When it comes to feeding our children, especially as they grow into toddlers and pre-schoolers, it can often feel like there’s no rhyme or reason to what they will eat.

Sure, they might have a favourite food – but they can’t have beans on toast every day, right? If they’re particularly fussy, you might be starting to consider whether your child has a sensory issue.

Paediatric dietitian Lucy Neary explains that, first of all, you should think about your child's senses and sensory preferences that we all have, no matter our age.

“For example, you might have your shower boiling hot, I might have mine cold. Some of us have our music really loud, others don't,” Lucy says.

And eating is affected most of all as it “is one of the only things we do in life that uses all eight of our senses at once.”

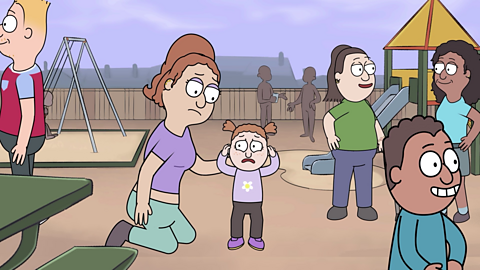

Toddlers and pre-schoolers won’t understand their preferences yet and will be unable to express them – which often results in tantrums or sensory meltdowns - so it’s important for parents to recognise the role senses play and the impact that preferences have on mealtimes.

What senses affect children eating?

Lucy explains that there are the five senses we were taught as kids, but there are more that you might not be so familiar with. Here are some that can affect how you experience food and the action of eating…

Taste

Sound

Sight

Touch

Smell

Interoception – how we feel inside our body, including hunger, thirst and fullness

Vestibular sense – our sense of balance and the position of our body

Proprioception – our sense of movement and where our body is within a space

Everyone has preferences based on their senses – think about your own. How often do you feel you need to wear sunglasses? Are there any textures that you just can’t stand to touch?

Preferences are often based on being 'hyper-' or 'hypo-' sensitive to something. 'Hyper-sensitivity' means overstimulation via a particular sense. 'Hypo-sensitivity' means understimulation.

How can I tell what my child's preferences are?

If being mindful of the senses is the first step, the next step is being able to spot sensitivities in your child to understand what they like and don’t like.

Lucy suggests some ways that you might spot your child's sensory preferences…

Taste: Preference for certain flavours. Perhaps they have a strong like or dislike for strong or bland flavours.

Sound: Sensitivity to loud noises. Perhaps they might dislike hearing people eating.

Sight: Tends to refuse foods just on appearance. Maybe they're averse to bright lights in the room.

Touch: Not wanting to get their hands or face messy.

Smell: They may be disgusted by strong smells – it could be food, public toilets, butchers’ shops etc.

Interoception: They may be feeling fine one minute, then feeling intensely hungry - or ‘hangry’ - the next. They may seem overly tired or have sudden emotional outbursts.

Vestibular sense: They may struggle to sit up straight, or have poor balance when eating.

Proprioception: They may be a little clumsy or very active when it's time to eat, e.g. spinning, jumping, ‘bouncing off the walls’ or seeking lots of physical contact.

As Lucy says…

“A little understanding goes a long way.”

Noticing your child’s behaviour and recognising the signs of their sensitivity, whatever it might be on a given day, is a great tool for parents to have at mealtimes.

And, while it is true that everyone has sensory preferences, remember that neurodiverse children may experience more pronounced sensory preferences and issues around food.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed or unsure, try to set up an appointment with your GP to talk things through.

What can I do to help?

Once you have a good understanding of the senses and have begun to recognise your child’s preferences, you might start to think about making changes to help your child feel more comfortable – particularly during mealtimes.

Changing their preferences is an uphill struggle, Lucy explains, so instead you may think about how you can change their environment or your food choices. Here are her top tips for each sense…

Taste: Notice if they like bland or strong flavours and change meals to cater to their range. If they like strong flavours, you could try pickles or mustard. If they like blander flavours, think about nutritional foods that have a weaker taste, like cucumber or oatmeal. Don’t be afraid to experiment!

Sound: Try playing soothing music during mealtimes or removing unnecessary noise – perhaps pause the washing machine while you’re eating. Also consider that some foods will be noisy in the mouth, like raw carrots, and your child might have a reaction to that.

Sight: Present meals or snacks in a child-friendly way. Perhaps they would prefer that there isn’t too much of a visual distraction during meals, like clutter or a TV on.

Touch: Ergonomic/baby cutlery can help prevent the need to touch food, if that overwhelms your child. Using a deep bowl can make it easier for little hands to use cutlery.

Smell: Open the windows and air out the kitchen after cooking. Put lids on food if it’s sat on the table or the side. Give your child a blanket or teddy sprayed with a smell they like, if they need it.

Interoception: A good routine is helpful. Aim for three meals and two snacks each day, trying to keep them as regular as possible.

Vestibular: Ensure your child is well seated at the table with good support. Try supporting their feet with a box or stop. Perhaps allow them to use their fingers to eat.

Proprioception: Allow movement breaks during meals if your child is restless. Maybe try a weighted blanket before or during mealtimes to calm nerves.

Lucy says that parents shouldn’t be too hard on themselves if they’re struggling to get their child to eat well consistently, as their food preferences can change on a daily basis.

At the end of the day, “the most important thing is to show your child that you understand and that you sympathise. Simply feeling heard and understood can help,” Lucy says.

“Recognise when your child may feel overwhelmed and acknowledge that they are less likely to eat if there is or has been a lot of sensory input in their day.”

Think about if your child may be struggling having been to a busy restaurant, or if you’ve just picked them up from nursery for example, and try not to be too disheartened.

What else is happening when my child is being fussy?

Remember that food issues are very rarely related to just sensory preferences – as Lucy explains…

“It’s just one piece of the puzzle.”

Other factors in fussy eating could include illness, life events, emotions and the effects of normal, healthy development.

If you are having problems getting your child to eat, and feel overwhelmed to the point that it is affecting everyday life, Lucy recommends speaking to your GP.