Museum of the Mind: The art and history of 'Bedlam'

Shortlisted for Museum of the Year 2016

6 May 2016

The Museum of the Year award was created by The Art Fund to celebrate galleries and museums from all parts of Britain. In the second of a series of five articles on the institutions shortlisted for the 2016 prize, WILLIAM COOK visits the Museum of the Mind at Bethlem Royal Hospital. This is the psychiatric institution known in less enlightened times as Bedlam. The hospital's long-established museum, which was housed in a small building, was moved in 2015 to a fine Art Deco building on its campus. The space is used to explore the hospital's 700 year history, including its darker times, and also features work by artists who have suffered from mental health problems.

Museum of the Year shortlisted: Bethlem Museum of the Mind

The Bethlem Museum of the Mind shortlisted for the Art Fund Museum of the Year award.

Wandering around the leafy grounds of Bethlem Royal Hospital, it’s hard to believe you’re in the oldest psychiatric institute in the western world. The scenery is bucolic, the ambience is serene - yet in less enlightened times this place was better known as Bedlam, Britain’s most notorious lunatic asylum. Its splendid new museum shows how much things have changed.

There’s been a museum here at Bethlem for nearly half a century, but it used to be confined to a small, single storey building. There wasn’t nearly enough room to display the hospital’s historic archives - there was barely enough room for a dozen visitors at a time.

The Museum of the Mind doesn’t neglect Bethlem’s chequered past, but it’s not a chronological survey

However last year this museum was rehoused in a grand Art Deco building at the centre of this tranquil campus, visitor numbers are up from 2000 to 12000 per annum, and now it’s been shortlisted for the Art Fund’s Museum of the Year.

Bethlem’s illustrious history dates back to 1247, when the monastery of St Mary of Bethlehem was established in London’s Bishopsgate, devoted to the care of sick paupers. By the early 1400s, it had become a refuge for the insane.

In 1676 it moved to another site in central London, near Moorfields. Of those first two sites, nothing but two blue plaques remain. In 1815, the hospital moved south of the River Thames, to a palatial pile in Kennington.

In 1930 that bombastic building became the Imperial War Museum, and Bethlem moved to its current site, in the south London suburb of Beckenham.

The Museum of the Mind doesn’t neglect Bethlem’s chequered past, but it’s not a chronological survey – it’s a more impressionistic display. At the entrance are two weathered statues called Raving & Melancholy Madness, which stood outside Bethlem’s Moorfields site from 1676 to 1815.

Beyond them is a collection box, which visitors used to pass on their way out. ‘Pray remember the poor lunatics and put your charity into this box in your own hand,’ reads the inscription.

As the museum’s archivist Colin Gale explains, in the bad old days before the NHS, Bethlem used to depend on donations from visitors.

Some treated this hospital like a freak show. Others were more sincere. Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress ends with his anti-hero in Bedlam, but his portrayal of these ‘lunatics’ is sympathetic, not grotesque.

Sculptures at the Gates of Bedlam

Alastair Sooke examines the two sculptures that once adorned the gates of Bedlam.

The museum doesn’t shy away from the darker chapters in its story. There are chains and manacles on display, but they’re presented tastefully and discreetly.

There are intricate paintings by the Victorian artist Richard Dadd, whose work hangs in the Tate

This isn’t a chamber of horrors – it’s an assessment of how our understanding of mental health has evolved. ‘It’s a hospital, not a prison,’ says Colin, of Bethlem – the museum shares the same ethos.

There are testimonies from staff and patients, past and present, even comments from the visitors’ book. ’I am chasing my demons by visiting here,’ reads one. ‘It was a load of rubbish,’ reads another.’ ‘You’re all mad, not me.’

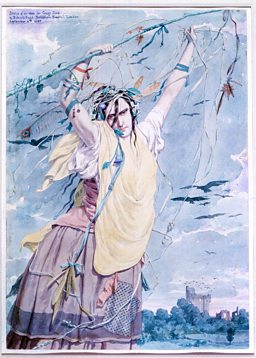

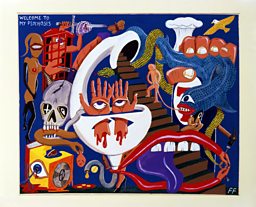

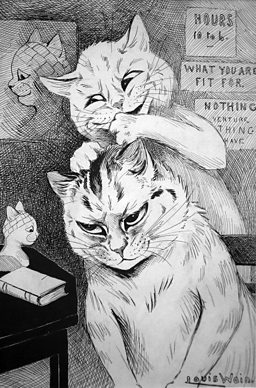

The most arresting exhibits are the artworks, made by patients. There are intricate paintings by the Victorian artist Richard Dadd, whose work hangs in the Tate (he was detained here after killing his father).

There’s a complex cityscape by Jonathan Martin (detained after trying to burn down York Minster). There’s an anguished self-portrait by Charlotte Johnson Wahl (a brilliant contemporary artist and – incidentally - the mother of Boris Johnson) who spent some time in the Maudsley, Bethlem’s sister hospital, in 1974.

But the Museum of the Mind is more than an art gallery – it’ll make you question your preconceptions about what madness really is. ‘We’re not telling people what to think – that’s not the point,’ says Colin.

Pepys, Swift and Dickens all visited Bedlam and wrote about what they saw. This museum invites you to follow in their footsteps, and make up your own mind.

This year’s Museum of the Year winner will be announced at London’s Natural History Museum on 6 July.

Museum of the Year 2016

![]()

The shortlist

Films featuring the five nominations

![]()

Victoria & Albert

A world-leading art and design museum with over 2 million objects from around the world

![]()

Jupiter Artland

A beautiful sculpture park and gallery near Edinburgh

![]()

Museum of the Mind

The new museum at Bethlem Royal Hospital, the western world's oldest psychiatric institute

![]()

Arnolfini Gallery

The ambitious art centre at the heart of Bristol's historic waterfront

![]()

York Art Gallery

The refurbished Victorian gem with a world class collection of British ceramics

Related Links

More from BBC Arts

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms