30 years after the Great Storm - how has weather forecasting changed?

Simon King

BBC weather presenter

The Great Storm of 1987 is a weather event many of us will have a memory of. You might have been directly impacted by the storm or you may just know about it from the infamous Michael Fish forecast. For me, it was much more. It was waking up in the early hours of the 16th October as a seven year old hearing the garden gate banging and the wind howling outside and the subsequent power cut that got me fascinated with the weather. It was this storm that planted the seed which grew into me being a weather presenter today.

You may not properly appreciate or notice but weather forecasts have improved significantly over the last thirty years. Accuracy in weather forecasts is currently improving at a rate of around one day per decade so the weather forecast in 1987 for 24 hours ahead has the same accuracy as a weather forecast four days ahead now.

A look at how raw data is turned into a weather forecast.

So how have things changed over the last 30 years?

With the increasing use and capability of satellite information along other weather data from around the world, there are now around 215 billion observations that go into the Met Office’s supercomputer. Having a good understanding of the current state of the atmosphere is really important before you can start predicting the atmosphere from and hour to days ahead.

Processing this number of observations and applying a lot of physics to model the behaviour of our complex atmosphere requires some serious computing power. Back in 1987, the supercomputer used to generate weather forecasts was about as powerful as a modern day smartphone (but much bigger). Today, our weather supercomputers used in the UK are amongst the most powerful in the world and are capable of doing over a quadrillion (that’s a number with fifteen zeros after it) calculations a second!

Peter Duben from the European Weather Centre talking about the numbers of the supercomputer.

Computer Knowledge

With more processing power, doing those calculations it may be no surprise that today our weather computer models are much higher resolution than they were in 1987, think a cathode ray tube TV from the 80’s compared to a 4k plasma TV now. We are able to represent mountains/coasts and urban areas much better which has an influence on conditions.

The number of models we have available has also changed. Three decades ago, the Met Office had 2 weather models; the course and fine resolution. We now have many more including the ensemble model from the European Centre of Medium Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF). This model is used by changing the initial conditions of the atmosphere by small amounts to produce 50 different outcomes. By looking at the spread in the forecast, we’re able to give a forecast some certainty. If all the ensembles are giving different scenarios, you may hear us saying that there’s some uncertainty in the forecast. If however, the ensembles come up with similar forecasts, there is good certainty.

David Richardson, Head of the Evaluation Section at ECMWF, explains ensembles.

Meteorological Knowledge

After studying the Great Storm, Meteorologists were able to pick out a small area of where we had some really violent, hurricane force winds in excess of 100mph. It was the sting in the tail of the storm and was coined as a ‘sting jet’. It might sound like something out of thunderbirds but we know have a much better understanding of these features and are now able to try to predict when then might happen in explosively developing storms.

Professor Peter Clark talks through the sting jet.

Warning System

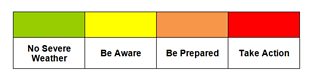

As a result of the Great Storm, the Met Office set up the National Severe Weather Warning Service in the UK, which was designed to warn contingency planners and the public of any impending severe weather. The system today is based on the likelihood of severe weather combined with the potential for impacts so you may hear a yellow ‘be aware, an amber ‘be prepared’ or a red ‘take action’ warning issued in areas depending on the severity of the weather expected. To compliment that, the Met Office now also name storms that might impact the UK or Ireland. This was an idea to increase awareness of the severe weather with people more likely to take action.