary of where we've got to so far, what we've learned. I think that's a good time to do that.

- Number one, magnitude simply means size despite the complicated word.

- Number two, scalar quantities just measure magnitude, whereas vector quantities measure magnitude and direction.

- Three, forces are vector quantities.

- And four, finally, there are both contact and non-contact forces.

ELLIE: That's great, James. And thank you everyone for listening to Bitesize Physics. If you found this helpful, go back and listen again and make some notes so you can come back to them when you revise.

JAMES: Yeah, great idea. And in the next episode of Bitesize Physics, we are going to focus on one particular force. Gravity. Be sure to tune in then.

ELLIE: I can’t wait. And until then, may the force be with you.

JAMES: See you next time. Bye!

Quiz

Test your knowledge on scalar and vector quantities with this quiz.

More on Motion, forces and energy

Find out more by working through a topic

- count2 of 11

- count3 of 11

- count4 of 11

- count5 of 11