Section 2: Bright and dark craters

There are thousands of lunar craters that can be seen and enjoyed with a telescope.

But some are prominent enough to be seen by smaller instruments such as binoculars. As the phase of the Moon changes throughout the month, the variation in lighting of these features makes them even more exciting to watch.

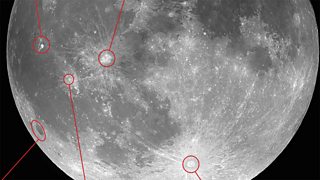

As we are intending this as an introduction to the Moon, the craters we have chosen here shouldn’t be too hard to spot and will stand out under most phases, especially those close to full Moon.

Bright Craters

Aristarchus:

Let’s start with Aristarchus, the brightest feature on the Earth-facing side of the Moon. Its brilliance is due to the fact that the impact that created Aristarchus was quite recent in lunar terms. The crater is estimated to have been formed within the last billion years or so.

Aristarchus also stands out because it’s located in the darker surroundings of Oceanus Procellarum.

The bright crater itself should be fairly easy to pick out with a pair of binoculars. A telescope will show it as a small 24 mile diameter depression. A lovely sinuous valley, known as the Vallis Schroter, can also be seen nearby if you’re using a telescope.

Keplar and Copernicus:

Not too far from Aristarchus lie two distinct ray craters known as Kepler and Copernicus. Their impressive ray systems result from material thrown up from the impacts that created both craters.

Kepler itself is fairly small at just 20 miles across but its appearance under high illumination (that’s when the 'terminator' is a long way away) is obvious thanks to the rays pointing back towards it.

Copernicus is larger with a diameter of 56 miles and this makes it easier to see. Binoculars should show both ray systems with ease. Through a telescope, Copernicus offers lots of detail including terraced walls and three central mountain peaks which formed as part of the impact process that created the main crater.

Tycho:

Without doubt, the most impressive ray crater that we can see from Earth is Tycho. The crater itself is about 50 miles across but its rays spread for almost the diameter of the Moon. See if you can trace the one that crosses the Mare Serenitatis (which you now know about thanks to Section 1!).

Proclus:

Another smaller but still quite prominent crater lies to the southwest of the Mare Crisium. This is best seen when the illumination is high. A bright region with noticeable straight edges is associated with the ray crater Proclus.

Despite being small at just 17 miles across, the Proclus region actually stands out really well next to the sea.

Look for the two distinct edges that mark the southern edges of the ejecta blanket (the name given to the spread of material ejected when the main crater was formed).

That is a whole collection of bright craters which are easy to see under high illumination, close to when the Moon is full, but there are some good dark ones visible too. Craters which are bright under high sunlight tend to be newish features, typically less than a billion years in age.

The bright material which is brought up during the impact coats them and their immediate surroundings with highly reflective material which fades in time.

Dark Craters

Dark craters are typically older and have floors which resemble tiny seas. This is due to them being filled with dark lava which has solidified as a relatively smooth layer. Over time, further impacts occur which pit the lava resulting in tiny craterlets.

Plato:

The dark plain to the north of Mare Imbrium is a 61 mile diameter crater known as Plato. It’s a very distinctive feature which can be seen with binoculars. If you have a telescope and the lighting is oblique (from the side, as is the case when the terminator is nearby), many tiny craterlets can be picked out on its otherwise smooth looking floor.

Grimaldi:

The crater Grimaldi, at 134 miles across, is over twice the size of Plato and being dark and fairly large, almost resembles a mini-sea close to the western edge of the Moon.

Visibility: A pair of binoculars is the minimum requirement to see these features.

When: Look for them close to when the Moon’s phase is full.

See also

Other sections

![]()

Section 1: The lunar seas

You only need to use your eyes for this section

![]()

Section 3: Craters in Shadow

You will need to use binoculars for this section

![]()

Section 4: Majestic mountains

You will need to use a telescope for this section

![]()

Section 5: Lunar specials

You will need to use a telescope for this section