Electrical charges

All matter consists of atoms. Atoms contain three types of smaller particles: protonSubatomic particle with a positive charge and a relative mass of 1. The relative charge of a proton is +1., neutronUncharged subatomic particle, with a mass of 1 relative to a proton. The relative charge of a neutron is 0. and electronSubatomic particle, with a negative charge and a negligible mass relative to protons and neutrons.. Of these three, both the protons and electrons are charged.

Objects that are charged can affect other charged objects using the non-contact forceForce exerted between two objects, even when they are not touching, such as the force of gravity. of static electricityObjects that become positively charged or negatively charged, usually because of friction between insulators. .

Generally, the atom has a neutral charge, but if it loses an electron, it becomes positively charged and if the atom gains an electron, it becomes negatively charged. Charged atoms are called ions.

Key fact: Protons are positively charged. Electrons are negatively charged.

Objects that are charged can affect other charged objects using the non-contact forces of static electricity.

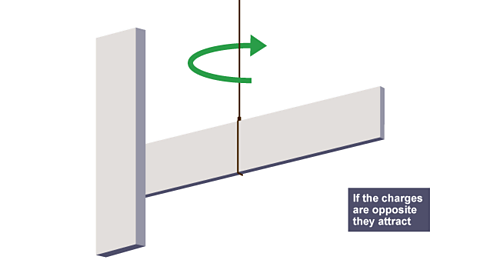

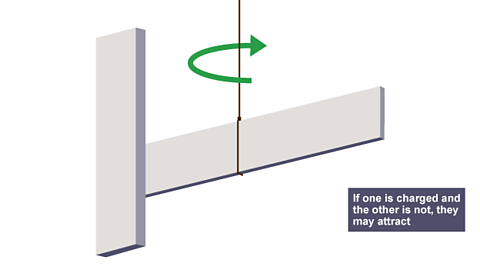

Positive charge repel other positive charges, negative charges repel other negative charges but positive and negative charges are attracted to each other.

Podcast: Static charge

In this episode, Ellie and James explore static charge, discuss how it's created, and share some of the key facts you need to know about attraction and repulsion.

JAMES: Hello and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics Podcast.

ELLIE: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in physics and combined science.

JAMES: I’m James Stewart, I’m a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: And I’m Ellie Hurer, a bioscience PhD researcher.

JAMES: And today we're going to be talking about static charge and how different objects repel and attract.

ELLIE: Well, I'm ecstatic to hear that. Let's begin.

JAMES: Have you ever taken a jumper out of the tumble dryer and felt a little electric shock when you've done it? Or maybe you've done that thing where you rub a balloon against your head to make your hair stand up in the air. If so, you've experienced something called static.

ELLIE: So static charge is an electric charge that accumulates on an insulated object, for example, because of friction. And just so you remember, something is insulated if it doesn't easily conduct electrical charge.

JAMES: Static charge occurs because the electrons are not free to move around in an insulator. So when they are transferred, they build up in one place. That's why we call it static charge. With static meaning stationary or simply can't move.

ELLIE: When certain insulating materials are rubbed against each other, for example, hair on a balloon, they become electrically charged.

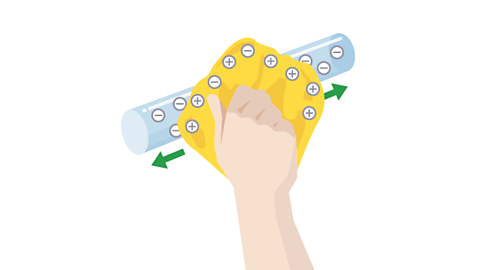

JAMES: Secondly, negatively charged electrons are rubbed off one material and on to another. The material that gains electrons becomes negatively charged, and the material that loses electrons is left with an equal positive charge.

ELLIE: So in the hair and balloon example, the balloon would gain electrons and become negatively charged, whereas your hair would lose electrons and become positively charged.

JAMES: Exactly, so when you move the balloon away from your hair, you'll find that the two insulating materials, the balloon and the hair, would actually attract each other, making your hair stand up as it reaches towards the balloon. And the two objects exert equal and opposite forces on each other, even though they're no longer touching.

