The Pursuit of Paradise: Eight paintings tracing Paul Gauguin's quest for the exotic in Tahiti

26 August 2022

Paul Gauguin's quest for artistic purity in Tahiti produced great work that influenced countless artists and movements. At the same time it cemented the western myth of a paradise with women available to be exploited. James Fox continues his exploration of the collision of the West and Pacific culture in Oceans Apart on BBC Four and iPlayer, as he journeys across Polynesia.

Paul Gauguin needed a miracle. It was 1890 and his wife had abandoned him, taking their children too. Vincent van Gogh, his old friend, had killed himself. His career as an artist had stalled, and he was penniless. So he hatched a plan, which he announced to his estranged wife in a letter.

May the day come... when I can flee to the woods on a south sea island, and live there in ecstasy, for peace and for art.Paul Gauguin, 1890

“May the day come... when I can flee to the woods on a south sea island, and live there in ecstasy, for peace and for art. With a new family, far from this European struggle for money. There, in Tahiti, in the silence of the lovely tropical night, I can listen to the sweet murmuring music of my heart, beating in amorous harmony with the mysterious beings of my environment.”

The artist had bought in to an old myth about Polynesia that went all the way back to the time of Captain Cook. A tropical paradise. A land in which the living was easy... and so were the women. In March of 1891, Gauguin boarded a ship called the Oceania and left Europe behind, forever, he hoped.

Three months later the Oceania docked in Papeete, the Tahitian capital. But it felt much closer to Europe than he had anticipated. It was filled with French people, French buildings, French newspapers. And very expensive French wine.

Bit by bit, step by step, civilisation is peeling away from me’Paul Gauguin

He moved out to the countryside, where he built a traditional hut with reed walls and a thatched roof. Gauguin was gradually fashioning his own fantasy paradise. He learned a few words of Tahitian and got to know his neighbours. He walked around naked a lot of the time. ‘Bit by bit, step by step’, he wrote, ‘civilisation is peeling away from me’.

This immersion in the culture of Tahiti, whether authentic or mostly imagined, inspired a number of intoxicating paintings.

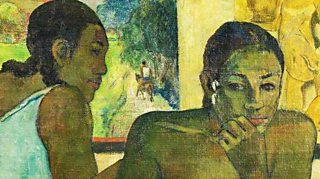

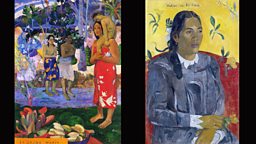

Early Tahitian paintings, 1891-1892

Ia Orana Maria means ‘Hail Mary’ in the local language, and it was Gauguin's first major Tahitian canvas. Painted in 1891, it shows the Virgin Mary and the young Christ as Tahitians, surrounded by bare-breasted worshippers and ripe fruit.

And Vehine no te tiare, Gauguin's first Tahitian portrait painting, shows a beautiful woman staring evocatively into the distance as exotic flowers rain down around her. The sitter insisted on wearing her Sunday best: a European-style dress normally reserved for church.

Both of these paintings capture Tahitians at a crossroads between old and new, the indigenous and colonial cultures. But Gauguin was establishing a new style that still resonated with his surroundings – rich colours, decorative patterns, and of course mesmerizing female subjects.

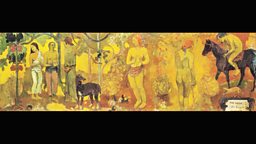

Faa Iheihe, 1898

On Art UK's page for this work, it states, “It seems to represent an earthly paradise of men and women in harmony with nature. Indeed, it has sometimes been subtitled 'Tahitian Pastoral'.

Gauguin wrote in 1898, 'Each day – my latest important paintings attest to this – I realise that I have not yet said all there is to say here in Tahiti... whereas in France, with all the disgust I feel there, my brain would probably be sterile; the cold freezes me both physically and mentally, and everything becomes ugly to my eyes.'”

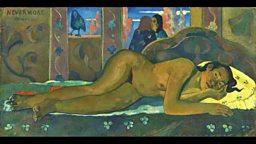

Nevermore, 1897

Gauguin's interests went beyond the aesthetic. James Fox: "Like so many Europeans before him, he took advantage of the local women. He slept with innumerable locals over the course of two visits to Tahiti. He married three of them: one was thirteen years old, the other two were both fourteen. He abandoned one, had children with two, and he infected all three with syphilis."

"He depicted one of these wives in this extraordinary picture, Nevermore."

Nevermore, 1897 by Paul Gauguin | Photo credit: The Courtauld Gallery, Art UK

The public voted Nevermore the most romantic painting in Britain... as far as I'm concerned this painting is deeply, deeply disturbing.James Fox in Oceans Apart

In Oceans Apart's second episode, James Fox views Nevermore at The Courtauld Gallery in London: “This is a portrait of Ahura. Gauguin married her when she was 14 years old. When she was 15, a few months before this painting, she gave birth to his daughter. Tragically, the baby died after only a few days, and Ahura understandably sank deep into depression.

