Life processes

The proper name for a living thing is a living organism. A living organism can be, amongst other things, a plant or an animal. But how can we tell the difference between something that is living, or dead, or has never been living?

To be classified as living there are seven things an organism must show:

The phrase MRS GREN is one way to remember them:

| MRS GREN | Definition |

|---|---|

| Movement | all living things move, even plants |

| Respiration | getting energy from food |

| Sensitivity | detecting changes in the surroundings |

| Growth | all living things grow |

| Reproduction | making more living things of the same type |

| Excretion | getting rid of waste |

| Nutrition | taking in and using food |

MRS GREN

Sometimes it’s easy to tell if something is living or not. A teddy bear might look like a bear, but it cannot do any of the seven things it needs to be able to do to count as being alive.

A car can move, it gets energy from petrol (like nutrition and respiration), it might have a car alarm (sensitivity), and it gets rid of waste gases through its exhaust pipe (excretion). But it cannot grow or make baby cars. So, a car is not alive.

Cells

All living organisms are made up of cells. Cells are the building units of life - the basic building blocks of all animals and plants. They are so small, you need to use a light microscope to see them.

The light microscope

You can focus the image using one or more focusing knobs. It is safest to focus by using the knobs to move the stage downwards, rather than upwards. There is a chance of the objective lens and slide colliding if you focus upwards.

Microscopes often have three or four objective lenses on a turret that you can turn. It is wise to observe an object using the lowest magnification lens first. You may need to adjust the focus and the amount of light as you move to higher magnifications.

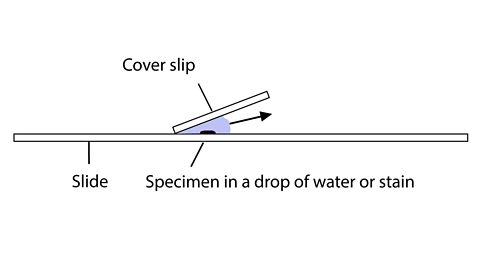

Making a slide

Onion cells are easy to see using a light microscope. Here is a typical method for preparing a slide of onion cells:

- cut open an onion

- use forceps to peel a thin layer from the inside

- spread out the layer on a microscope slide

- add a drop of iodine solution to the layer

- carefully place a cover slip over the layer

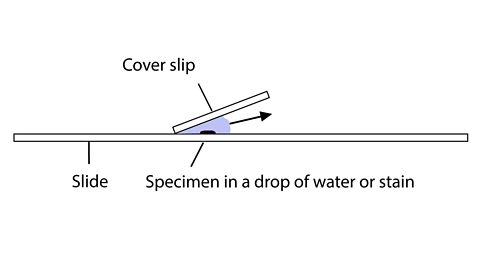

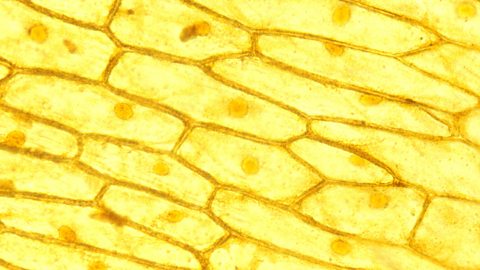

Observing cells

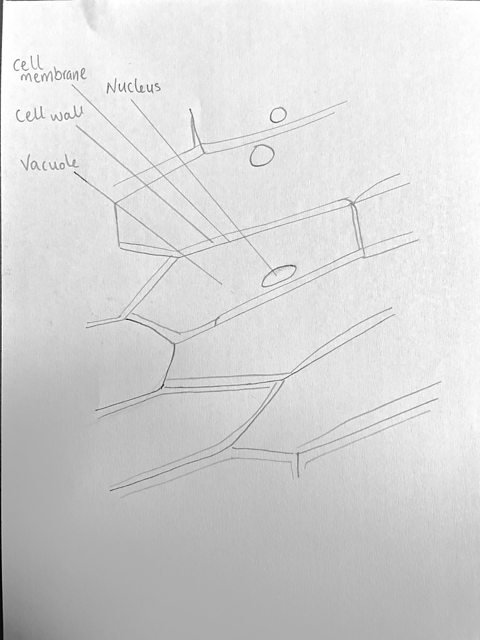

When you observe cells, it is usual to make a drawing of what you see. Very often there is so much to see that you can only aim to draw part of it:

- use pencil rather than pen or colours

- outline the features as accurately as you can using black lines.

- no shading

- label your drawing with the name of the sample and the total magnification you used

Let’s take a look at how to observe cells under a microscope.

No prizes for guessing the first thing you’ll need — a microscope.

But don’t worry if you don’t have one of your own, ask your school if they have one you can use.

Then you’ll need an onion, that’s where you’ll get your plant cells. Some food colouring, blue or green works best, a cotton bud and a mouth. Probably best to use your own!

Let’s begin by looking at some plant cells.

Cut a small chunk from your onion — be careful with knives, ask an adult if you need help.

Peel a thin layer of that chunk and put it on your slide. This is what’s called the epidermis.

Using a drop of food colouring, stain the layer so you can see the cells.

Pop a cover slip on the slide and then put the slide onto the microscope.

Take a look.

Check out that strong cell wall structure! It is solid so that it keeps the plant’s shape and structure.

But this experiment isn’t over. You can look at some animal cells too.

Grab a fresh slide and pop a drop of your food colouring on there.

Take your cotton bud and rub the inside of your cheek — told you you’d need a mouth!

Transfer the cheek cells to the slide by rubbing the swab all over it.

Drop the cover slip on the slide and stick it on the microscope.

Go find those animal cells.

Unlike the plant cells, animal cells are soft and fleshy. Animals don’t need cells to keep their structure — that’s what skeletons are for.

And there you have it!

Total magnification

The magnification of each lens is shown next to the lens:

Total magnification = eyepiece lens magnification × objective lens magnification

For example, if the eyepiece magnification is ×10 and the objective lens magnification is ×40:

Total magnification = 10 x 40 = ×400 (400 times)

The microscope is thought to have been invented by a Dutch father-son team of spectacle makers named Hans and Zacharias Janssen in the 1590s. However, it wasn’t until the mid-seventeenth century that it was first used to make discoveries.

In 1665 a scientist called Robert Hooke was using a microscope to look at a thin slice of cork. He saw lots of little boxes in the cork, and he called these boxes ‘cells’.

Animal cells and plant cells

Animal cells usually have an irregular shape, and plant cells usually have a regular shape. Cells are made up of different parts.

It is easier to describe these parts by using diagrams:

Animal cells and plant cells both contain:

- cell membrane

- cytoplasm

- nucleus

- mitochondria

Plant cells also contain these parts, which are not found in animal cells:

- cell wall

- vacuole

- chloroplasts

The table summarises the functions of these parts:

| Part | Function | Found In |

|---|---|---|

| Cell membrane | Controls the movement of substances into and out of the cell | Plant and animal cells |

| Cytoplasm | Jelly-like substance, where chemical reactions take place | Plant and animal cells |

| Nucleus | Carries genetic information and controls the activities of the cell | Plant and animal cells |

| Mitochondria | Where most respiration reactions happen | Plant and animal cells |

| Vacuole | Contains a liquid called cell sap, which keeps the cell firm | Plant cells only |

| Cell wall | Made of a tough substance called cellulose, which supports and strengthens the cell | Plant cells only |

| Chloroplasts | Absorbs light energy and converts it into chemical energy (food) | Green plant cells only |

Find out from a greengrocer and a butcher how the structure of a particular cell affects their produce

TILLY: My name's Tilly, I'm a butcher. I cut and sell meat over the counter to the public.

Biology was probably my favourite subject, funnily enough.

I've always been fascinated with bodies, with animals, with humans, how they work, what they're made up of.

Meat is composed of animal cells: the cell membrane, the cytoplasm, and the nucleus. Meat feels squishy, very malleable.

ADAM: My name is Adam, and I work for a fruit and vegetable business.

Plant cells have a rigid cell structure. They are made up of a cell wall, cell membrane, cytoplasm, vacuole, nucleus, and chloroplasts.

Plants feel firm because of their cellular walls. This is why fruit and vegetables have a nice crunch and firmness to them.

TILLY: Once you take the bones out of the meat itself, it's very easy to tie it up and change the shape of it.

ADAM: Some fruit and vegetables have really strong cells, such as root vegetables: carrots, fruits like apples. When they're well watered, the vacuoles are firm. But when the plant starts to lose water, we start to see the plants going wilted and droopy. We use temperature and humidity to keep the fruit and vegetables fresh.

Tilly: The best thing about being a butcher, I would say for me, is talking about how to cook meat, how it's raised, and seeing people choose to buy ethical and sustainable meat.

Adam: Best thing about my job is definitely eating the fruit and vegetables every day.

Activity - Cells

Cells and their functions

How to make a model plant cell

This is how you make a model plant cell.

There are a few things you'll need:

A plastic box, a small sealable sandwich bag filled with water, cling film, some peas -frozen or otherwise, some water with green food colouring - if you've got any, and a trusty grape.

Line the plastic box with cling film.

Pop the sealed plastic bag in.

Spread the peas generously.

Get the grape in there.

And finally, top it up with the coloured water.

