Alfred Hitchcock: Murder, mayhem...and music

Matthew Sweet | 15 August 2015

As a successful director, Alfred Hitchcock got the pick of Hollywood's finest composers. And, as MATTHEW SWEET shows, knew exactly what he wanted from them. Unsurprisingly, their creations have become some of the most famous - and well-loved - scores ever recorded. In a special concert the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, under the baton of Timothy Brock, brings them thrillingly to life.

Matthew Sweet | 15 August 2015

In 1976, an old director and a young composer ate lunch in a small office at Paramount studios. The director had steak and a bottle of red wine. The composer nibbled salad. The talk was not of the film they were making together.

Instead, they discussed their shared enthusiasm for contemporary music – about which, the young composer soon realised, the old director knew far more than he. Once lunch was over, it was back to work on Family Plot. For Alfred Hitchcock, the last line in the filmography. For John Williams, an intermezzo from his early period, between Jaws and Star Wars.

Has any director understood the power of music more completely than Hitchcock?

The Sound of Hitchcock performed by the BBC SSO

The Composers

Think of the scene from Young and Innocent, when the camera moves through a crowd of dancers to find the eyes of a blackface swing-band drummer, whose twitching eyes reveal a murderous secret.

Or the discordant electronica that amplifies the horrors of The Birds – and is the nearest thing offered to an explanation of their savagery. Or the weird howl of the Theremin on the soundtrack of Spellbound.

But he didn’t formulate all these on his own – Hitchcock developed his musical intelligence in conjunction with some of the screen’s greatest composers.

Franz Waxman

Waxman and Hitchcock both went west to avoid the Nazis – though only Waxman was beaten up by them on the streets of Berlin.

His first score for Hitchcock was a landmark – not just for its shivery Novachord weirdness, but for its life beyond the screen – the Rebecca suite was one of the first Hollywood scores to be broadcast on the radio, sold on disc and performed in the concert hall.

There were three more collaborations. For Suspicion, Waxman crafted a theme that seemed to agree with the dark speculations of its heroine – the musical equivalent of the light bulb Hitch placed inside the doubtful glass of milk that Cary Grant offers to his bride at the climax of the picture.

For The Paradine Case Waxman produced a neurotically restless piano rhapsody. The score for Rear Window was another revolution: a mash-up of jingles and pop ballads that issued from the radios owned by the apartment-block residents spied upon by James Stewart’s immobilised hero, plus an original number, constructed in the course of the action by one of the characters – a songwriter played by Ross Bagdasarian.

The complexity of the exercise seemed to exhaust both director and composer, who never worked together again. “I had a motion picture songwriter when I should have had a popular songwriter,” Hitchcock told Truffaut in the 1960s. A parting shot, delivered a decade after the parting.

Miklos Rozsa

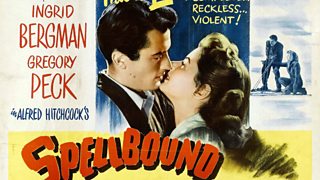

The Hungarian master Rozsa won an Oscar for his only work with Hitchcock: Spellbound – a thrilling and preposterous film set in a sanatorium where Ingrid Bergman plays a doctor who begins to have her suspicions about a new member of staff, played by Gregory Peck – a man with a morbid fear of black parallel lines.

Hitchcock commissioned Salvador Dali to produce a sequence in which we see the images that burn inside the mind of one of the characters – and Rozsa’s score proceeds at a similarly hysterical pitch. A Theremin haunts the work – which by 1945, already coded for the weird and the otherworldly.

Roy Webb

Roy Webb adored the darkness – or so his CV suggests. He spent many years at RKO crafting atmospheric scores for films noir such as Murder My Sweet and Crossfire and Build My Gallows High.

In 1961 a house fire robbed Webb of his entire archive and reams of unperformed manuscripts.

