Could this year's hurricane season 'go Greek'?

- Published

The number of named tropical cyclones in the Atlantic this year is forecast to be double the average of a typical season and exceed the number of pre-determined names.

If this happens, the letters of the Greek alphabet will be used to name further storms - which would be only the second time this has occurred.

The Atlantic hurricane season is now heading into its most active phase with the peak of the season running from now until late October.

By this stage of the year, statistics from the United States' National Hurricane Center show that we would normally have had three named storms and one hurricane. This year, however, has been far from normal.

Up to mid-August there have been nine named storms and two hurricanes. The year got off to a very busy start with Arthur and Bertha forming before the official start to the season in June, and more recently hurricanes Hanna and Isaias became the earliest eighth and ninth named systems on record.

This, though, hasn't surprised meteorologists as conditions were forecast to come together for a busy season.

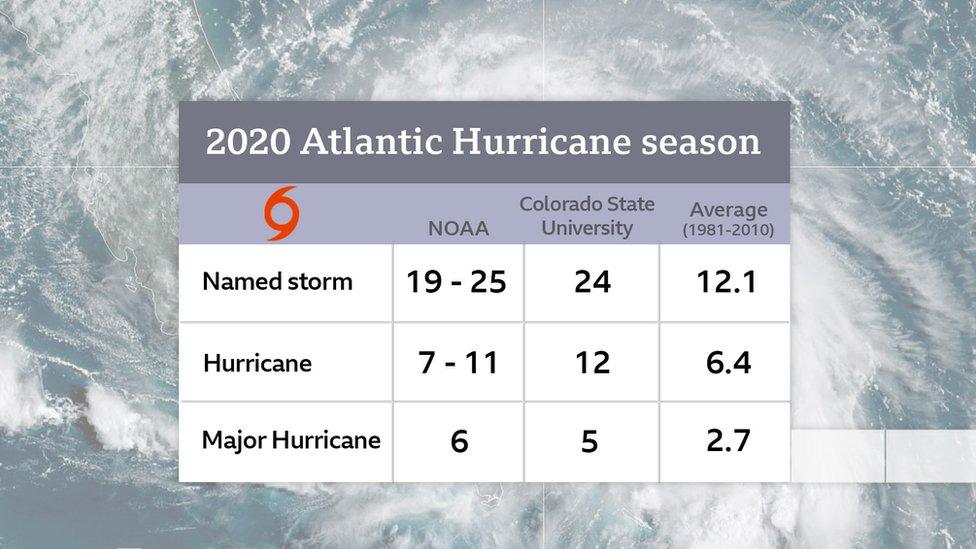

Seasonal forecasts from the National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Colorado State University in the US both predicted 2020 would see around double the 1981-2010 average number of named storms. There are only 21 names on each year's dedicated World Meteorological Organization list so, if the forecasts come to fruition, the Greek alphabet will be used to name the rest.

Gerry Bell, NOAA's lead hurricane season forecaster stated that his organisation's forecast of as many as 25 named storms was a first for them.

The Greek alphabet has only been used once before, in the record-breaking 2005 hurricane season when there were 27 named storms. It ended with Tropical Storm Zeta at the end of December.

It was also the season when Hurricane Katrina, a Category 5 hurricane, caused extensive damage in Louisiana and Mississippi - one of the costliest natural disasters in US history.

Why has this season been so busy?

Like baking a cake, there are a number of ingredients we need to produce a hurricane or tropical storm. These include a sea surface temperature greater than 26C and instability in the atmosphere around western Africa. There also needs to be little wind shear - changes in wind speed and direction throughout the atmosphere that can affect the development of storms.

