How Australian outback artist Albert Namatjira found fame and became an icon for indigenous rights

22 August 2022

In James Fox's series Oceans Apart, the art historian traces the momentous impact of the west's contact with the cultures of the Pacific. In the first episode, pioneering artist Albert Namatjira's outback visions set in motion a cultural revival that ultimately re-imagined Australia. His celebrity also challenged mainstream Australia's ideas about how indigenous people should be treated.

In Art of the Pacific with James Fox, the episode on Australia focuses on the country's indigenous culture, the world's oldest continuous society. A painter from that culture had a profound influence beyond the artistic world - Albert Namatjira's ultimately tragic story was the “the beginning of a recognition of Aboriginal people by white Australia.”

In 1900, there was no place for Aboriginal people in the story of modern Australia and its art. But that began to change, and in an unlikely place. Australia’s Western Desert is a vast, arid landscape in the country’s interior. In this supposedly barren landscape the seeds of an Aboriginal revival were sown; an artistic revival that would first be recognized in Australia, and then around the world.

In the supposedly barren landscape of Australia's Western Desert, the seeds of an Aboriginal art revival were sown.

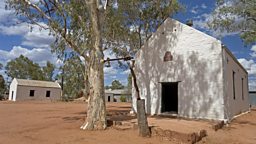

This revival began in Hermannsburg, a small Aboriginal settlement 80 miles from Alice Springs. At the village's centre stands a Lutheran mission that, starting in 1877 and in return for religious conversion, offered indigenous people accommodation, education, and some protection from white settlers.

Elea Namatjira was born at the mission in July 1902 and grew into a studious young man. He worked as a carpenter, blacksmith, stockhand and camel driver. Mission life was very unlike that lived by Elea's people in the deserts of the Northern Territory. That was a lifestyle he knew little about, until at the age of thirteen he experienced an important Aboriginal ritual – initiation.

As one of the Aranda or Arrernte group, he lived in the bush for six months and was taught traditional laws and customs by tribal elders. His work as a camel driver also took Albert through the country he would later paint, the dreamtime places of his people.

Namatjira's aspirations changed with the 1934 visit of two exhibiting artists, Rex Battarbee and John Gardner. Elea became transfixed by the paintings on view, and determined to produce similar works himself. He asked his mission's pastor for some watercolours, and when the small box finally arrived he began making his first paintings.

Namatjira’s work was soon being exhibited in Australia's great cities - Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide.

Two years later Battarbee returned on a painting trip. Elea acted as his guide to the scenic areas and Battarbee gave him tuition in the principles of landscape painting. Elea quickly developed his own style and began signing pictures ‘Albert Namatjira’, his baptismal name at the mission.

Battarbee featured three Namatjira paintings in his 1937 exhibition in Adelaide, and arranged a solo show in Melbourne the following year. The Australian public was captivated, and next came sold-out events in Sydney and Adelaide.

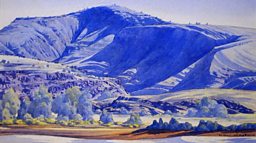

James Fox: “This painting (above) is Mt Hermannsburg, the great guardian mountain that towers above the village in which Albert Namatjira was born. He has tried to capture the low, milky light that transfigures this arid landscape into a kaleidoscope of hues. The mountain becomes an irresistible pattern of blues, teals, turquoises and purples.”

Namatjira was now famous, and in 1954 he was introduced to the young Queen Elizabeth II in Canberra.

Namatjira’s paintings have divided opinion. They were thought by some to be sad symbols of Aboriginal assimilation. The Art Gallery of New South Wales states that Namatjira’s landscapes have since been “re-evaluated as coded expressions on traditional sites and sacred knowledge”. They can stand as powerful hybrid artworks - a Western-style vision of Australia that no Westerner could have produced.

What’s certain is that by the 1950s they had made him famous, with Namatjira reproductions adorning the walls of middle-class living rooms across Australia. He was awarded the Queen's Coronation Medal in 1953, and the following year he met the young Queen Elizabeth in Canberra.

James Fox examines three key Namatjira watercolours

James Fox on the paintings of Albert Namatjira

Three key Namatjira watercolours, housed at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

The Australian public was unhappy that one of its favourite artists was treated like a second-class citizen, unable to vote or own property, and Namatjira began to speak out, telling a local newspaper in 1952: “I think I should have full rights. I am 50 years old now and there are many things I would like to do and can’t without citizenship rights.”

Here was an Aboriginal man imprisoned for an activity - drinking with a relative - which was not a crime for any other Australian.

In 1957 Albert Namatjira became the first Aboriginal person to be granted full Australian citizenship. As well as vote and build a house for his family, he could now legally drink alcohol, unlike his friends and relatives who came under the Welfare Ordinance.

A tragic event occurred when a young woman died at a party at Namatjira’s camp at Morris Soak in Alice Springs; the acclaimed artist was later charged with supplying alcohol to an Aboriginal person - the victim's husband, one of the artist's relatives, had discovered a bottle of rum in Albert's car - and sentenced to six months at Papunya Native Reserve.

Douglas Lockwood, a journalist on Melbourne paper The Herald, remarked: 'In my 20 years experience... I have never witnessed a more deeply moving drama. Albert was a heartbroken old man, bewildered by events for which, so it was implied, he was to blame'.

Here was an Aboriginal man, an example of the government's assimilation policy in action, who was imprisoned for an activity - drinking with a relative - which was not a crime for any other Australian. Newspaper stories referred to a man ‘caught between two civilisations’, while the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement wrote to editors pointing out that actually it was a case of a man trapped by laws which had to be changed.

Namatjira was reunited with his wife of 38 years after two months, but he had lost his desire to paint. In a sad turn of events, Albert had a heart attack in 1959, and died of heart disease complicated by pneumonia less than a year after his release. There were many expressions of shock from the public.

While in hospital shortly before his death, Namatjira gifted his mentor Rex Battarbee three of his paintings. And he left a further legacy, as throughout his life he had encouraged family and friends to take up painting. They are still doing so today. James Fox says,

Like Albert, Namatjira’s grandchildren have a rare ability to capture the vivid colours of the Australian desert.James Fox

“I accompanied Albert Namatjira’s grandchildren on one of their regular watercolour trips near Alice Springs. Like Albert before them, Namatjira’s descendants seem to have a rare ability to capture the vivid colours of the Australian desert. And I have seen first-hand how important art has become to them.”

Namatjira’s artworks now hang in just about every major gallery in Australia, and him and his paintings have featured on many of the country's postage stamps.

Other Aboriginal artists would do something completely different. Watch the first episode of Oceans Apart: Art and the Pacific to discover how Aboriginal motifs have come to symbolize modern Australia itself.

- A version of this article was originally published in 2018.

Oceans Apart: Art and the Pacific with James Fox

![]()

The beginning of Australia's indigenous art revival

How Australian outback artist Albert Namatjira found fame and became an icon for indigenous rights.

![]()

Episode one: Australia

James Fox argues that Aboriginal people are recolonising Australia with their imaginations.

![]()

The Pursuit of Paradise: Paul Gauguin

Eight paintings tracing Gauguin's quest for the exotic in Tahiti.

![]()

Episode Two: Polynesia

How the West has created a myth of Polynesia as a paradise.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms