Did Shakespeare visit Bristol in 1597?

By Sally-Beth MacLean, General Editor, Records of Early English Drama

In 1531, Bristol was the third largest city in England, both in terms of wealth and population.

A great overseas trading port on the River Severn, Bristol was clearly a mecca for touring entertainers – it hosted one of the country’s six great annual fairs at St James’ tide in late July, and over 100 performing troupes are known to have visited the city.

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Bristol

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

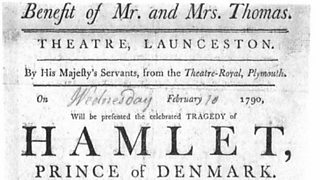

Shakespeare's likely visit to the Guildhall (Image credit: Bristol Record Office)

BBC Radio Bristol's Emily Chiswell finds out more about the trip to Bristol

How do we know this? Well from 1531 powerful people in cities like Bristol, such as the Mayors, started to keep a record of those who were paid to perform.

These records show that Shakespeare most likely made the trip to Bristol in 1597 with the company of actors for whom he both wrote and performed. The touring company was patronised by the Lord Chamberlain, and they played in the Guildhall before the mayor for a generous reward of 30 shillings in the week of 11-17 September, 1597, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

By 1597, Chamberlain’s Men had many of Shakespeare’s history plays in their repertoire, including Richard II, as well as three other recent works, Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Any of these might have been mounted in Bristol’s spacious hall (a late 18th century ground plan of the Guildhall notes the dimension of 100 feet from the back of the hall to the front of Small Street.)

In 1603, when King James came to power, Shakespeare’s troupe were given the royal seal of approval, and became officially known as ‘The King’s Men’.

Perhaps surprisingly, the King’s Men are recorded to have visited Bristol only twice, long after Shakespeare’s death. First in 1630 (sometime between 26 March-24 June) and the year following (between 25 June-29 September) when they were paid £2 to leave town, the same amount as the performance reward in the previous year.

Shakespeare mentioned Bristol in his play, Richard II

‘An offer, uncle, that we will accept:

But we must win your Grace to go with us

To Bristol Castle; which they say is held

By Bushy, Bagot, and their complices,

The caterpillars of the commonwealth,

Which I have sworn to weed and pluck away.’

(Henry Bolingbroke in Richard II, Act II Sc. 3)

Why were Shakespeare’s actors paid not to play in Bristol?

By Alan Somerset, Professor Emeritus, University of Western Ontario

Bans on travelling players didn't happen frequently, but they did happen…

Sometimes bans were "blanket" - that is, playing was simply forbidden anywhere in a town.

Word would get around among the travelling troupes that a ban was in place, so the troupes would simply go elsewhere, somewhere where there would be a welcome.

Sometimes a restriction would be put on playing in, say, the town hall, or a prohibition against any town funds being spent on playing. Then the players could play in another venue, such as an inn.

Even in Stratford-upon-Avon (Shakespeare’s home town of course) they banned the use of town funds for performances, and any part of the Guildhall buildings or grounds, though this would not prevent players from setting up in an inn.

Why did these bans happen, in whatever form we find them? There are a number of ostensible reasons, such as town poverty (as happened in Bridgnorth) or fear of the spread of plague. But behind many of them was an unspoken motive: Puritanism. This was the reason behind events in Stratford, which had, at different times, markedly Puritan clergy.

The other thing about these bans was that they were by definition impermanent - a council, in any year, was free to amend or undo the decrees of a predecessor council. But in practice there was great continuity of personnel on councils from year to year, so changes might come about only slowly. Or a council might decide to make an exception.

It is also apparent that hostility to players became more widespread as time went on and Puritan sentiment became more widespread. Then came the Civil Wars, when Parliament banned playing altogether, everywhere...

Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

Where did the players perform in Bristol?

The late medieval Guildhall was located on the west side of Broad Street near St John's Gate. Fortunately some illustrations survive though the building was demolished in the mid-nineteenth century and replaced by a more lavish Victorian Gothic building, smaller by a third than the older hall.

An unpublished report by a Victorian visitor tells us something about the interior of the hall where numerous Elizabethan acting troupes performed before the mayor and council:

'On entering the hall the visitor is somewhat impressed by an idea of its antiquity, arising, in a great measure, from the character of its early Gothic and lofty roof, which from its high pitch, would indicate its erection before the end of the fifteenth century, after which period they were made considerably lower. The tie-beams are supported on rainbow arches, springing from corbels, representing the figure of an angel, with expanded wings, supporting a shield, an ornament in general use from the latter part of the fourteenth century to the early part of the sixteenth. The spaces between the rafters, now ceiled with plaster, were originally left open to the actual frame timbers, as was the case with the Norman roof'.

Related Links

![]()

Shakespeare Lives

The nation’s greatest performing arts institutions mark 400 years since the Bard's death

Shakespeare on Tour: Around Bristol

![]()

Bristol Theatre Royal keeps it in the family

The father and son making waves in Bristol

![]()

Bath's trailblazing Theatre Royal

18th century tourists flock to the city for bathing, culture, and the theatre

![]()

Bath proves popular on Shakespeare's South-West tour

Civic accounts show a high amount of performances in Bath

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

![]()

The 18th century impersonator who was 'the Jon Culshaw of his day'

The city gets its prestigious Theatre Royal

![]()

The Northampton Repertory Theatre

Pieces of history in Northampton

![]()

Drunken robbers threaten the leader of Shakespeare's players

As he collects admission money at the door!

![]()

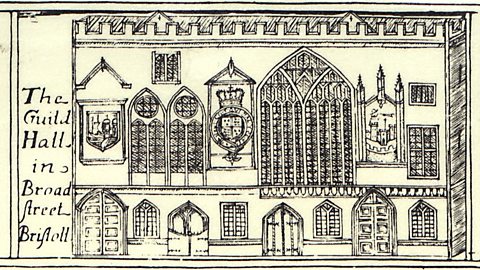

Shakespeare's tragic heroes appear in Launceston

Size not everything as Shakespeare's tragic heroes appear in remote town of Launceston