Theatre of war: Liberian Girl at the Royal Court

29 January 2015

Between 1989 and 2003 the Civil War in Liberia saw over 200,000 people killed, a million others displaced into refugee camps, and over 15,000 child soldiers recruited into 'Small Boys Units'. First-time writer Diana Nneka Atuona's play Liberian Girl tells one teenage girl’s story of survival.

In the first of three special features on new works at the Royal Court Theatre, Diana and assistant director Roy Alexander Weise discuss the challenges of writing and performing the play. And below, journalist CLIVE MYRIE recalls his meeting with Liberia's feared former leader Charles Taylor while covering the conflict for BBC News in 1995.

WARNING: The following films and article deal with violent and shocking incidents from Liberia's history.

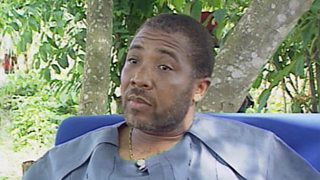

Charles Taylor was the quintessential African dictator, straight out of central casting. The mere mention of the warlord’s name would strike fear into the hearts of millions.

Now he's languishing in jail, with the trappings of head of state long stripped away. Ironically, what now plagues the country he used to rule, Liberia, is not war, bad government, repression, abuse of human rights, murder, rape, or torture - but the Ebola virus.

Charles Taylor was urbane, softly spoken and charming. He could afford to be. The menace of his rule came from others

Thousands have died because of it, but Charles Taylor, not so long ago, helped to kill many, many more.

When I met him in 1994 - my first foreign assignment for BBC TV - Liberia was in the midst of a vicious civil war.

President Samuel Doe was struggling to hold off a Libyan-backed rebel group called the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, led by the university-educated guerilla fighter, Charles Taylor.

The civil war was a struggle over power, ethnic and tribal loyalties and who should control the country's natural resources - including, of course, the diamond mines.

The war began in 1989, and five long years later the exhausted combatants seemed ready for peace. It was in this atmosphere that I flew to the capital Monrovia, for a meeting with a warlord.

Charles Taylor was urbane, softly spoken and charming. He could afford to be. The menace of his rule came from others, but crucially, on his orders. He promoted himself as the father of the nation, a benign guiding light, and this was the man I met in 1994.

I'll never forget his personal security detail. One in particular was so tall and large - not fat but muscular - that he seemed to block out the sun as he towered over Taylor seated before him.

Taylor had agreed to meet me and my cameraman on grassland outside his compound, as the African sun glowed. In the interview I raised the issue of human rights violations - torture and rape - in the war.

He looked me square in the eye and said: "Freedom is not free." In those four words he attempted to justify what had gone on, that the abuse of human rights was perhaps the price that had to be paid for a better tomorrow.

Three years later, with the war over, he ran for President with the election campaign slogan: "He killed my ma, he killed my pa, but I will vote for him."

Charles Taylor was telling the people, as he had told me, that freedom is not free. He won that election, in a landslide. But what exactly was the price to be paid for his lust for power?

On that 1994 visit to Liberia I came across a number of child soldiers. It's one of the many harrowing details of the civil war that children were not playing with toy guns, but the real thing.

They were given amulets - little polished stones, nothing valuable - and told they possessed the power to protect them in battle.

Clive Myrie reports from Liberia in 1995

A BBC News item on the civil war, including an interview with Charles Taylor.

Often, being so young, they were already fearless, with little concept of the consequences of their actions. That sometimes made them even more ruthless, cold and callous than the adults who'd terrorised them into going to war in the first place.

Children fighting in wars is not a new thing, but Charles Taylor took the concept to new levels

The children were lost innocents, who knew no better. As I've seen in other wars, the older fighters were often given drugs by commanders, leaving them high as they committed murder.

Some of the children were given drugs too, to help banish inhibitions - often cocaine or LSD. This made it even easier to rape, mutilate and torture.

Charles Taylor's malign influence didn't just cast a shadow over the land of his birth. In fact it was his meddling in the civil war in neighbouring Sierra Leone that eventually landed him in a human rights court, for what the presiding judge said was the "aiding and abetting as well as planning of some of the most heinous and brutal crimes recorded in human history".

He backed the rebel Revolutionary United Front in Sierra Leone with weapons in exchange for blood diamonds. He helped the RUF commit appalling atrocities including murder, abductions, torture and mutilation. He also helped in the recruitment of child soldiers, personally directing some RUF operations in Sierra Leone.

Children fighting in wars is not a new thing, but Charles Taylor took the concept to new levels. He helped develop the so-called Small Boys Unit as part of the RUF. At its height it numbered more than 10,000 children mostly, between the ages of 8 and 10.

More than half had been abducted from their families in RUF raids on towns and villages. The children were taken to special work camps where the boys were trained to fight, and often the girls became sex slaves.

One child soldier I met in Liberia could take apart and reassemble an AK-47 rifle blindfolded. This was often the first weapon they were given, because they're light and manageable.

During training, children were taught how to mutilate people, how to cut off limbs, lips, noses, even how to remove internal organs and make the victim eat them.

On raids in enemy territory if they came across a pregnant woman, they would try to guess the sex of the child, then use a machete to cut open the womb to discover who was right.

Charles Taylor became the first former head of state to be convicted and jailed by an international criminal tribunal since the Nuremburg trials of Nazi leaders in 1946. He's now serving 50 years in prison, and will die there. But what of the children he terrorised and brutalised, whose childhoods he destroyed?

Rehabilitation and re-education camps were set up to help the thousands who were brainwashed. Some have been reintegrated with their communities, but it's no easy task banishing the ghosts of war from the mind, and many have never recovered from the horrors they witnessed or took part in.

Many, inevitably, have mental health problems, are dependent on drugs and glue sniffing, their life chances diminshed. They're lost to the world, caged by their memories and nightmares - just as Charles Taylor is now caged in his cell.

About the play

Liberian Girl is at the Jerwood Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court until 31 January. It moves to the CLF Theatre, Peckham, from 3-7 February, and the Bernie Grant Arts Centre, Tottenham, from 10-14 February.

Cast

Soldier: LANDRY ADELARD

Double Trouble: MICHAEL AJAO

Anette: MARIÉME DIOUF

Amos/Commander: FRASER JAMES

Soldier: EDWARD KAGUTUZI

Killer: VALENTINE OLUKOGA

Finda: WERUCHE OPIA

Martha/Frisky: JUMA SHARKAH

Mamie Esth: CECILIA NOBLE

Creative Team

Director: MATTHEW DUNSTER

Assistant Director: ROY ALEXANDER WEISE

Designer: ANNA FLEISCHLE

Lighting: PHILIP GLADWELL

Sound Design: GEORGE DENNIS

Fight Direction: KATE WATERS

Dialect Coach: ZABARJAD SALAM

Related Link

More from the Royal Court

![]()

How to Hold Your Breath

An in-depth look at the theatre’s second highest-grossing show ever.

![]()

Fireworks

BBC Arts explores the Palestine-set play at the Royal Court Theatre.