Long-form picks of 2013: Eating mice and stripping for Lindsay Lohan

Hugh Levinson

edits BBC Radio current affairs programmes, including Crossing Continents and From Our Own Correspondent

Nick Carr is not alone in arguing that we are actually engaged in a process of outsourcing our own memory, which means the little grey cells are at risk of atrophy.

He made the argument in - oh yes - a long-form article. And despite everything text-speak can throw at our collective intelligence, great long articles still seem to be appearing with startling and pleasing regularity. So here’s a personal selection of a few I’ve happened across this year which I think will be worth a few minutes of your time. They generally have more than 140 characters in them - actually, usually tens of thousands. Be warned.

I’ll start with one of those pieces that genuinely changes the way you look at the world. And it’s about jellyfish. “On the night of 10 December 1999, 40 million Filipinos suffered a sudden power blackout. President Joseph Estrada was unpopular, and many assumed that a coup was underway. Indeed, news reports around the world carried stories of Estrada’s fall. It was 24 hours before the real enemy was recognised: jellyfish. Fifty truckloads of the creatures had been sucked into the cooling system of a major coal-fired power plant, forcing an abrupt shutdown.”

Tim Flannery’s review of Stung! On Jellyfish Blooms and the Future of the Ocean by Lisa-ann Gershwin in the New York Review of Books has a similar shocker in almost every paragraph.

And, continuing with mind-blowing science, here’s a question: are plants intelligent? Michael Pollan, who’s one of my favourite writers, provides some thought-provoking answers in the New Yorker. “Plants have evolved between 15 and 20 distinct senses, including analogues of our five: smell and taste (they sense and respond to chemicals in the air or on their bodies); sight (they react differently to various wavelengths of light as well as to shadow); touch (a vine or a root ‘know’ when it encounters a solid object); and, it has been discovered, sound.”

For me, the mind-blowing stuff in this article came when Pollan discussed the evidence that plants communicate, citing the work of researcher Rich Karban. “When sagebrush leaves are clipped in the spring - simulating an insect attack that triggers the release of volatile chemicals - both the clipped plant and its unclipped neighbours suffer significantly less insect damage over the season. Karban believes that the plant is alerting all of its leaves to the presence of a pest, but its neighbours pick up the signal, too, and gird themselves against attack. ‘We think the sagebrush are basically eavesdropping on one another,’ Karban said.”

Plants may be more intelligent, or at least more caring, than some human beings. That might be one conclusion from a stunning investigative piece by Megan Twohey of Reuters who looked into what happened to foreign children adopted by US citizens once their new parents couldn’t cope. She discovered what she describes as: “America's underground market for adopted children, a loose Internet network where desperate parents seek new homes for kids they regret adopting… these children are often the casualties of international adoptions gone sour. Through Yahoo and Facebook groups, parents and others advertise the unwanted children and then pass them to strangers with little or no government scrutiny.”

Equally disturbing is one highlight from the ever-reliable Lunch with the FT feature. These are often lavish affairs with the pink’un treating titans of industry to stylish spreads. When David Pilling ate waffles in Seoul with Shin Dong-hyuk things were very different. Shin was both born in and spent most of his life in a North Korean prison labour camp. “I thought about food all the time. An hour after each meal, I was hungry again. There were lots of mice in the camp. We would ask the guard if we could catch them and, if he was in a good mood, he would say ‘OK’. Then the guard would watch us eat the mouse alive.” It’s no wonder that Shin tells Pilling: “I still think of freedom as roasted chicken.”

Mike Giglio told Suess’s story for BuzzFeed, describing how a man who considered himself 100% American found himself deported to Germany, unable to speak a word of the language and ending up in a shelter with others in the same fix. “Most of the Ausländer… seemed resigned to eking by on the government rolls and were already practiced at digging bottles from the trash at the end of the month. Even the blue-collar jobs many had held at home required, in Germany, special certification, via classes taught in the impossible native tongue, with its complex matrix of cases, declensions, and inverted syntax. (“I cross the street,” one complained. “How the fuck can the street cross me?”)

I’ll finish with some more fun stuff. In a shameless piece of self-promotion, check out Grayson Perry’s final Reith Lecture (which I, ahem, edited) for its eloquent and witty enquiry into what defines the artist: “Recently a friend told me that she was working on an education programme at the Whitechapel Art Gallery and at the beginning of the project she asked the children, she said, ‘What do you think a contemporary artist does?’ And this very precocious child, probably from sort of Muswell Hill or somewhere like that (LAUGHTER), she put her hand up and she said, ‘They sit around in Starbucks and eat organic salad.’ (LAUGHTER)… at the end of the project, she asked them again, ‘What now do you think an artist does?’ And the same child, she said, ‘They notice things.’ And I thought wow, that’s a really short, succinct definition of what an artist does. My job is to notice things that other people don’t notice.”

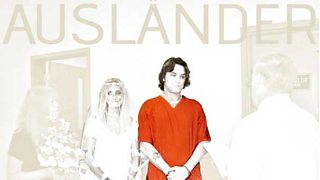

And for sheer entertainment the must-read of the year is Stephen Rodrick in the New York Times watching a valiant, doomed attempt by the screenwriter and director Paul Schrader to make a film with Lindsay Lohan (main image). Everyone tells him not to do it. And they are right. In one unforgettable scene, Schrader resorts to desperate measures in order to persuade Lohan to act. “Another hour passed, and Lohan eventually moved to the bed but wouldn’t remove her robe. Schrader worried that the early-morning sunlight would begin streaming through the house. He thought of sending everyone home. But then he realised that there was one thing he hadn’t yet tried. He stripped off all of his clothes. Naked, he walked toward Lohan. ‘Lins, I want you to be comfortable. C’mon, let’s do this.’”

Enjoy.

Bite-sized news versus long-form journalism: Make mine a Sicilian feast