Britain’s appetite for celebrity news: an effect of supply or demand?

Peter Kellner

is a journalist, political commentator, and President of YouGov. Twitter: @YouGov

A few weeks after I joined the Sunday Times in 1969 as a young graduate, the incomparable Nicholas Tomalin wrote his famous essay for the paper’s magazine about the trade of journalism. It is best remembered for its opening line: “The only qualities essential for real success in journalism are rat-like cunning, a plausible manner, and a little literary ability.”

However, to my mind, its most important passage comes later in his essay:

“A journalist’s real function, at any rate his required talent, is the creation of interest. A good journalist takes a dull, or specialist, or esoteric situation, and makes newspaper readers want to know about it. By doing so he both sells newspapers and educates people. It is a noble, dignified and useful calling.”

Those were the days: Insight’s memorable and important investigations for the Sunday Times; enquiring factual programmes in prime time on ITV, well-informed news features on serious subjects in the ‘Mirrorscope’ pages of the Daily Mirror.

Today a different impulse seems to dominate the media: give readers and viewers what they want. Many people deplore the showbiz obsessions of the Sun, and the populist agenda of the Daily Mail; but they sell far more copies than any other papers. They are clearly getting something right.

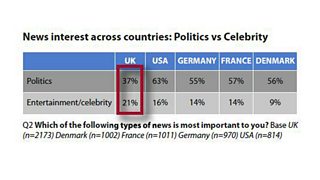

YouGov’s research for the Reuters Institute helps to explain what that something is, and how specifically British that something is. We offered people a list of different types of news story and asked them to identify which were most important to them. These are the proportions in five different countries saying ‘domestic political news’ and ‘entertainment and celebrity news’:

Poll: celebrity vs politics in the news

As these figures show, Britain is out of line with the other four countries. We are less interested in politics than they are, and more interested in celebrity news. If anything, the figures understate the propensity of the British to lap up celebrity stories: people tend to overstate their appetite for serious news, just as they often tell pollsters that their favourite TV programmes are nature documentaries, but the biggest audiences are for soaps, talent contests and reality shows.

There are two ways to view these findings. They tend to be advanced by opposing camps, but they are not strictly incompatible. Both may be valid. The first is that, in competing for readers and viewers, tabloid editors and TV executives are responding to public demand. The second is that, by packaging their papers and programmes in such a compelling way, these editors and executives are shaping that demand.

I believe both things are true. Readers and viewers who are passionate about politics and current affairs have plenty of choice – for example, in the pages of the Financial Times, Guardian and Economist, and by viewing BBC2, Channel 4 and the BBC’s Parliament channel. Add in what’s available on the internet and the public has vastly greater access to serious analysis and intense debate than ever before. So when most people prefer tabloid papers, soaps and reality shows it is not because they are starved of alternatives. It is because that is what they prefer.

On the other hand, supply does shape demand to some degree. Big Brother, Britain’s Got Talent and I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here did not erupt because market research showed a massive, unmet demand for these particular formats, but because programme-makers and TV executives judged that, with the right people, package and promotion, they could attract large audiences. To some degree, they generated the thirst they went on to slake. When Ant and Dec lured ‘celebrities’ into the wilder parts of Australia it was not because ITV responded to angry viewers demanding that former soap stars clamber through insect-infested plastic tubes.

My point is that far fewer resources are now devoted to any similar appetite-generation for serious journalism, on ITV or in mass-market newspapers. They have largely given up on Tomalin’s quest for compelling coverage of “a dull, or specialist, or esoteric situation”. Such investigations that are commissioned tend to have a simple and dramatic central message – for example, that particular MPs and peers fiddle their expenses, or that certain sports stars are corrupt, or that a university took money from a foreign dictator.

These are strong and important stories; but there are even more important issues that do not receive the treatment they deserve, or at least not until they become crises – and then they tend to be covered stridently and superficially. Britain and Europe’s current financial problems are a case in point. Where is the hour-long prime-time ITV special with the same resources and production values as the X Factor? Or the six pages in the Sun deploying the same flair that the paper devoted to serialising the biography of Simon Cowell?

To deplore this is not to appeal for an alternative diet of ‘good news’ stories that cheer us up. Journalists should report events and analyse issues on their merits. However, that is precisely what too many of them are NOT doing. Instead, much of their news agenda is driven, consciously or unconsciously, by a particular narrative. In the case of politicians, the prevailing narrative is that they are corrupt, remote, dishonest and malicious egomaniacs who evade straight questions and would sell their granny if this would advance their own career.

The Roman satiric poet Juvenal would have understood the forces at work. He described the concerns of citizens as “bread and circuses”. Alongside often simplistic ‘bread’ stories (for example, about house prices), today’s mass media pay inordinate attention to the ‘circuses’, alternating between relentless stories of real or imagined sleaze and the confected world of talent contests and reality shows. Without anyone asking for it, but with plenty of readers now paying for it, too many journalists now paint a bleak picture of Britain as a bizarre dystopia: not just a circus, but a circus noir.

This is the first of two extracts from Peter Kellner’s essay The Triumph and Perils of ‘Circus Noir’ Journalism, edited and reprinted with the kind permission of the author and YouGov. Thanks also to Nic Newman, editor of the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2012 in which the essay first appeared.