In 1881 the population of the village of Cilfynydd near Pontypridd stood at just 100 people. Then came the sinking of the Albion Colliery in the village and by 1891 it had risen to over 500. By 1901 the figure was approximately 3500.

This enormous population growth was typical of the Rhondda Valley in the nineteenth century but the 'coal rush' did not bring just increased prosperity and job opportunities – it also brought disaster and heartbreak on an enormous scale.

Albion Colliery stood on the old Ynyscaedudwg Farm and opened in August 1887. It had two 650-yard-deep shafts – one for going down, the other for coming back up. Two men had been killed during the sinking of the shafts but in seven years the pit had been relatively free of accidents. Within a few months an average of 17,000 tons of coal was being mined in what had become the largest single shaft winding colliery in south Wales. All that was to change on the afternoon of 23 June 1894.

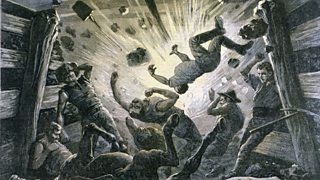

Firedamp explosion in mines of Anderlues, Belgium. Image: Roger Viollet/Getty Images

The night shift had just gone down, most of the men engaged in clearing dust and repairing the underground roadways. Then, in quick succession, came two loud bangs. Men standing on the surface by the entrance of the cage were blown backwards by the force of the explosion but although clouds of dust and smoke soon began to billow out of the shafts nobody reported seeing any flames or fire.

It was obvious that a major disaster had struck the Albion pit. When rescue teams went below there was some initial confusion as nobody knew exactly how many people had been working underground that day. However, it was later ascertained that 290 men and boys had been killed.

The bodies of the dead were so badly mutilated that it was almost impossible to identify casualties and there were several instances of families taking home bodies that later transpired had no relation to them at all. Very few miners managed to get out alive and most of those who did succumbed to their injuries within a day or so.

Everyone in the village lost someone they knew. One family lost 11 people, five family members and six lodgers. Of the 125 horses that were working underground that afternoon, only two survived.

The disaster was the worst mining tragedy to hit south Wales – an unenviable record that the pit held until the massive Senghenydd pit disaster of 1913. The cause of the explosion, it was decided, was the ignition of coal dust following an explosion of firedamp.

Regardless of the tragedy – and perhaps saying a great deal about the attitudes of the time – Albion Colliery was closed for only two weeks after the explosion. Soon it was back to normal with coal being hewn from the ground just as it had been for the previous seven years.

There was, of course, an enquiry into the disaster but the pit owners, the Albion Steam Coal Company, was exonerated from blame. In the words of the report:

'Such an occurrence was extraordinary and could not possibly have been anticipated by the management and we, therefore, have the greatest satisfaction in stating that no blame in the matter can be attributed to any of your officials or employees.'

Whether or not that conclusion was a 'whitewash' remains unclear. But for the families of the dead miners it could not have brought much comfort.

Albion Colliery later became part of the Powell Duffryn empire and remained operating when the mines were nationalised in 1947. The pit finally closed in 1966. When deep pit mining in Wales came to an end, the tragedy that occurred there in 1894 was still the second largest disaster in an industry that had a history of death and disaster. It was not the epitaph the miners of Albion Colliery would have wanted.