Then you'll have a model plant cell with all of its parts:

Cell wall, which keeps everything together, Cell membrane, which surrounds the cytoplasm. Vacuole, the space within the cytoplasm that contains fluids and nutrients. Nucleus, which contains the cell's genetic material. Cytoplasm, where the cell's chemical reactions happen. Chloroplasts, where photosynthesis takes place.

So there you have it — the building blocks of plant life!

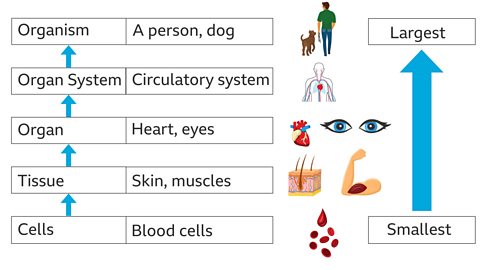

Humans are multicellular. That means we are made of lots of cells, not just one cell.

- Cells are the basic building blocks of all animals and plants

- The same type of cells group together to form a tissue

- When different tissues group together they form an organ

- Organs working together to form organ systems

- Different organ systems work together to form an organism

How multicellular organisms are organised.

Multicellular organisms are organised into increasingly complex parts.

Cells are the building blocks of life.

Tissue is made when specialised cells with the same function group together. For example, millions of muscle cells make up muscle tissue.

An organ is made from two or more tissues, which all work together to do a particular job, like the heart in animals or a leaf in a plant.

An organ system is made of a group of organs which all work together to do a particular job, such as the nose, trachea, bronchi and lungs, which all make up the gas exchange system.

PRESENTER 1: Yeah, so one of the systems in the human body is the digestive system. Ours is simpler than some other animals, like cows and deer have multiple stomachs, we just have the one.

PRESENTER 2: So as you can see, there are lots of tissues and organs that make up our digestive system. But what's the difference between them?

PRESENTER 1: So, yeah, these are some key things on your school syllabus. Firstly, you need to know that a tissue is a group of cells in the same place all doing the same thing. There are loads of cells in your mouth making saliva. Imagine if the saliva-making tissue all disappeared. You'd have the driest mouth in the world.

PRESENTER 2: I sometimes get that when I'm nervous on television. But anyway, how about an organ, then?

PRESENTER 1: So organs are these things here, like the stomach and liver. They do an overall job. There's an amazing organ called a spleen that can help you hold your breath underwater for longer if you have a really big one. Penguins have massive spleens. Anyway, you need to know that an organ is a group of different tissues working together to achieve an overall goal.

PRESENTER 2: OK, gotcha. So we know what a tissue and an organ is. What about a system?

PRESENTER 1: A system is a group of organs that work together to do an overall task. So our nervous system is our brain and all our nerves, and that allows us to think, feel, move, dance and so on. Our digestive system allows us to eat delicious food, digest it; which means break it down and absorb it.

Speaking of which, there's a guy in France who once ate an entire plane by breaking it into tiny pieces, but I would not advise that at all.

PRESENTER 2: Is that true? That's astonishing! OK, I definitely wouldn't do that. All right, so a bit of a recap for us on this.

PRESENTER 1: To recap, cells make tissues, tissues make organs, and organs make systems. Some living things are made from a single cell. We call them unicellular — like a unicycle but with a cell. And they don't have to worry about any of this because they're just a cell. We're multicellular, which means loads of cells all together miraculously forming working human beings like ourselves.

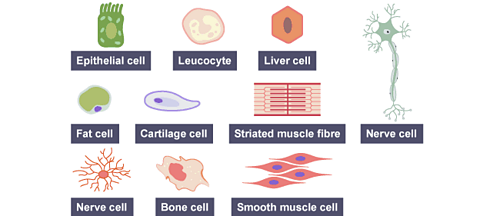

The cells in many multicellular animals and plants are specialised, so that they can share out the processes of life. They work together like a team to support the different processes in an organism.

Animal cells and plant cells can form tissues, such as muscle tissue in animals. A living tissue is made from a group of cells with a similar structure and function, which all work together to do a particular job.

When different tissues group together they form an organ.

An organ system is made from a group of different organs, which all work together to do a particular job.

An organism is formed when different organ systems work together.

- you are an organism

- the circulatory system is an organ system

- your heart is an organ

- it has muscle tissue,

- muscle tissues are made from muscle cells

Specialised cells

Find out how a sports therapist uses his knowledge of specialised cells to help his clients

It’s really important to know about different types of muscle cells because this allows us to understand how to best use them.

I'm Ruben Tabares, Strength and Conditioning Coach, Nutritionist, and Sports Therapist.

My job is to make people stronger, faster, to make them healthier.

Specialised cells are designed to carry out a particular role in the body, such as red blood cells, which are designed to carry oxygen.

Nerve cells help with the contraction or relaxation of muscles, depending on the specific job you need them to do.

The type of muscle that helps with digestion is called smooth muscle.

Cardiac muscle pumps blood around the body.

Skeletal muscle is made out of specialised skeletal muscle cells.

It’s not all about having big muscles. I personally like everyone I work with to have muscle fit for purpose.

There’s absolutely no difference between an elite-level sportsperson, such as Usain Bolt and a person who’s never really trained before. If they’re both running, they’re using the same muscles. The only difference is someone like Usain Bolt has trained his muscles over a longer period of time and when he pushes, he has more power in his muscles.

It’s really important to keep our muscles healthy because we want to be able to do the same things when we’re young as when we’re old. By having strong muscles, you ensure that as you get older, you can still run, walk up and down the stairs, and do all the other things you did when you were younger.

The best thing about my job is watching people achieve their goals. I do that with many different athletes across many different sports and that is for sure the best thing about my job.

This diagram shows examples of some specialised animal cells. Notice that they look very different from one another.

These tables show examples of some specialised animal and plant cells, with their functions and special features:

Activity - Specialised cells

Unicellular organisms

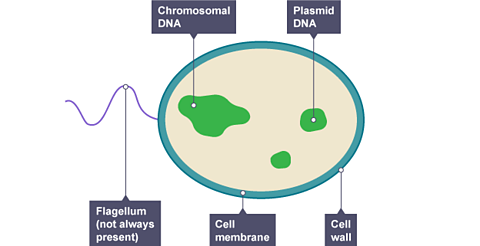

A single celled, unicellular organism is a living thing that is just one cell. There are different types of unicellular organism, including:

- bacteria

- protozoa

- unicellular fungi

- algae

- Archaea

You might be tempted to think that these organisms are very simple, but in fact they can be very complex. They can carry out all seven life processes - movement, respiration, sensitivity, growth, reproduction, excretion and nutrition.

They have adaptations that make them very well suited for life in their environment.

Bacteria

Bacteria are tiny. A typical bacterial cell is just a few thousandths of a millimetre across.

The structure of a bacterial cell is different to an animal or plant cell.

Protozoa

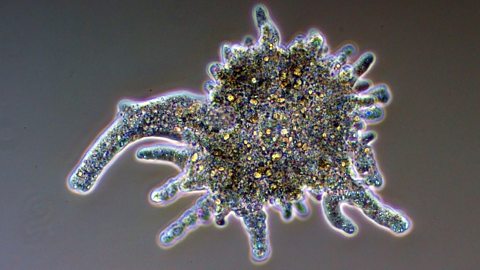

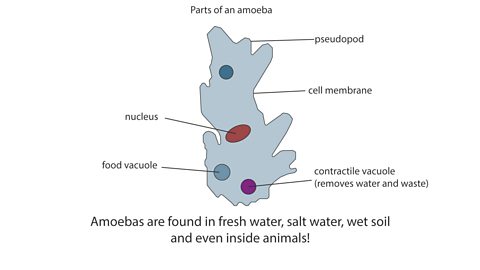

Protozoa are single celled organisms that live in water or in damp places. The amoeba is an example of one.

Although it is just one cell, it has adaptations that let it behave a bit like an animal:

- it produces pseudopodia (“false feet”) that let it move about

- its pseudopodia can surround food and take it inside the cell

- contractile vacuoles appear inside the cell, then merge with the surface to remove waste

Yeast

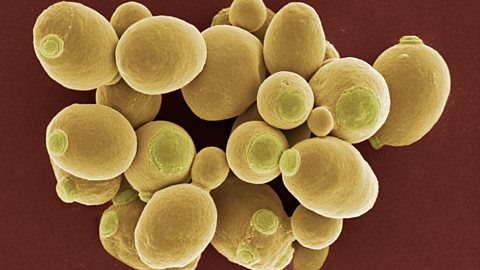

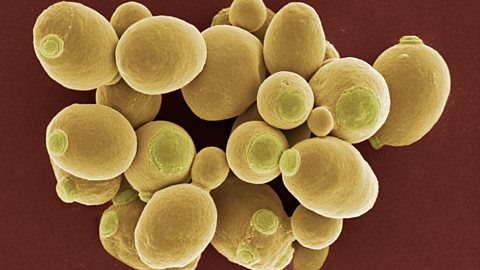

You may be familiar with fungi from seeing mushrooms and toadstools. Yeast are single celled fungi. They are used by brewers and wine-makers because they convert sugar into alcohol, and by bakers because they can produce carbon dioxide to make bread rise.

Yeast cells have a cell wall, like plant cells, but no chloroplasts.

Yeast can reproduce by producing a bud. The bud grows until it is large enough to split from the parent cell as a new yeast cell.

More on Biology

Find out more by working through a topic

- count5 of 14

- count6 of 14

- count7 of 14

- count8 of 14