The story of how hip hop embraced horror

By Ian McQuaid, 31 October 2018

Halloween and rap have a long shared history. From Nas sampling the theme from The Amityville Horror (on I Am…’s Album Intro) to Dr. Dre paying homage to John Carpenter’s Halloween score (on Murder Ink from 2001) right the way through to Snoop Dogg starring in B-movie horrors and Skepta's recent tradition of dropping All Hallow’s Eve-themed treats.

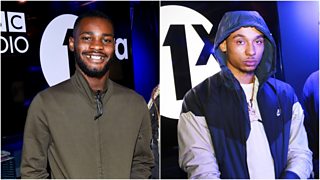

To get you in the spirit for Halloween, 1Xtra has a spooky Annie Nightingale special, Dotty's Trick or Treat edition of A-Z Roulette runs all week on the Breakfast Show and there’s a Halloween mix from MistaJam.

But it's not only Halloween. As a whole, hip hop and horror have gone together since the genre’s very beginnings, with many rappers drawn to its gore, sensationalism and outsider status.

From the genius of Thriller to novelty horror-rap...

Hip hop's first spooky twist arrived in the 80s, and was inevitably influenced by the towering presence of Michael Jackson's Thriller. Jackson changed the face of pop with his iconic video – featuring a feast of zombies, werewolves and the gleeful cackle of B-movie icon Vincent Price - and set the pace for an entire generation.

Some rappers responded with a more tongue-in-cheek take on the genre. A year after Thriller landed, electro-rap pioneer Whodini dropped The Haunted House of Rock in 1983, a synth-heavy jam that imagined the Creature From the Black Lagoon spitting bars to The Addams Family. Five years later, a pre-Fresh Prince of Bel-Air Will Smith put out A Nightmare on My Street, a homage to quintessential 80s horror villain Freddy Krueger, while 1988 saw comedy-rap trio the Fat Boys provide the ultimate schlock-horror rap hybrid by recording Are You Ready for Freddy for the official soundtrack to A Nightmare on Elm Street 4, featuring creaky bars from Krueger himself.

Warning: Third Party video may contain adverts.

The birth of horrorcore...

Amidst all of the novelty horror-rap, something a bit more transgressive was bubbling under the surface, with the sub-genre now known as horrorcore owing its origins to this period. In 1987, Dana Dane’s Nightmares dispensed with lyrics populated with the beasts of Hollywood horror folklore, and instead turned inward, placing himself at the heart of a terrifying situation - a man pursued by his nightmares.

Meanwhile, over in Detroit, another young rapper named Esham was taking a similar route. On tracks like Devil’s Groove from his 1989 debut Boomin Words from Hell, Esham sampled the classic, haunting piano loop from The Exorcist to provide a backdrop for rhymes about the cold, immoral and doomed mind of a "psychopath" who was “smooth like Satan”.

Speaking to Detroit’s Metro Times, Esham later explained that he was attracted to horror tropes, more often found in heavy metal and rock than rap music, because it reflected "the turmoil that our city was going through at the time". He added: "We referred to the streets of Detroit as 'Hell' on that record. So that's where my ideas came from."

The Geto Boys and Gravediggaz

This switch in emphasis - from lyrics full of drive-in monsters to bars that used horror as an analogy for societal and personal ills - started to gather pace as the 90s rolled in. As a lyrical device, it allowed rappers to make hard-hitting comments on the state of America, while also providing the visceral thrills and spills of blockbuster entertainment. This was most realised on 1991’s Mind Playing Tricks on Me by the notorious (and lyrically controversial) Geto Boys. On that particular track, the Houston trio (Scarface, Willie D and Bushwick Bill) describe a man haunted by the ghosts - real or imagined - of his deceased rivals. It remains one of hip hop’s most chilling moments.

Following in the Geto Boys’ footsteps were Gravediggaz, a New York supergroup that saw Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA join forces with De La Soul producer Prince Paul and rappers Poetic and Frukwan. All four performed with horror-themed alter-egos: Prince Paul was 'The Undertaker', Frukwan was 'The Gatekeeper', Poetic became known as 'The Grym Reaper' and RZA was the pun-tastic 'The RZArector', and over the course of four albums they teamed classic boom-bap beats with darkly comic lyrics that were deliberately shocking with a satirical edge. Writing of their 1994 debut 6 Feet Deep at the time, Q Magazine noted how "the foursome use death, burial and The Grim Reaper as central themes for a chilling mid-tempo stomp through America's urban problems."

Horrorcore's rise, fall and revival

As Gravediggaz gained prominence, we began to see more mainstream artists take influence from the horrorcore genre: Kool Keith in his Dr Octagon guise recording a surreal concept album about a ghoulish doctor-turned-murderer, and an early-career Eminem describing himself as "a mixture between [Marilyn] Manson, Esham and Ozzy [Osbourne]" on his 1999 debut The Slim Shady LP. Elsewhere, Insane Clown Posse took a more cartoonish route, gaining scores of fans (or Juggalos, as they’re proudly known) with their killer-clown aesthetic and supernatural-inspired lyrics that centre around the Dark Carnival, a self-mythologised limbo where lives are judged before passing into the after-life.

After laying low for most of the following decade (in 2007, Rolling Stone labelled horrorcore as a "short-lived trend, which generated more schlock than shock"), macabre themes returned to rap around the turn of the 2010s, with Tyler, the Creator’s early mixtapes and the witch house genre, which saw acts like Salem and Pictureplane mixing occult themes with hazy, chopped-and-screwed trap beats. Even Kanye West took inspiration from classic horror imagery for 2010’s posse-cut Monster, with a video that included zombies, corpses, Nicki Minaj dressed as a vampire and Rick Ross triumphantly rapping "I’m a monster, no good blood sucker" - the latter lyric operating as a sort of badge of honour response to the vilification of rap stars in the press.

A golden age of macabre rap?

Horror-inspired rap is now once again finding prominence. There’s the dark nihilism of US rappers such as Lil Uzi Vert, who regularly cites Marilyn Manson as a major influence and plays freely with Satanic symbolism. He has in the process angering both Christian critics and Migos' Offset, who clashed heads with Lil Uzi last year after the Philadelphia wore a necklace depicting an upside-down cross). The video for Uzi’s 2017 breakthrough single XO Tour Llif3 also paid extensive homage to horror movie and slasher flicks, with graveyard scenes and baths full of blood shot by Blair Witch Project-like handheld cameras.

But Lil Uzi is just the tip of a growing iceberg of rappers draping themselves in gothic imagery that draws on everything from survival horror games, such as Resident Evil, to dark fantasy anime, and modern horror movies. You have Denzel Curry, whose Clout Cobain video depicts a twisted circus, and New Orleans' $uicideboy$, a group whose lyrics are full of references to cults, violence and death. In the UK, we’ve seen artists coming through like Scarlxrd, who combines the aesthetics of anime and horror with skull-crushing bass, not to mention his song named after modern dystopian horror classic The Purge, as well as London newcomer Ali3nhead, who splices his unsettling trap ballads with explosions of energy that pounce like slasher-flick jump scares.

But what attracts hip hop to horror?

It makes sense that the worlds of hip hop and horror should collide so often. Rap, much like horror movies, is a genre often comprised of amped-up entertainment and larger-than-life personas. But it goes deeper than that too. Hip hop is historically a genre born out of hardship and the violence and suffering abound in horror often provides a perfect analogy - and catharsis - for real-life turmoil and trauma. It’s little surprise that morbid iconography and themes of death and decay have informed the music and lyrics of many.

When Uzi Vert sings "all my friends are dead" on XO Tour Llif3, it perhaps has more in common with the introspection of 80s indie-goth icons such as Bauhaus and The Cure than it does with the shock-horror of the likes of ICP. Instead, it's representative of a new generation using morbid themes to explore real-life horrors.