Bath's trailblazing Theatre Royal

In the 18th century Bath was one of the most fashionable places outside London. The royal family liked to go there to “take the waters” and soak up the city’s culture.

Those who flocked to the thermal spa for the sake of their health, also sought entertainment. In 1768 the theatre in Old Orchard Street was the first theatre in England outside London, to be granted a Royal Patent.

![]()

Much ado near me

Hear more Shakespeare stories on BBC Radio Bristol

![]()

Shakespeare Festival 2016

The BBC celebrates the genius of the bard

The “Theatre Royal” was permitted to stage plays, including Shakespeare, for as long a season as they wished.

Built in 1750, it was run by John Palmer (1742 – 1818) the son of a Bath brewer and theatre proprietor who became Mayor and a Member of Parliament for the city. He inherited the theatre.

Palmer claimed he had the best theatre and most intelligent audiences outside London

The Orchard Street theatre closed in 1805 and a new theatre was built in Beaufort Square in 1805, destroyed by fire in 1862 and then rebuilt in 1863 – this is the theatre building still in use today.

A second theatre, in Bristol, was opened in 1766 and granted Theatre Royal status in 1778.

According to Kathleen Barker in her prologue to The Theatre Royal Bristol 1766 – 1966, the original lessees were William Powell, John Arthur, Nathaniel Clark and a different John Palmer who was an actor.

Later on, John Palmer of Bath Theatre Royal was a lessee of the Bristol theatre from 1779 – 1817

The Bristol and Bath theatres shared one acting company, so actors travelled between the two theatres for engagements as well as shared stagehands, and scenery. So Palmer set up a coach service for his actors and materials to travel between the two locations. It was a practical solution; as a leading actor could rehearse in Bath in the morning, then travel by coach to Bristol for the evening performance.

To cover the 13 miles could take two to three hours by coach.

The first 'Theatre Royal' outside London

Theatre productions in the 18th and 19th centuries were highly regulated by government.

The regulation, which began in 1737 with the Licensing Act, was brought in by the then Prime Minister Robert Walpole, because his government had been subject to numerous satires on the London stage.

As a result the only way a venue could officially stage a play was if it had a patent. Given that only two patents had been issued – to Covent Garden and Drury Lane theatres in London – technically any productions outside these venues were illegal.

However, the groups of players who travelled the country to perform in the provinces generally avoided prosecution by local magistrates who were often fans of the theatre themselves.

Then in the later 18th century, provincial theatres started to be awarded ‘patents’, allowing them to take the name of Theatres Royal.

In 1788, restrictions were relaxed even more, meaning smaller towns which were not likely to gain a Theatre Royal were able to acquire an official licence from magistrates.

Such a licence could be issued for up to sixty days at a time, provided the location was not within twenty miles of London, eight miles of a patent or licensed theatre, fourteen miles from Oxford or Cambridge or ten miles from a Royal residence.

Bath though was ahead of the pack, acquiring a Theatre Royal Patent some ten years before Bristol.

The opening of the new Theatre Royal in Bath

In 1805 a new Theatre Royal was built in Beauford Square and opened its doors on 12 October 1805 with a production of Richard III. It was designed by George Dance, a professor of architecture at the Royal Academy. A different John Palmer – an architect - was also involved in the construction.

The licensee is named as Mrs Macready, who was the stepmother of the famous actor William Charles Macready.

The “stage-manager” is James Henry Chute, who eventually took over the management of the Bath and Bristol Theatres from his mother-in-law Mrs Macready.

He also held the lease for the Bath assembly rooms.

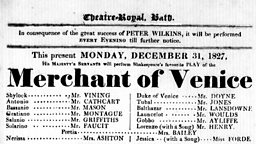

This playbill for “The Merchant of Venice” is dated 31 December 1827.

The play features the Jewish money-lender Shylock, who up until the first half of the 19th century had been depicted as either a villain or a clown.

But the famous actor Edmund Kean offered an alternative.

He presented a more sympathetic view of Shylock at Drury Lane, London on 26 January 1814, and audiences praised his performance.

From this point onwards, many actors played Shylock in a more human way, with his victimisation as the spark for his acts of vengeance.

Over a decade later Mr Vining’s performance of Shylock in Bath could well have followed this pattern.

However when he took on the role in London, audiences were lukewarm.

Let’s hope that two years later, the spectators in Bath were more enthusiastic.

The destruction and rebuilding of the Theatre Royal, Bath

There is still a theatre on the site where Shylock demanded his pound of flesh, although the building where this performance took place was destroyed by fire in 1862.