ELLIE: You can see a similar effect when it comes to clothes that have come out of a tumble dryer. Sometimes you'll notice a spark between different jumpers, or feel a little shock maybe as static electricity is produced between them through friction.

JAMES: Yeah, let's talk about the science behind that, shall we? So as static charge builds up, the potential difference between an object and the Earth, or something connected to the Earth, gets bigger. Now, in this example, it's actually you who's connected to the Earth.

ELLIE: If this difference gets big enough, then the charge can jump across the gap and cause a spark. Though, this is usually quite small and just felt as a static shock.

JAMES: Another good example is when you jump on a trampoline.

When you jump up and down on the trampoline, charge builds up as you rub your feet on the bottom of the trampoline with each jump.

ELLIE: But then, when you reach out to help someone else onto the trampoline, the charge jumps from you to them, and it causes a static shock.

JAMES: In the case of static charge, opposites attract. This is why the negative and positively charged objects would attract each other.

ELLIE: But if you were to bring together two objects with a negative charge, they would repel each other. This type of attraction between oppositely charged objects is called electrostatic attraction.

JAMES: Attraction and repulsion between two charged objects are examples of a non-contact force. In case you forgot what that means, I'll quickly explain for you. A non-contact force is a type of force applied to an object by another object that's not in direct contact with it.

ELLIE: So, if you want to learn more about contact forces and non-contact forces, be sure to listen to episode one of our series on forces to find out more.

JAMES: Okay, let's recap the three key lessons we've learned here. So, firstly, when certain insulating materials are rubbed against each other, they become electrically charged. Now, that's what we call static charge.

Secondly, negatively charged electrons are rubbed off one material and on to another. The material that gains electrons becomes negatively charged. The material that loses electrons is left with an equal positive charge.

And finally, like charged objects repel, but oppositely charged objects attract.

ELLIE: Thank you for listening to BBC Bitesize Physics. If you have found this helpful, go back and listen again and make some notes so you can come back to this as you revise.

JAMES: There’s lots more resources available on the BBC Bitesize website, so be sure to check those out. In the next, and final, sadly, episode, we're going to be learning about the essentials of electric fields, so please do join us for episode eight.

ELLIE: I can't wait.

JAMES: That's it from us.

BOTH: Bye!

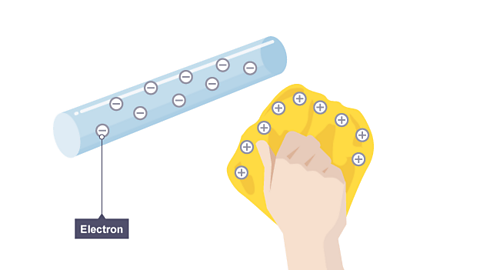

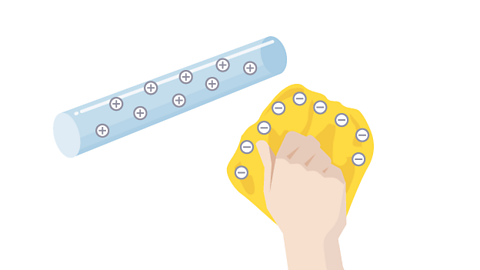

Charging by friction

When insulating materials rub against each other, they may become electrically charged. Electrons, which are negatively charged, may be ‘rubbed off’ one material and on to the other. The material that gains electrons becomes negatively charged. The material that loses electrons is left with a positive charge.

When a polythene rod is rubbed with a duster, the friction causes electrons to gain energy. Electrons gain enough energy to leave the atom and ‘rub off’ onto the polythene rod.

the polythene rod has gained electrons, giving it a negative charge

the duster has lost electrons, giving it a positive charge

1 of 3

If the rod is swapped for a different material such as acetate, electrons are rubbed off the acetateA type of transparent plastic film. and onto the duster.

- the acetate rod has lost electrons, giving it a positive charge

- the duster has gained electrons, giving it a negative charge

Both the rods and the duster are made of insulatorMaterial that does not allow charge or heat to pass through it easily. materials. Insulators prevent the electrons from moving and the charge remains static.

conductorAn electrical conductor is a material which allows an electrical current to pass through it easily. It has a low resistance., on the other hand, cannot hold the charge, as the electrons can move through them.

It is not possible for the positive charges to be transferred from one object to another. Therefore electrical charge can only be caused by the transfer of negative charges.