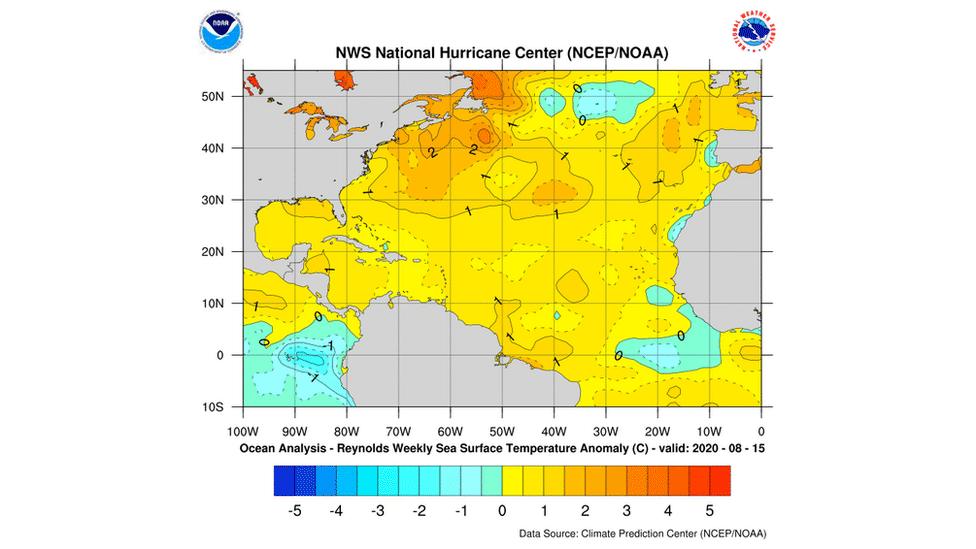

And that's what we have seen so far this year. Sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic have consistently been around 1-2C above normal over the summer, with meteorologists at Colorado State University suggesting sea surface temperature anomalies are ranked as the fourth warmest on record. As we approach the end of August and head into September, the sea surface temperature will remain high enough to supercharge tropical storm formation.

The other main ingredient for a tropical storm - wind shear - has also been extremely low throughout July. The seasonal forecasts issued suggest there is a strong connection between July wind shear and August-October averaged wind shear, so we can therefore also expect this to enhance storm activity in the Atlantic.

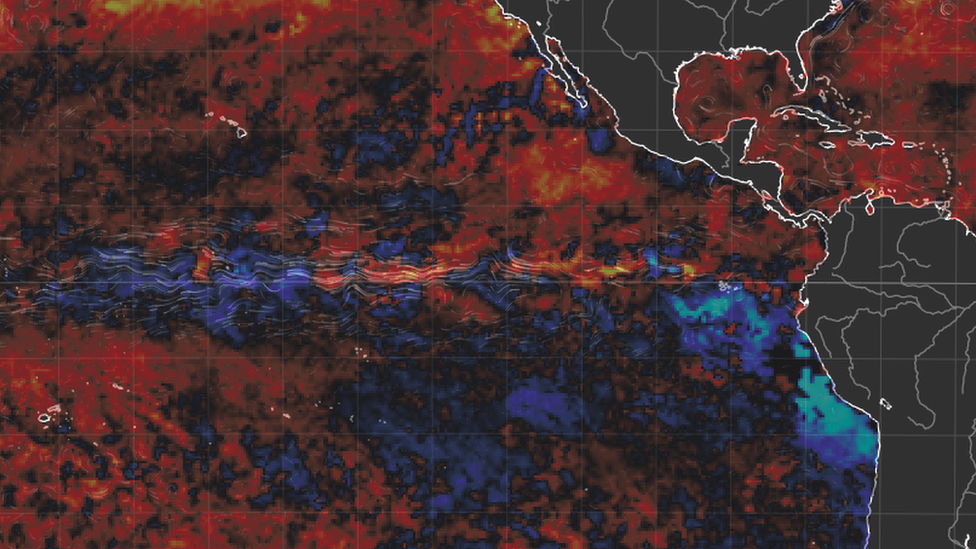

The final factor contributing to the forecast of an active season is a natural climatic pattern called ENSO - El Nino Southern Oscillation. This describes the state of sea surface temperatures and wind patterns across the Pacific Ocean, which have climatic implications across the globe.

When this oscillation is in a neutral or negative phase - known as La Nina - hurricane activity tends to be increased.

The blue indicates below average sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean

With sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific being around -0.4 C below average, Australia's Bureau of Meteorology are forecasting a 70% chance of it developing this year.

Is climate change a contributing factor?

Linking tropical cyclones to climate change is complicated. Climatologists are actively researching this area and studies so far suggest that we could see more intense major storms in a warming world.

However, as there are so many factors involved we cannot say whether man-made climate change has an effect on individual seasons such as this.