MAURICE BLIK:Yeah, this is looking good.

All the work for this show is all new work, and it’s a bit of a development really of the work I’ve been doing for the last thirty years or so.

I’m not one of these artists dying to get into the studio and make the next thing, it’s always been a struggle in a way to get around my initial feelings about making a sculpture.

I mean I have to go back to when I was in the camp and I had my little sister was born there, and err, she was coming up for her first birthday, and um, I mean, obviously as you can imagine, it wasn’t somewhere where you could go and get presents and things and food was very tight you know, very hard to get hold of and anyhow, it was coming up for her birthday, and I’d found a carrot which was a bit bent, and I made it into a little boat, I’d put little sticks for masts in it and I was gonna give this to her for her birthday and I, you know I was what, five and a half or something, and I’d kept asking my mother, you know is it her birthday now, and it wasn’t and soon, not now, soon.

So this build up to when her birthday was when I could give her, her present. And err, she didn’t get there, she didn’t’ make it to her birthday, you know she died and I couldn’t give her this present, and years later when I had therapy you know, Jean, the therapist said well this was your first sculpture and in a way that’s stayed with you ever since you know and consequently I’ve put down the fact that, that it was always a struggle for me, although I wanted to make a sculpture you know it was never a lovely experience, it was a struggle, it was a torment.

I could have been a miserable depressing character that oh, you know, I’ve had an awful start in life, woe is me, but I’ve taken the opposite view in a sense and said you know, you tried to wipe me out, but it didn’t happen so here I am, and take note. I mean, maybe that sounds a bit triumphal but I don’t mind.

My son made an observation, and he said you know your father would have wanted you to enjoy your life and be happy and I think he was right in making that observation.

The struggle I’ve had is partly to do with, well I’m sure you’re familiar with the sort of guilt of surviving that many, not just survivors of the Holocaust, but many people who survive awful tragedies and one thing and another but they feel guilty about, um, having survived and I suppose what my son was saying, don’t feel bad. And err, yeah I think he’s right, I think you know, don’t feel bad about surviving.

Video summary

Internationally renowned sculptor Maurice Blik talks about how his experience as a 5-year-old in Bergen-Belsen has influenced him and his work.

Building towards his new exhibition, he recounts the moment when his baby sister died in the camp.

Almost 40 years after Maurice started sculpting, he is only just coming to terms with how this experience during the Holocaust has influenced his life and the choices that he has made. He has recently started to understand that sculpture has been a way of working through his experiences of the Holocaust. He explains how, in the past, the process of sculpting has felt tortuous as a result of this.

Maurice emphasises the importance of doing something that has meaning, and which helps him to feel he is leaving his mark. He also discusses the lasting feelings of guilt that are associated with surviving.

Maurice Blik was born in Amsterdam in 1939 and was deported to Belsen with his mother and two sisters. His younger sister Millie and father were both killed in the Holocaust. As well as Belsen, Maurice survived Westerbork concentration camp.

Maurice is an internationally renowned artist. He was a past president of the Royal British Society of Sculptors and has been awarded honorary US citizenship as ‘a person of extraordinary artistic ability’.

This clip is from the BBC series, The Last Survivors.

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter, we strongly advise teacher viewing before watching with your students.

Teacher Notes

Discuss how Maurice has used art as a way to process his trauma and to heal.

Why might people feel guilty when they survive something terrible?

For years Maurice didn’t want to be defined by his experiences but ultimately, he couldn’t escape them. Do you think that this is always the case?

Maurice survived the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen. Use his experience as a way to learn about what type of camp Belsen was and what happened there.

This short film will be relevant for teaching history at GCSE and above in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and National 4/5 and above in Scotland.

Frank Bright recounts the fate of his former classmates. video

Frank Bright discusses his work researching the fate of his former classmates, using a class photograph taken in 1942 which he calls ‘Red for Dead’.

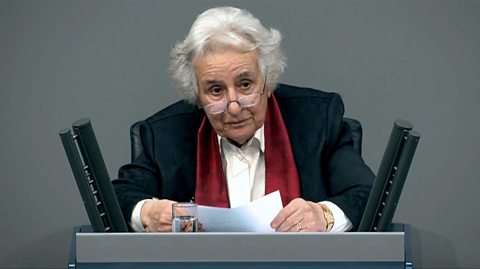

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch addresses German Parliament. video

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch addresses German Parliament to caution against forgetting the past. She contemplates as to what difference speaking out as a survivor can make.

Manfred Goldberg confronts the death of his brother. video

Manfred Goldberg returns to Germany for the first time since he was a child in 1946 to attend a memorial for his family. In doing so, he finally acknowledges the death of his brother.

Ivor Perl returns to Auschwitz with his daughter. video

Auschwitz survivor Ivor Perl returns to the camp with his daughter Judy for the first time. She’s asked Ivor to return in the hope that it will help him, and therefore her, come to terms with the past.

Sam Dresner grapples with his memories of the Holocaust. video

Sam Dresner has no photos of his family, who were murdered when he was a boy. He uses art to recreate what they looked like from memory, and to try and process what he saw.