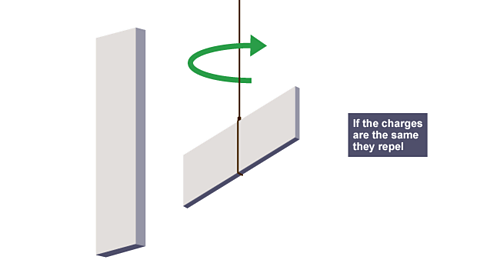

Electrical forces

A charged object will experience non-contact force from another charged object. The type of force will depend on the type of charge (positive or negative) on the two objects.

The properties of attractionObjects that tend to move together because of a force between them attract each other. and repulsionWhen two or more things are forced apart. are often used to show that an object is charged:

- a charged rod can pick up small pieces of paper

- a charged balloon can stick to the wall by attraction

- a charged rod can pull a stream of water towards it

Key fact: Opposite charges attract. Like (same) charges repel.

Example

If a negatively charged plastic rod is brought near to another negatively charged rod, they will move apart as they repel each other.

If a positively charged rod is brought close to a negatively charged rod, they will pull together as they attract each other.

1 of 3

The forces of attraction or repulsion are greater when the charged objects are closer.

Question

If a cloth rubs a plastic rod and the cloth is pulled away from the rod slightly, will the rod and cloth attract, repel or experience no force at all?

The rod and cloth will attract. This is true as long as there is enough friction to transfer electrons.

- If electrons are rubbed off the cloth and onto the rod - the cloth will be positively charged and the rod will be negatively charged.

- If electrons are rubbed off the rod and onto the cloth - the cloth will be negatively charged and the rod will be positively charged.

In both cases, the opposite charges will attract.

Electrical charge and current

There are two types of current: direct and alternating. In a direct currentDirect current is the movement of charge through a conductor in one direction only., the flow of electrons is consistently in one direction around the circuit. In an alternating currentAlso called ac. An electric current that regularly changes its direction and size., the direction of electron flow continually reverses.

Podcast: Electrical charge

In this episode, Ellie Hurer and James Stewart explore electrical charge and current. They also share the equation you need to calculate charge flow.

JAMES: Hello and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics Podcast.

ELLIE: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in physics and combined science.

JAMES: I'm James Stewart, I'm a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: And I'm Ellie Hurer, a bioscience PhD researcher.

This is episode one of our eight-part series all about electricity. And today we're going to be exploring electrical charge, current, and how to calculate them.

JAMES: Let's begin.

ELLIE: When we talk about how electricity flows, there are two key C's: charge and current.

JAMES: Yeah. Let's start with charge. There are two types of electric charge: positive and negative. Charged particles, such as electrons or ions, can transfer electrical energy. In metals, these charged particles are delocalised electrons that are free to move through the whole structure. Electrons are negatively charged.

ELLIE: And now let's move on to the second C, current. Electrical current is what we call the flow of electrically charged particles, such as electrons, as they move through an electrical conductor. It's how electrical energy flows through a circuit.

JAMES: Yeah, well, we measure current in amps using an ammeter. And when we do that, we measure the number of electrons passing a point in a circuit in just one second. The current is the same at any point in a circuit, so long as it's a single closed loop.

ELLIE: There are two types of electric current.

JAMES: Yeah, we have an alternating current and a direct current. That's AC and DC.

A direct current is when the electrons just flow in one direction around a circuit. So imagine a circuit that looks like a circle, for example. In a direct current, the electric current would either flow clockwise or anti clockwise. Not both.

ELLIE: An alternating current, on the other hand, is a current where the direction of the electron flow continually reverses.

JAMES: Yeah, the best way to remember the differences between the two is actually through their names. ‘Direct’ for doesn't change direction and ‘alternating’ for alternates direction.

ELLIE: So let's talk about how those work in a circuit. For an electrical charge to flow through a closed circuit, the circuit must include a source of potential difference.

Potential difference, also known as voltage, is the difference in energy the electrons have between two different points in a circuit. In a circuit, you've got to place a voltmeter in parallel with a component in order to measure the difference in energy from one side of the component to the other.

JAMES: Yeah, and by in parallel, what we mean is the voltmeter is on a separate branch of the circuit to the component in question.

