How I joined the suffering people of Yemen to tell their story

Nawal al-Maghafi

BBC Arabic reporter @Nawalf

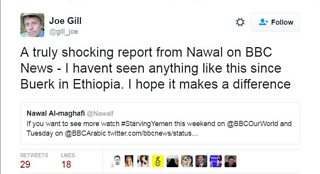

Nawal al-Maghafi’s harrowing BBC Our World documentary Starving Yemenand BBC News reports showing shocking evidence of severe, widespread malnutrition in her native Yemen have been compared to Michael Buerk’s reporting of the Ethiopian famine that jolted the world into action in 1984.

She and her Yemeni crew are among the very first journalists to expose a situation where more than 370,000 children are on the brink of starvation as a result of the 18 month-old civil war between a Saudi-led coalition and Houthi rebel groups.

We asked her how she made these unforgettable films, why this story has been so little reported until now and how the assignment has affected her as a Yemeni journalist:

How easy was it to travel into and around the country?

I’ve been going to Yemen to report for six or seven years. It’s a story very close to my heart. It used to be easy to get in and out but now, even as a Yemeni citizen, you have to apply to Saudi Arabia for an air ticket and get permission from the Houthi [rebel forces] to enter the country.

This time, I travelled with local cameraman Mohammed Al-Mikhlafi and a Yemeni, not a foreign crew, so I was able to blend in. Yes, we were stopped like all Yemenis are at Houthi-controlled checkpoints, but it would have been much more difficult for foreigners to move around.

Everywhere we went people were just so glad we had come to report on their situation. Even in a conservative society like Yemen, we were welcomed into the homes of people desperate to get their story out.

As one mother impressed upon us us, Yemenis too watch the news that’s dominated, night after night, by Syria. But their suffering - living under blockades that cut off their food supplies and air strikes that threaten their lives - is the same.

I’d flown in on a commercial flight, but during my three week stay the airports had been closed and the country was in lock down. The BBC had to arrange for me to be evacuated by the UN. There was no other way out.

When did you realise that the humanitarian situation in Yemen was more desperate than most people thought?

Yemen was always the poorest country in the Middle East but at least there were aid agencies on the ground and a tradition of people helping each other out. I’d last been in the major port city of Hudaydah, for instance, three years ago. When I went back this time, the aid agencies had pulled out. I’d never seen Yemenis left with no solutions, nothing left to share, nowhere to turn.

Our story was meant to be about the blockades and the politics but we never expected to witness what we did. The images of so many severely malnourished children were truly shocking.

What shocked you most?

The extent of the problem, certainly, but also the hopelessness. When we’d reported on the bombing before, there was always the expectation that it would eventually get better, people would rebuild. What I found particularly upsetting was the fact that a whole generation were facing the prospect of stunted growth through lack of food, no schools, no glimmer of hope left.

The vulnerability of the parents and carers - the middle classes and the poorest alike - was also difficult to deal with. We filmed a grandfather who had borrowed a lot of money to bring his desperately sick and starving four year-old grandson Shuaib from their remote village to Hudaydah for treatment (see top image). But even the central hospital there didn’t have the antibiotics he needed.

You have to think long and hard before showing a dying child. I know my voice was breaking as I reported that Shuaib had passed away but it was important to follow his story to the end. He represented so many others, as did the helplessness of his family.

It would be impossible not to be affected by what you saw. Were some stories harder to tell than others?

There was an acutely malnourished eight-year-old boy called Salem (pictured above) in the central hospital malnutrition ward. His own mother described him as “alive, but no longer here”. I have an eight-year-old brother and the comparison hit me hard.

But I think the plight of little Abdulrahman (below), an 18-month-old toddler in a remote village who was the size of a six month-old baby, that affected me more than anything. He was lactose-intolerant and, deprived of the special milk he needed, had been malnourished all of his life, unable to walk or talk.

I met Abdulrahman and his desperate mother through Yemeni doctor Ashwaq Muharram, who distributes medicine and food in and around Hudaydah out of her own pocket, using her car as a mobile clinic.

We followed her heroic search, over two weeks, to track down any supplies of the boy’s special milk. When she finally sourced some from her contacts in Saudi Arabia, we all broke down in tears. And he is only one of more than a million children affected.

Doctor Muharram was a central figure and access point in your documentary Starving Yemen. How did you meet her?

I first came across Ashwaq when I was researching the story. It was difficult because there were no NGOs on the ground. But I found this extraordinary woman who told me, before I arrived, how she had brought in medicines from Jordan to fight a recent outbreak of rabies.

She even invited me to go and live with her in Hudaydah during my trip. And when I fell ill with a fever, and had to stop filming for a day, she looked after me and got me the injections I needed to recover quickly.

Ashwaq took me from village to village with her as she visited the most vulnerable children. She gave me access to cases and stories I couldn’t have found any other way.

Doctor Ashwaq Muharram with eight-year-old Salem: "This is what famine looks like."

How close were you to the targets of coalition air strikes?

Bombing of the port in Hudaydah began the day after I arrived in the city, after a four-month ceasefire collapsed. I witnessed the aftermath of the bombing of an MSF (Medecins Sans Frontieres) hospital in Abs where 19 people died and a strike on a factory in Hudaydah which killed ten. It was relentless.

When you hear the planes up above there’s no escaping the dread of where the next airstrike will hit. It also means you get no sleep and the unpredictability means you don’t know where you’ll be able to go the next day.

Nawal al-Maghafi watches an airstrike on the port of Hudaydah from a rooftop in the city

Do you plan to go back?

Yes, soon. I want to follow up on the stories of the children we filmed, including a seven-month-old patient of Ashwaq’s called Fatima. She cried incessantly from hunger but her mother was too malnourished to breast-feed her baby. Because the bombing intensified towards the end of my time in the country, we never got to find out what happened to her.

Why has Yemen been such an under-reported story?

In terms of the international media, I think there is a lack of understanding about the country. Before the war in Syria, for instance, a fair number of people would have been on holiday there. Then Syria has hit home in other ways, including through the migrant crisis.

In Yemen the refugees are trapped. Three million people are internally displaced but the borders are closed and all visas were cancelled the day war broke out. It’s something of an unknown land and I fear it’s going to take the crisis there to come a lot closer to home for it to resonate in the West.

How difficult is it, as a Yemeni journalist, to cover this story?

Really quite tough. I feel as British as I do Yemeni. When I get back to London, having seen the destruction in Yemen, it makes me feel angry. It’s difficult to keep the barriers up because I’m part of the story. But when I’m reporting I make a conscious decision to take a step back.

Both sides in the conflict have been accused of atrocities. As a Yemeni journalist in particular, I feel a great responsibility to get out the voices of the people. Everyone listens to the politicians but we’ve not heard very much from the real victims in this war.

Has response to your Our World documentary and reports on BBC World News and domestic BBC network bulletins surprised you?

People see a lot of terrible pictures and there probably is a degree of desensitisation to suffering. But our pictures were shocking because they told a universal story that most people would relate to. That certainly was our aim.

Reaction on social media and through direct communication has been gratifying. We’re hearing that donations to aid appeals for Yemen peaked within minutes of the BBC News at Ten report. It’s been interesting this week to see a shift in the UK government’s stance on an independent inquiry into human rights abuses in Yemen. But it’s not for me to judge what the impact might be.