How many pieces to camera does a good documentary need?

Charles Miller

edits this blog. Twitter: @chblm

How many pieces to camera do you need in a presenter-led documentary?

I can’t remember anybody ever telling me, or even suggesting any kind of rule of thumb about it.

Sometimes, in a depressing viewing of an early cut, an exec producer will suggest that complicated sequences in the second half of the film could be helped along with a few simple, explanatory in-vision pieces. And that often turns out to be a good idea.

But otherwise, as a director, it seems to be up to you.

So my question is: does a good film gravitate to a certain rhythm, with the presenter doing what Americans call standups of a particular kind of duration at a particular sort of interval?

Kenneth Clark

If the first two represent the BBC’s current output, Civilisation is their revered ancestor. Clark’s delivery is magisterial (pronouncing ‘man’ with several syllables, more like ‘Mayan’) and the whole pace is different: the film begins with more than a minute and a half of organ music and not a word spoken before Clark strolls into shot.

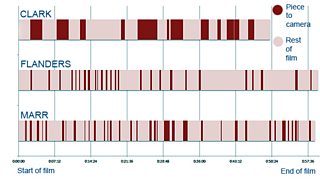

Here’s how the pieces to camera (in red) popped up in the timeline of the rest of the film (in pink):

Pieces to camera timeline

As you can see:

- Civilisation has far fewer, and much longer, pieces to camera than the two contemporary films

- The contemporary films are very similar in their patterns despite the fact that the Marr programme was a mainstream film for BBC1 while the Flanders was a comparatively esoteric subject for BBC2

- Perhaps there is one visible difference between Marr and Flanders in that the viewer sees more of Marr at the start and end of his film than of Flanders at the start and end of hers. In that sense, BBC1 seems to require a more obvious authorship from its presenters, setting up their subjects in a personal way and drawing the threads together at the end. There are also more pieces to camera by Marr than by Flanders.

Andrew Marr

But strangely, on the BBC at least, films themselves have gotlonger: subjects that would once have been commissioned at 40 or 50 minutes are now 60. That’s the result of a need to create ‘common junctions’ between channels. But it’s surely asking a lot of our twitchy, distractable audience to expect them to pay attention to a single subject for a whole hour. No wonder they increasingly have other screens on the go while they’re watching TV.

The numbers:

Average duration of pieces to camera:

Clark: 97 seconds

Flanders: 19 seconds

Marr: 19 seconds (yes, exactly, the same as Flanders).

Number of pieces to camera per film:

Clark: 12 (if this had been a 60-minute film, that figure, in proportion, would be 14.4)

Flanders: 26

Marr: 39.

Stephanie Flanders

It would also be interesting to know how many pieces to camera were actually recorded, and therefore how many never made it to the final film. I have always thought that filming pieces to camera is among the most efficient uses of time on location. You don’t want to end up with too many, but the strike rate in terms of finished duration in the final film is much higher than, say, the equivalent time spent doing interviews.

Footnote: how I measured the figures:

There was a certain amount of judgment needed, in that pieces to camera often start or end out of vision, and cut away to other shots in the middle too. In all cases, I tried to judge the start and end of the piece by guessing the ins and outs of the location sound - in other words, I am not ‘stopping’ my measurement when the editor has cut away from the presenter as long as it’s obvious that what we’re hearing is part of the in-vision piece.