As the 19th century progressed declining ticket sales and audiences cast a shadow over the theatre’s future.

On the 18th of April 1862 it was destroyed by fire.

However Chute – the manager – asked the architect Charles J. Phipps to build a new theatre on the same site. It opened on the 14th of March 1863 with A Midsummer Night’s Dream and a farce, Marriage at Any Price.

Famous Bath-born theatre architect Charles J Phipps (1835 – 1897)

Phipps added a new entrance in Sawclose and this is where theatre-goers today gain access the building. Over the subsequent centuries the theatre has been repaired and refurbished and remains one of the oldest working theatres in the country.

The Theatre Royal, Bath was Phipps first major commission and he was engaged to provide a new theatre for Bristol too, the Park Row Theatre Royal, later the Prince’s Theatre. It cost £18,000 and seated 2154, which was 500 more than the old theatre.

As he grew older, Chute decided to concentrate on his Bristol theatre, but the end of his management career was marred by a tragedy. On the 26th of December 1869, 18 people were crushed to death at the Prince’s theatre.

Chute died at 2 Park Row Bristol, on July 1878.

Two of his sons followed him as partners in the management of the Bristol theatres.

About Shakespeare on Tour

From the moment they were written through to the present day, Shakespeare’s plays have continued to enthral and inspire audiences. They’ve been performed in venues big and small – including inns, private houses and emerging provincial theatres.

BBC English Regions is building a digital picture which tracks some of the many iconic moments across the country as we follow the ‘explosion’ in the performance of The Bard’s plays, from his own lifetime to recent times.

Drawing on fascinating new research from Records of Early English Drama (REED), plus the British Library's extensive collection of playbills, as well as expertise from De Montfort University and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Shakespeare on Tour is a unique timeline of iconic moments of those performances, starting with his own troupe of actors, to highlights from more recent times. Listen out for stories on Shakespeare’s legacy on your BBC Local Radio station from Monday 21 March, 2016.

You never know - you might find evidence of Shakespeare’s footsteps close to home…

Craig Henderson, BBC English Regions

A Thursday night with Sarah Siddons

Other fashionable amusements competed for the attention of these elite Bath audiences.

Thursday night was when the actress Sarah Siddons appeared in leading roles.

She worked hard for her £3 a week, a sum that was less than London wages, but quite usual for the provinces.

But she was put out to discover that her performances clashed with the popular Cotillion balls at the Assembly Rooms.

Eventually as her reputation spread, people gradually stopped attending these and went to see Siddons instead.

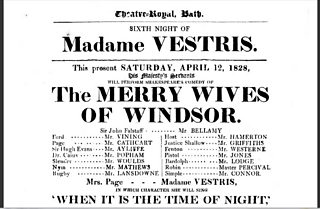

London star Madame Vestris plays in Bath

Madame Vestris was Lucia Elizabeth Mathews (1797-1856) a British actress, manager and business woman, who studied music and was noted for her voice and dancing ability.

Her exotic name was the legacy of a short marriage at the age of sixteen to a French dancer, who deserted her. However she kept her name throughout her career.

She played Rosaline at Covent Garden in the first-known production of Love's Labour's Lost since 1605.

More notably, in 1840 she staged one of the first productions of A Midsummer Night's Dream, which kept fairly true to the original text. She played Oberon, and started a tradition of female Oberons that lasted till around 1910.

In this 1828 production of The Merry Wives of Windsor in Bath she had the opportunity to demonstrate her fine contralto voice in the singing role of Mrs Page.

Related Links

![]()

Shakespeare Lives

The nation’s greatest performing arts institutions mark 400 years since the Bard's death

Shakespeare on Tour: Around Bristol

![]()

Bristol Theatre Royal keeps it in the family

The father and son making waves in Bristol

![]()

Did Shakespeare visit Bristol in 1597?

Civic accounts show a high amount of performances in Bath

![]()

Bath proves popular on Shakespeare's South-West tour

Civic accounts show a high amount of performances in Bath

Shakespeare on Tour: Around the country

![]()

Ipswich: a magnet for Shakespeare?

Why did Shakespeare's company visit Ipswich ten times?

![]()

Sarah Siddons visits Norwich

Putting the Theatre Royal, Norwich, on the map

![]()

Madame Tussaud's exhibiton in Nottingham

Including a model of William Shakespeare

![]()

Touring Kent to avoid the plague

In 1592, the plague forced touring theatre companies out of London