ELLIE: We'll cover the difference between series and parallel circuits in more detail in episode 3.

JAMES: So for an electrical charge to flow through a circuit, there needs to be a voltage force. Let's use a lamp for an example. For that lamp to be turned on, you need to plug it into a wall socket, because the socket is the source of the voltage. Electricity can't flow through the plug up the wire and into the light bulb unless you plug it in.

ELLIE: Right, and when the lamp is plugged in, this then means the charge can flow, so you can then have a current. So, how do you measure the size of the electric current flowing through the wire to turn the light bulb on?

JAMES: There's luckily an equation for that Ellie, so grab your pen, grab your paper, we can write this one down together, if you want to do that.

The size of the electrical current is the amount of charge that passes a point per second, and the equation for calculating that is as follows: Charge equals current multiplied by time. I'll say that again. Charge equals current multiplied by time.

ELLIE: In this equation, we use the letter Q for charge, and it is measured in coulombs.

We then use the letter I for current, which is measured in amps, with the letter A. The unit for time is seconds, which is written as T. So this equation can also be expressed as Q equals I multiplied by T.

JAMES: Let's look at a practical example, and we'll give you the chance to, of course, work out the calculation, so grab your pen and paper.

So let's imagine you've made a simple circuit in your science class. It just has a battery, a light bulb, and a switch. Super simple. How would you calculate the charge that flows through the circuit if you knew the following? It had a current of 1.5 amps, and you want to measure the charge over the course of 60 seconds. I'll let you have a think for a moment and then we'll explain.

ELLIE: The equation is charge equals current multiplied by time. So you would take the current, 1.5 amps, then multiply it by the number of seconds, which is 60 seconds, to get the answer of 90 Coulombs. You can also rearrange that equation to find the current and in that case we would write the formula down as: current equals charge divided by time.

JAMES: Yeah, let's use that same circuit as an example. How would you work out the current, if the charge in the circuit was 90 coulombs over 60 seconds? I'll give you a few seconds to pause, then we can work it out together.

So to calculate the current flowing through the circuit, you would take the charge, 90 coulombs, and divide it by the number of seconds, that was 60, to get the answer, 1.5 amps. Simple as that.

Okay, let's summarise the key points we've learned from this episode. Really good one. Number one, for electrical charge to flow through a closed circuit, the circuit must include a source of potential difference. That's also known as voltage. Potential difference is the difference in energy the electrons have between two different points in a circuit.

Secondly, electrical current. We measure that in amps, and it's the amount of charge passing a point in the circuit per second. The equation that links these three is charge equals current multiplied by time. Well, you'll see that written down as Q equals I multiplied by T.

Third and finally, the current has the same value at any point in a single closed circuit. Thank you for listening to Bitesize Physics. If you found this helpful, please do go back, listen again and make some notes so you can come back any time you want and revise with us.

ELLIE: In the next episode of Bitesize Physics, we're going to focus on resistance and potential difference. So be sure to listen to the next episode and the rest of the series to make sure you're ready for your GCSE exam.

BOTH: Bye!

Extended syllabus content: Charge and electrical fields

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about charge and electrical fields. Click 'show more' for this content:

Electric charge

Electric charge is measured in coulombs (\(C\)). Electric charges create electrical fieldArea surrounding an electric charge that may influence other charged particles. around them. An electric field is any area where a electric forceA push or a pull. The unit of force is the newton (N). acts on an electric charge.

Did you know?

It would take approximately 6,000,000,000,000,000,000 electrons to have a charge of -1 coulomb.

The electric fields surrounding charged objects shows how they will interact with other charged particles.

Electric field shapes

Fields are usually shown as diagrams with arrows:

The direction of the arrow shows the way a positive charge will be pushed.

The closer together the arrows are, the stronger the field and the greater the force experienced by charges in that field. This means that the field is stronger closer to the object.

Key fact: Field lines point away from positive charges and towards negative charges.

Point charges

A point chargeThe electric charge at any single point (or position). Can be positive or negative. is the electric charge at any single point (or position). The electric field linesThe path taken by a positive charge when in an electric field. These are shown by imaginary lines. make a pattern that looks like the spokes of a wheel. They radiate inwards towards a negative charge, and outwards towards a positive one. These are both therefore called radial fieldWhen field lines spread out from a single point. E.g. an electron on its own will have a radial field..