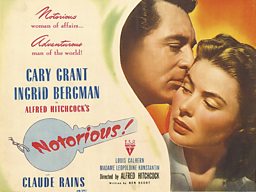

He was a protégé of the composer Herbert Stothard, who invited him to Hollywood to orchestrate an early Technicolor talkie called Rio Rita. That interest in Brazilian rhythms came in useful in 1946, when Webb was assigned to Hitchcock’s Notorious, in which Cary Grant’s Agent Devlin recruits Ingrid Bergman to infiltrate a Nazi spy ring in South America – which is led by Claude Rains, a Hitler-loving mummy’s boy whose wine cellar is full of uranium-packed champagne bottles.

It’s as much a love story as a spy-thriller – Webb was as emphatic about the romance as the mystery and intrigue.

Notorious was Webb’s only score for Hitchcock. If the director considered employing him again in later years, the request would have fallen on deaf ears. In 1961 a house fire robbed Webb of his entire archive and reams of unperformed manuscripts.

Despondent, he never composed another note.

Dimitri Tiomkin

Dimitri Tiomkin had a catchphrase – “don’t hate me.” It was something he said to directors who were about to hear a painful truth.

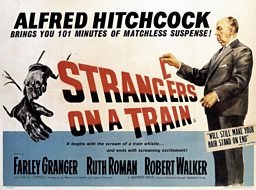

Strangers on a Train, however, may be Tiomkin’s Hitchcock masterpiece.

Tiomkin knew what he was talking about – he’d been putting music to film images since the early years of the Russian revolution, accompanying films by Eisenstein and Pudovkin.

He’d lived, too – his musical career took him from the Homeless Dog café in Tsarist St Petersburg, to the Weimar-Era Berlin Philharmonic to the recording studios of MGM and Universal.

His Hitchcock scores show a similar adaptability. The music of Shadow of a Doubt is founded on a waltz that reflects the punishing singlemindedness of the plot.

Dial M for Murder incorporates the ringing of the telephone into its elegant structure. Strangers on a Train, however, may be Tiomkin’s Hitchcock masterpiece.

The plot concerns two men hope to commit a perfect crime by exchanging murders. (“Criss-cross!” enthuses Farley Granger’s silky conspirator.) The music follows the same pattern, with motifs for its characters competing in a brash, frenetic score.

Bernard Herrmann

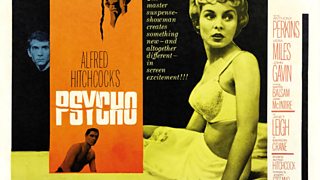

Imagine the Psycho shower scene without those strings. Tough, isn’t it? But Hitchcock found it easy. He wanted Janet Leigh attacked without assistance from the orchestra, as Cary Grant had been in the crop-duster scene from North by North West.

His violins seem as much the murder weapon as Norman Bates’s carving knife

But Bernard Herrmann composed some anyway, and now his violins seem as much the murder weapon as Norman Bates’s carving knife.

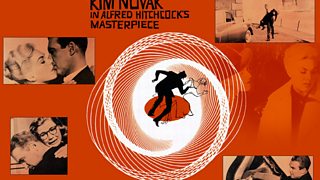

Herrmann had been Hitchcock’s collaborator since 1955. He had unlocked the black humour of The Trouble with Harry, accelerated the breathless pace of North by Northwest, intensified the agonised yearning of Vertigo with a score that borrowed with dignity from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde.

He was even permitted his own Hitchcock cameo: in the American remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, Herrmann is the LSO conductor whose Albert Hall performance of Arthur Benjamin’s ‘Storm Clouds’ cantata provides cover for an assassination attempt.

In 1966, however, their relationship received a mortal wound. The director listened to the prelude Herrmann had written for Torn Curtain, and declined to listen further, sacking him on the spot.

The music wasn’t what Hitchcock had requested. Neither was the shower scene. But by this time, Hitchcock had lost his appetite for the fait accompli, and instead of smiling, he turned cold, and plunged in the knife.

Related Links

Sound of Cinema

More film from BBC Arts

![]()

Citizen Kane

Seven things you might be surprised to learn about Orson Welles' classic film.

![]()

Reconstucting reality

When documentary-makers recreate true stories, it can have an incredibly powerful impact.

![]()

British animation secrets

The ingenuity that defines contributions to the art form from the UK.

![]()

Game changers

The black actors, directors and producers who paved the way for the current generation.