It's been a busy week on the programme, but I was struck by Lord Drayson's point that science may be too "elitist".

Science can certainly be hard - as I learnt trying to get my head round the basics of particle physics in the run up to the launch of the Large Hadron Collider last year.

Years ago I remember the neurologist turned arts impresario Sir Jonathan Miller admit that the ideas he'd had to grapple with as a scientist had "made his head hurt" in a way that the theatre never had, and it's true that the complexity of some ideas in science can act as a barrier making the subject fairly inaccessible.

But that's a very meritocratic kind of exclusivity....it doesn't matter where you were born, you just have to be clever.

Of course the point the science minister was making is about the image of science, and of scientists, as "nerdy" and somehow detached from everyday life. A government campaign to excite people about science and the opportunities it can create is surely welcome.

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

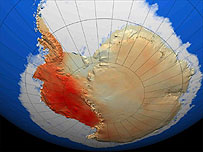

One area of science that doesn't need any help drumming up excitement is geo-engineering - the idea that we might solve global warming by managing the climate on a planetary scale.

A whole raft of apparently hair-brained schemes - from seeding the oceans with iron to building giant sun shades in space - have been suggested, but no one seems to know which ones might work or how much they'd cost.

Now scientists at the University of East Anglia have conducted the first comprehensive assessment of 20 of the leading geo-engineering solutions to climate change, trying to work out how much cooling you might get, and how feasible they really are.

It turns out that stratospheric aerosol injections - spraying sulphates into the upper atmosphere - has the greatest potential to cool the climate quickly, but doesn't address the longer term consequences of continuing to burn CO2. Professor Tim Lenton suggested that increasing the capacity of carbon sinks - locking greenhouse gases away in biomass or on the ocean floor - might be a better long term solution.

None of which will do anything to stem the decline of the honeybee.

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

Scientists remain baffled by the mysterious disappearing act of whole populations - named Colony Collapse Disorder in the US and Canada, and which now seems to have spread to Italy, France and Germany.

Here a succession of cold winters and wet summers has reduced honeybee numbers by about 30%, and even Jill Archer seems to be having trouble with the virtual bees of Ambridge.

But help may be at hand: Britain's biggest farmer, the Co-op, launched a ten-point rescue plan this week which included a ban on the use of eight neonicotinoid pesticides and £150,000 for research.

Interestingly the Co-op's Paul Monaghan told me they can't find any takers for the research money to investigate honeybee decline. So get busy with that grant proposal.

Well, now 82-year-old Sir David is back and - if anything - feistier than ever.

Well, now 82-year-old Sir David is back and - if anything - feistier than ever.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.