Charge conducting spheres

The field pattern around a charge conducting sphereA spherical object that conducts a charge. Can be positive or negative. is similar to a point charge. A charge conducting sphere acts like a point charge when there are no other electric fields interacting with it.

Oppositely charged parallel plates

The field between two parallel plates, one positive and the other negative, is a uniform fieldWhen field lines are neat and ordered, usually from one charged plate to another..

The field lines are straight, parallel and point from positive to negative.

Did you know?

If the field is strong enough, charges can be forced though insulators such as air and a spark will occur. This is what happens during a lightning strike. It may also happen if a charged person touches a conductor. For example, a person dragging their feet across the carpet may become charged, so if they reach out to touch a door handle there is a spark and they feel a small shock.

A Van de Graaff generatorA machine that causes friction between a rubber belt and plastic rollers in order to build up electrical charge on a metal dome. A large potential difference is generated. removes electrons to produce a positive charge. A person does not have to touch the Van de Graaff generator to start feeling the effects, as static electricity is a non-contact force. This force will act on any charged particle in the electric field around the generator.

Current

Electrical current is the rate of flow of electric charge. When current flows, electrical workWork is the measure of energy transfer when a force (F) moves an object through a distance (d). is done and energy transferred. The amount of charge passing a point in the circuit can be calculated using the equation:

charge = current × time

\(Q = I \times t\)

This is when:

- charge (Q) is measured in coulombs \(\mathrm{C}\)

- current (I) is measured in amps (A)

- time (t) is measured in seconds (s)

One amp is the current that flows when one coulomb of charge passes a point in a circuit in one second.

Example

A current of 1.5 amps (A) flows through a simple electrical circuit.

How many coulombs of charge flow a point in 60 seconds?

\(Q = I \times t\)

\(Q = 1.5 \times 60\)

\(Q = 90~C\)

Question

How much charge has moved if a current of 13 A flows for 10 s?

\(Q = I \times t\)

\(Q = 13 \times 10\)

\(Q = 130~C\)

Measuring current

Current is measured using an ammeterA device used to measure electric current.. To measure the current through a component, the ammeter must be placed in seriesA way of connecting components in a circuit. A series circuit has all the components in one loop connected by wires, so there is only one route for current to flow. with that component.

Ammeters may be digital or analogue and can have the ability to measure different ranges of current. For example, a microammeter may be used to detect very small changes in current whereas a digital ammeter in school usually gives the current to the nearest 10th of an amp.

Alternating and direct current

An electric current flows either as a direct current or as an alternating current.

Direct current

A direct current flows in only one direction.

On a voltage-time graph this would appear as a straight horizontal line at a constant voltage.

Car batteries, dry cells and solar cells all provide a direct current (dc) that only flows in one direction.

Alternating current

An alternating current regularly changes direction.

On a voltage-time graph, this would appear as a curve alternating between positive and negative voltages. The positive and negative values indicate the direction of current flow.

Free electrons

The particles in a metal are held together by strong metallic bonds.

The particles are close together and in a regular arrangement.

Metals atoms have loose electrons in the outer shells, which form a 'sea' of delocalised or free negative charge around the close-packed positive ions.

These loose electrons are called free electrons.

They can move freely throughout the metallic structure.

An electric current is the flow of these free electrons in one direction.

Direction of flow of free electrons

Energy is required to make the free electrons travel in one direction.

An electric cell (often called a battery) can supply this energy and make free electrons move in a metal conductor connected between its two terminals.

Electrons flow from the negative terminal through the conductor to the positive terminal.

They are repelled by the negative terminal and attracted by the positive terminal.

Electromotive force

The electromotive force (EMF) is the amount of work done by a cell in moving a unit of charge around a complete circuit. It is essentially the maximum voltage a cell is capable of supplying to a circuit. Just like voltage, EMF is measured using the unit Volts (V)

Extended syllabus content: EMF equation

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know the EMF equation. Click 'show more' for this content:

To calculate the EMF of a power source, the below equation could be used:

\(E = \frac{W}{Q}\)

Where:

\(E = EMF (V)\)

\(W = Work done (J)\)

\(Q\) = \(Charge\) (\(C\))

Extended syllabus content: Conventional current

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about conventional current. Click 'show more' for this content:

The direction of conventional current

Electric current was discovered before physicists knew about free electrons.