“Her eyes, which look swollen from tears, stare hopelessly into space. But what I find particularly touching, and also quite alarming, is how young she looks. She is reacting to this tragedy not as a woman, but as a girl. After all what do teenagers, 15-year-olds, do when they get bad news. They run up to their bedrooms and slam the door, they collapse onto their bed and they curl into a ball. That is precisely what Ahura is doing.

“But this painting in truth isn't really about her. Paul Gauguin’s art is always about Paul Gauguin. In 1897, he too was suffering from depression and this image is drenched in his own misery. The murky colours, the bright red fabric that pulsates like blood, the skulking women in the background gossiping, or perhaps even plotting.

“And, most unsettling of all, the large malevolent bird perched on the window ledge staring down at the grief-stricken girl and cursing her and him for eternity.

“Gauguin doubtless got his idea from Edgar Allan Poe's famous poem, which describes a raven appearing one night at the author's home and tapping at his bedroom door. The only thing the raven ever said, over and over again, was ‘Nevermore’.

“A few years ago, the public voted this the most romantic painting in Britain. I cannot for the life of me understand how they reached that conclusion, because as far as I'm concerned this painting is deeply, deeply disturbing.”

- Further reading: The Tahitian woman behind Paul Gauguin's paintings, by Tiare Tuuhia | ArtUK.org

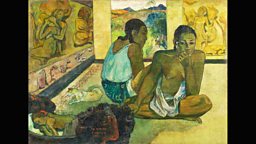

Te Rerioa, 1897

From the Art UK page for this painting: It shows two women watching over a sleeping child in a room decorated with elaborate wood reliefs. The figures do not communicate, heightening the sense of mystery.

Gauguin meant this subject to be unclear. He wrote: ‘Everything is a dream in this canvas: is it the child? is it the mother? is it the horseman on the path? or even is it the dream of the painter!!!’

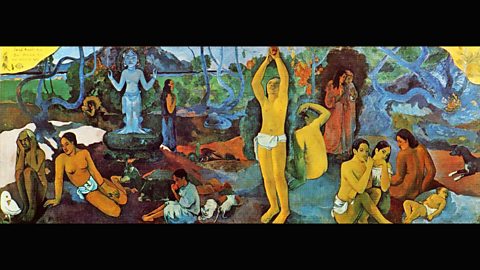

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, 1897

This darkness had begun to pervade all of Gauguin’s life. By the time he painted Nevermore he was increasingly unhealthy. He felt his life was coming to an end. In the same year, he made his most ambitious Tahitian painting.

In English it is is called Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? Watch James Fox analysing this work.

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

James Fox examines Paul Gauguin's masterpiece.

This painting was the culmination of Gauguin’s personal mythology. Almost four metres wide, when read from right to left it describes the cycle of life from infancy and youth, through to maturity, old age. And finally the world that lies beyond death, as embodied by the blue idol.

Gauguin wrote: ‘I believe that this canvas not only surpasses all my preceding ones, but that I shall never do anything better’.

James Fox: “It is a hybrid masterpiece: an unforgettable combination of ancient and modern, Oceania and the West. But this paradise contains the seeds of its own corruption.

“Shortly after completing Where are we going?, Gauguin tried to take his own life by arsenic poisoning in the hills above his village. He drank too much of it and simply ended up making himself horribly sick. He was treated in the local hospital after he made it back to town.

Paul Gauguin was a complicated person, and his time spent in the Pacific was particularly controversial.James Fox

“His life dragged on for another six years, spending the final two elsewhere in Polynesia. He died in May 1903, never returning to Europe again.

“Gauguin was a complicated person. And his time in the Pacific is particularly controversial.

“Some people think he was a noble explorer, one of the first people to properly engage with Polynesian society and culture on their own terms. But others think he was a seedy sex tourist. A man who objectified and exoticized this part of the world for his own ends. It is, as ever, a bit of both.

“But one thing I think is certain. Gauguin reinvigorated the old myth of Polynesia for the modern age.“

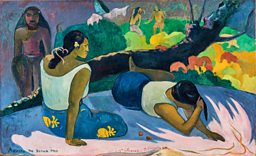

Areazea no Vazua ino, 1894

Watch the second episode of Oceans Apart to find out more about how these islands were re-imagined, from the Arcadian landscapes depicted by Cook's on-board artist William Hodges, through the art of Paul Gauguin and on to the tacky holiday idyll of modern Hawaii.

And how some indigenous artists are fighting back, reviving the traditional cultures of Polynesia and using art to protest against the objectification of its women.

Art UK

![]()

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin paintings in the Art UK collection.

Oceans Apart: Art and the Pacific with James Fox

![]()

The beginning of Australia's indigenous art revival

How Australian outback artist Albert Namatjira found fame and became an icon for indigenous rights.

![]()

Episode one: Australia

James Fox argues that Aboriginal people are recolonising Australia with their imaginations.

![]()

The Pursuit of Paradise: Paul Gauguin

Eight paintings tracing Gauguin's quest for the exotic in Tahiti.

![]()

Episode Two: Polynesia

How the West has created a myth of Polynesia as a paradise.

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms