Journalists who ‘harass’ eyewitnesses on social media risk public backlash

Alastair Reid

Managing editor of First Draft. Twitter: @ajreid

David Crunelle was standing in the departure hall at Brussels' Zaventem airport when the first bomb destroyed check-in row 11, some 20 metres away, on Tuesday 22 March. Seconds later, another bomb exploded to his left.

Dazed and dusty, he instinctively opened the camera app on his smartphone and began filming the chaos as he staggered out of the airport terminal. Once outside, he texted his family and sent a tweet.

An art director and photographer by trade, Crunelle continued to document the bloody scenes and survivors in the airport car park, posting images to Twitter.

Within 20 minutes of the explosion, his phone was ringing with calls from news organisations. By 10am, two hours after the bombs went off, he claimed to have received over 10,000 notifications from all manner of people. But one particular group stood out: journalists.

Eyewitnesses to breaking news events have always been the most important sources of information for reporters. Now, thanks to smartphones and social media, journalists can find and contact eyewitnesses within minutes – even seconds – of a bomb going off.

When the story is of global interest those requests can number in the hundreds. Of course, these are journalists just doing their job. But now social media users in general are kicking back, responding negatively when they observe the torrents of requests for contact.

I talked to two experts in eyewitness media, both of whom collaborate in the work of not-for-profit First Draft News, about that shift in public attitude and what the news media can do to address it.

Claire Wardle and Fergus Bell both had advice for journalists about behaving better towards first hand sources on social media, while playing the long game in getting access to the information and material only such sources can provide.

Remember, the witness may be in shock

"The speed at which journalists can contact eyewitnesses is so collapsed compared to previously," says Claire Wardle, research director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism and director of Eyewitness Media Hub (EMHub).

"That's the big shift and that's why there's the massive push back. Many eyewitnesses are still in shock and then they get a tweet from a journalist. And then they get a thousand."

"It looks like bombardment," agrees digital news and media consultant Fergus Bell. "It looks like potential harassment and you get a lot of people saying that it might be insensitive.”

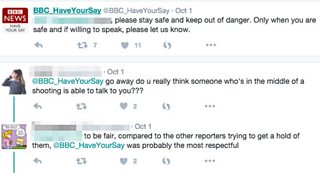

The Umpqua Community College shooting in October 2015 was a case in point. A witness faced similar circumstances to Crunelle after she tweeted about the attack. Journalists started contacting her for more information, including multiple reporters from the same organisations.

This eyewitness had hundreds of requests from journalists while the gunman was still at large.

And the public's response was fierce:

"We have to recognise the psychology of trauma, of what it feels like to be stuck in the middle of an event like this," argues Wardle.

“We've got this technological solution, which is the fact that you can find someone immediately and message them immediately, but very few people are ready to talk in that moment."

So how can journalists get the valuable information their audiences crave without being seen to be harassing eyewitnesses on social media? Wardle and Bell agreed that firing off a generic tweet and hoping for the best is not the most considered approach, especially if an eyewitness has already received dozens of similar requests and is not responding to any of them.

Some consideration for the situation an eyewitness may be in is vital, says Wardle. She’s "astounded", she says, that there aren’t already editorial guidelines which advise against contacting someone until an event is over, for fear of putting that person in danger.

Some Twitter users commended the BBC for how they handled a difficult situation

Talk off Twitter

The 140 characters that Twitter allows, with the world watching, is rarely going to be able to convey all of the information and nuance necessary in the circumstances.

Instead Wardle recommends trying to take the conversation away from Twitter. A little research can often turn up other social media accounts, an email address, a phone number or personal contacts of the source. This may be a more direct way of reaching someone, she adds, provided it is conducted with sympathy.

"Even if it's going in via a friend or a colleague to say 'this is a really important story, we really would like to talk to so and so, have you heard from them? Are they safe?’"

Copyright, conversations and chat apps

Copyright issues around newsworthy pictures from social media are a “time bomb" for news organisations, says Bell, because so many rely on a simple "yes" on Twitter and an onscreen credit as the legal basis to publish a picture or video.

"Just getting a Twitter permission means you have to monitor that Twitter feed forever more, in case they retract it. If they were to do that at any point in their entire lives using Twitter, then you're not allowed to use [the content] any more."

When trying to secure permission to use footage, always ask: “Did you take that?”, to avoid any potential copyright claims, Wardle adds. And try to get access to an original file of the imagery in order to verify it properly.

In the chaos of a breaking news situation, such requests and the legal jargon they often involve can seem callous. Engaging in a conversation instead may add much more to the story.

Some language used by journalists in breaking news can be confusing to eyewitnesses.

"If you actually work to contact that person and make sure the permission you get is through a personal exchange then you can also get their personal story," Bell points out, stressing the competitive advantage here.

"That is something that you won't get on social media and something that doesn't exist elsewhere. At the moment very few people are doing that."

And if a journalist is late in finding an eyewitness and their picture or video, they should have little hope the eyewitness will speak to them, Wardle warns. Instead, the witness’s other posts or mentions may give additional information as to their situation, story or contact details.

This eyewitness to the 2015 attacks in Tunisia gave additional information (highlighted in red) including his phone number, but journalists continued to ask for more on Instagram.

There are broader issues at play here too. The rise of chat apps and closed networks like WhatsApp and Snapchat, combined with the very public backlash against news organisations in breaking news situations, has meant many eyewitnesses first share their pictures privately.

If and when such pictures do emerge on public networks their origin is often lost to the digital ether, and with it the ability to trace any copyright claims or verification.

Ethics and the long game

"If we don't come across as more sensitive, even if that means taking a short term hit, we're definitely going to take the long term hit in getting access to this content," Bell believes. "We're already starting to see that with the rise of closed networks and the rise of people jumping in to advise individuals not to share with the media.

"Newsroom managers need to consider the long term impacts of the ways we're working and start to formulate better ones."

The social newsgathering ethics code published by the Online News Association (ONA), which Bell had a hand in formulating, addresses many of these questions, as does EMHub's guidelines for journalists, with which Wardle was involved.

However, neither fully addresses the issue at an industry level. Notions around pooling newsworthy content in breaking news; of collaborations between organisations; of involving social media networks in finding a solution have all been suggested but so far remain elusive.

In the meantime, reporters should try to speak to sources found through social media in the same way they would eyewitnesses in real life, Wardle says. "Always be polite, supportive and, if they're not ready to talk, say 'I completely understand, if you change your mind I'm still here'."

"You still have to consider if somebody is safe, and you need to make sure you're not commissioning more content."

When faced with the deluge of requests he received around the Brussels attacks, David Crunelle responded to as many journalists as he could. The eyewitness to the UCC shooting responded to none.

Both came away with differing opinions of the news organisations which contacted them, as did those members of the audience which saw the very public exchanges on Twitter.

When so much effort goes into engaging audiences in news on social media it would be a shame to undermine those efforts by not addressing how to find it in the first place.

“Ultimately, there just isn't a solution yet,” says Bell, "but that doesn't mean we should not look for one, or start thinking about ways that we can improve this.”

First Draft, a non-profit initiative supported by Google News Labs, is a coalition of organisations sharing tips and training in how to discover, verify and publish eyewitness media for news. Both Fergus Bell and Claire Wardle are members of the First Draft coalition.

Our section on social media skills, including newsgathering and verification

Our eyewitness media blogs by Sam Dubberley

#Paris: UGC expertise can no longer be a niche newsroom skill

UGC: Source, check and stay on top of technology

David Crunelle: The art of being in the wrong place at the right time