It was originally thought that the current was flowing in the opposite direction, ie from the positive terminal of the battery, through the conductor, to the negative terminal.

For a number of reasons, although this is now known to be the wrong direction, it is still the direction of current marked on all circuit diagrams.

It is called the direction of conventional current.

Key points

The direction of conventional current is from the positive terminal, through the conductor, to the negative terminal.

The direction of free electron flow is from the negative terminal, through the conductor, to the positive terminal.

The direction of conventional current is the direction marked on all circuit diagrams.

The symbol for electric current is I.

Potential difference and resistance

Video: Potential difference experiment

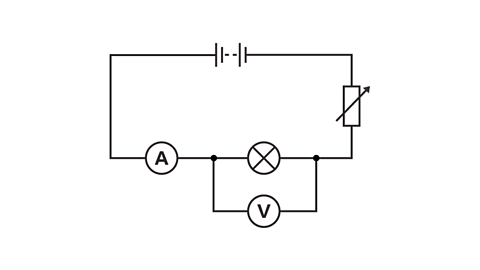

A demonstration of the key points of the required practical to investigate the I-V characteristics of circuit elements.

This investigation shows how a current, when passed through a component, changes as the potential difference changes.

The resulting graph is called the I-V characteristic.

An ohmic conductor is a resistor at constant temperature. You can measure the I-V characteristic of an ohmic conductor by setting up a circuit like this one.

Use the power pack to change the potential difference and then measure the potential difference across the resistor and the current through the circuit. Ohm's Law states that, for an ohmic conductor, the potential difference across a component is proportional to the current through it.

Voltage equals current multiplied by resistance. Therefore, the graph for an ohmic conductor shows that resistance stays the same as current changes.

Other components do not behave in the same way. You can explore this by using the same circuit, but changing the component across which the voltage is measured. So instead of using an ohmic conductor you could use a filament lamp.

With a filament lamp you will see that resistance increases as the current increases. This is because the temperature of the filament increases. Therefore, less current flows per potential difference unit and the graph gets shallower. This sketch graph shows how this looks.

Or if you use a diode the current only flows in one direction. In the other direction, the resistance is very high.

The sketch graph for this investigation looks like this.

Repeat each reading three times to allow you to identify and discount anomalies, before calculating an average potential difference for each current. Use a milliammeter rather than standard ammeter to increase resolution. A milliammeter measures in milliamperes rather than amperes.

The current through a component depends on both the resistance of the electrical componentsA device in an electric circuit, such as a battery, switch or lamp. and the potential difference across the component.

Measuring potential difference

To measure the potential difference across a component, a voltmeter must be placed parallel circuitA way of connecting components in a circuit. A parallel circuit has components on separate branches, so the current can take different routes around the circuit. with that component in order to measure the difference in energy from one side of the component to the other. Potential difference is also known as voltage and is measured in volts (V).

Key fact: Potential difference (or voltage) is a measure of energy, per unit of charge, transferred between two points in a circuit. A potential difference of 1 volt means that 1 joule of work is done per coulomb of charge.

Podcast: Current, resistance and potential difference

In this episode, Ellie and James explore current, resistance and potential difference. They also discuss the relationship between current and resistance in different components.

ELLIE: Hello, and welcome to the BBC Bitesize Physics podcast.

JAMES: The series designed to help you tackle your GCSE in physics and combined science. I’m James Stewart, I’m a climate science expert and TV presenter.

ELLIE: And I’m Ellie Hurer, a bioscience PhD researcher.

ELLIE: Just a reminder that we're covering lots of topics in this series, so make sure you take a look at the rest of the episodes too.

JAMES: Yeah, let's get started because today we're talking all about current, resistance and potential difference.

In the last episode of the podcast, we gave you definitions of current and charge. Feel free to go back and listen to that one, but in this episode today we're gonna be talking about how those actually work when the current flows through an electrical component, something like a wire.

ELLIE: The current through component depends on both the resistance and the potential difference, also known as the voltage across the component.

JAMES: Resistance in a circuit is provided by components. You can have a component that is called a resistor. But other components such as a bulb, motor, and even wires provide resistance.

ELLIE: Resistance reduces the current as it makes it harder for the current to flow. And there's an equation that links the amount of resistance with current and potential difference.

So grab your pen and paper. The equation is: potential difference equals current multiplied by resistance. Let me repeat that again. Potential difference equals current multiplied by resistance.

JAMES: Now remember that potential difference is also known simply as voltage and is measured in volts. Current is measured in amps, and resistance is measured in ohms. The equation on an exam paper could therefore be written as: V equals I multiplied by R.

ELLIE: I know that's a lot to take in, so maybe pause this episode for a moment and write down that equation and then let's apply it to an example.

JAMES: Imagine a circuit. It's a simple one with a lightbulb, a cell, and an ammeter. How would you calculate the potential difference if the current is 2 amps and the lightbulb has a resistance of 58 ohms?

ELLIE: Well, potential difference equals current multiplied by resistance, so 2 amps multiplied by 58 ohms. And your answer would be… 116 volts.

JAMES: If you want to try more examples just like this to prepare you for the kind of questions you might get in an exam, visit the BBC Bitesize website for quizzes and more.

ELLIE: In an electric circuit, a resistor is a component that resists current. All components in a circuit have some resistance, but there are a few specific resistors you should learn about.

JAMES: Yeah, let's look at the first type of resistor, the fixed resistor, which always has the same value for resistance. This means that if you increase the potential difference, the current must also increase, because potential difference equals current multiplied by resistance.

ELLIE: In fact, potential difference and current are directly proportional. So what that means is that if the potential difference doubles, so does the current.

JAMES: And that type of resistor is called an ohmic conductor. There are other types of resistors that aren't ohmic, which means their value for resistance changes. And I think we should get stuck into that as well. When it comes to components like lamps and thermistors, the resistance is not a constant. It actually changes as the current does.

ELLIE: And for example, let's take, say, a filament light bulb. That's the kind of light bulb that has a squiggly wire in it. In a filament lightbulb, the resistance increases as the temperature of the lightbulb increases. So once it's at its full brightness, it gets pretty hot. So the resistance will have increased.

JAMES: And that's because the particles in that filament of the lightbulb are vibrating faster because of that higher temperature, making it harder and harder for the electrons to flow through. Now, this is not a proportional relationship, as if the potential difference increases, the current does not increase at the same rate.

Let's look at another example, a diode. So in this example, the current that flows through a diode only flows in the one direction. So diodes have a very high resistance in the reverse direction.

ELLIE: In the forward direction. Diodes have a large resistance at low potential differences, but at higher potential differences, the resistance decreases a lot. So, current increases.

JAMES: Okay, let's talk about resistance in another type of component, a thermistor.

ELLIE: When the temperature of a thermistor increases, it gets hotter and the resistance decreases.

And when the temperature decreases and gets cooler, the resistance increases.

Yeah, there's one type of thermistor that you can find in many homes. A thermostat is the device people use to change the temperature of the heating around the house.

JAMES: And finally let's talk about resistance in another type of component yes, we haven't run out of components just yet, an LDR. An LDR is a light dependent resistor and it has a similar pattern to a thermostat.

Now they're the things you have on like your light sensors at home, so we use them for street lights, night lights, that kind of thing.

The resistance of an LDR decreases as light intensity increases. And the resistance increases as the light intensity decreases.

ELLIE: So, how might questions about all these different components and resistance come up in an exam?

JAMES: Great question! Uh, yeah, you might be shown or even asked to draw the correlation on a graph. So, grab your pen and your paper and we'll show you just how to do that.

ELLIE: So, start off by drawing a big cross graph with two intersecting lines. Label the y axis, the vertical one, as current. And label the x axis, the horizontal one, as potential difference.

JAMES: With an ohmic conductor, resistance is a diagonal line from one corner of the graph to the other, passing through the origin, that's the intersection of the axis.

ELLIE: And when it comes to a diode, resistance increases with a diagonal line upwards once the potential difference has reached a small positive value.

JAMES: And finally when it comes to a filament lamp, resistance curves in an s shape across both the bottom left and the top right square of the graph.

ELLIE: While drawing this out might help you start to visualise it, I definitely recommend checking out the Bitesize website to see what these graphs actually look like.

Okay, so let's recap the main lessons we learned in this episode. So firstly, we learned the equation potential difference is equal to current multiplied by resistance.

Next, we learned that the current through an ohmic conductor is directly proportional to the potential difference across the resistor.

And last but not least, the resistance of components such as lamps, diodes, thermistors and LDRs is not constant.

JAMES: Thank you for listening to Bitesize Physics. In the next episode we are going to dig in to series and parallel circuits.

ELLIE: If found this helpful, go back and listen again and make some notes so you can come back to this as you revise.

BOTH: Bye!

Extended syllabus content: Energy, voltage and charge

If you are studying the Extended syllabus, you will also need to know about energy, voltage and charge. Click 'show more' for this content:

When a charge moves through a potential difference, electrical work is done and energy transferred. The potential difference can be calculated using the equation:

\(potential~difference = \frac{work done}{charge}\)

\(V = \frac{W}{Q}\)

This is when:

- potential difference (V) is measured in volts (V)

- work done(W) is measured in joules (J)

- charge (Q) is measured in coulombs ©

One volt is the potential difference when one coulomb of charge transfers one joule of energy.

Example

What is the potential difference between two points if 2 C of charge shifts 4 J?

\(V = \frac{W}{Q}\)

\(V = \frac{4}{2}\)

\(V = 2~V\)

Resistance

When a charge moves through a potential difference, electrical work is done and energy transferred. The potential difference can be calculated using the equation:

potential difference = current × resistance

\(V = I \times R\)

This is when:

potential difference (V) is measured in volts (V)

current (I) is measured in amps (A)

resistance (R) is measured in ohms (Ω)

One volt is the potential difference when one coulomb of charge transfers one joule of energy.

Key fact: Conductors have a low resistance. Insulators have a high resistance.

Example

What is the potential difference if a current of 2 A flows through a resistance of 40 Ω?

\(V = I \times R\)

\(V = 2 \times 40\)

\(V = 80~V\)

Question

What is the resistance of a component if 12 V causes a current of 2 A through it?

\(V = I \times R\)

\(R = \frac{V}{I}\)

\(R = \frac{12}{2}\)

\(R = 6~Ω\)

Investigating the factors that affect resistance

Jonny Nelson explains resistance with a GCSE Physics practical experiment.

Experiment - wire length

There are different ways to investigate the factors that affect resistance. In this practical activity, it is important to:

- record the length of the wire accurately

- measure and observe the potential difference and current

- use appropriate apparatus and methods to measure current and potential difference to work out the resistance

Aim of the experiment

To investigate how changing the length of the wire affects its resistance.

Method

- Connect the circuit as shown in the diagram above.

- Connect the crocodile clips to the resistance wire, 100 cm apart.

- Record the reading on the ammeter and on the voltmeter.

- Move one of the crocodile clips closer until they are 90 cm apart.

- Record the new readings on the ammeter and the voltmeter.

- Repeat the previous steps reducing the length of the wire by 10 cm each time down to a minimum length of 10 cm.

- Use the results to calculate the resistance of each length of wire by using \(R = \frac{V}{I}\), where R is resistance, V is voltage and I is current.

- Plot a graph of resistance against length for the resistance wire.

- Results

Click 'Show answer' to see the example results and analysis.

Results

| Length (cm) | Potential difference (V) | Current (A) | Resistance (Ω) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 1.20 | 0.16 | 7.5 |

| 90 | 1.18 | 0.17 | 6.8 |

| 80 | 1.00 | 0.17 | 5.9 |

| 70 | 0.96 | 0.18 | 5.3 |

| 60 | 0.93 | 0.21 | 4.4 |

| 50 | 0.89 | 0.25 | 3.6 |

| 40 | 0.84 | 0.27 | 3.1 |

| 30 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 2.4 |

| 20 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 1.4 |

| 10 | 0.41 | 0.63 | 0.7 |

Analysis

Evaluation

From the graph it can be seen that the longer the piece of wire, the higher the resistance. Resistance is directly proportional to length as the graph gives a straight line through the origin.

Quiz

Teaching resources

Are you a physics teacher looking for more resources? Share these short videos with your students:

More on Electricity and magnetism

Find out more by working through a topic

- count3 of 7

- count4 of 7

- count5 of 7

- count6 of 7