Eight-year-old Sylvia, in rural Tanzania, is determined to get an education and each school day makes a long and often risky one-and-a-half hour journey by foot - on her own - to school. Her family is poor and cannot afford to provide her with basic shoes for the walk or a good uniform. But she is considered lucky as it is estimated that 29 million primary school-aged children, more than half of them girls, are out of school in Africa.

Sylvia's mother remarried when she was young after her father died. The family lives more than 300km (nearly 200 miles) from the main city of Dar es Salaam. Their house is in the centre of the farming land - about half a kilometre from the nearest road. UN figures show that between 1999 and 2008 girls’ enrolment in Africa has increased from 54% to 74%, but about 16 million are out of school. Free primary education was introduced in Tanzania in 2001.

The school Sylvia attends is in a village 7km away. As she walks through the fields to get to the road, the terrain becomes more dense and turns into shrubland that cuts and scratches her legs and feet. She has to find a safe route avoiding snakes and other hidden dangers.

Sylvia walks this route in her flip flops, which offer no real protection in such terrain. Once they wear out, she will have to walk barefoot. She also has to be extra careful to keep her uniform clean as if it becomes too dirty, she will not able to attend school - she only has one shirt and skirt. Although her parents do not have to pay school fees, the cost of books and uniforms is always difficult.

Her journey then continues along a main road. In the searing heat of the dry season, choking clouds of dust from passing heavy vehicles and cattle engulf her. In the wet season, the road becomes almost impassable and the traffic showers her in mud. She sometimes has to wade through deep water that collects in the road because of the lack of drainage and the rising water table.

If she wants to avoid dangerous traffic on the roads, Sylvia can walk along the railway line towards her school, but this has its own dangers as trains often travel down the line and she is far more secluded on the railway. In more secluded areas, children are often approached by people offering lifts to school and are in danger of being kidnapped.

Her other option is to walk the old paths off the main road. As she gets older, these areas will become more dangerous as girls can be targeted for sexual abuse. Travelling in public areas or in groups is much safer. This path passes by prisoners from one of the biggest jails in the area, set to work in the fields near the school when they are three months from release.

Once she has passed these dangers, she eventually turns off and heads down a tree-lined road to her school. She must then make the journey again at the end of the school day to get home. “Even though I don’t enjoy the journey, and sometimes find it very scary, I am willing to do whatever it takes for me to get a good education,” she told the aid agency Plan International, which supports the school she attends.

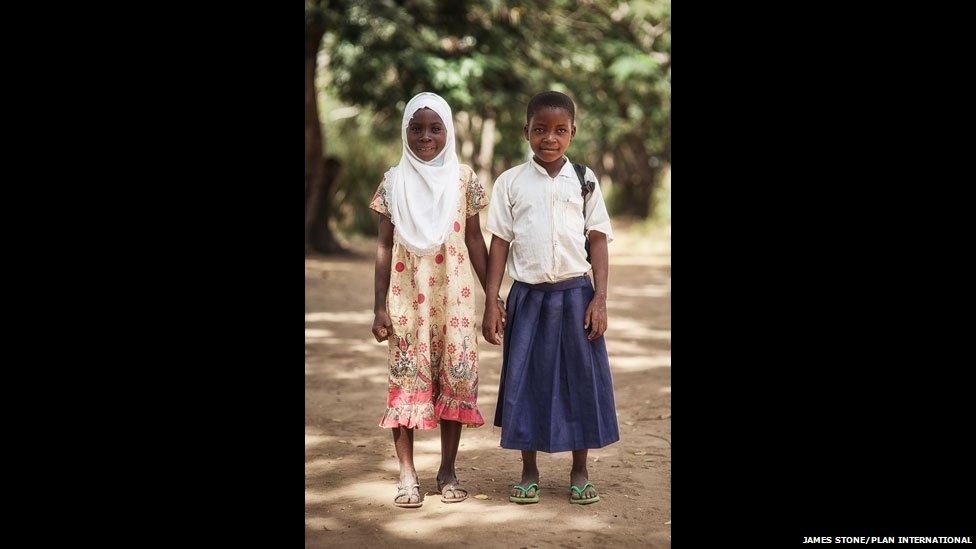

Sylvia sometimes walks to school with her 11-year-old friend Radhia - and this makes her feel safer. But this is only when her friend is not at school, as she attends a school around 7km in the opposite direction. Schools in Tanzania often have two shifts – morning and afternoon, or rotating days – so children sometimes go to school at different times or days. “We understand the need for a better education so that when we grow up, we will be able to support ourselves and our families and not face a life of poverty and hardship that we are currently used to,” Radhia says.

According to Unesco, the transition rate from primary to secondary education across sub-Saharan Africa is 62% for girls, but as low as 32% in Tanzania, where secondary schooling is not free. Plan provides assistance to help girls like Sylvia make the transition. In her village parents are hoping to one day build a primary school so that children will not have to make such long journeys to school – and they have just agreed to establish a day-care centre for nursery-aged pupils.

Her stepfather may view her as a financial burden for pursuing her education, but Sylvia feels it will benefit the whole family in the long term. “I want to be a teacher as I respect the people that teach me in school and believe that it will give me a better life than the one I currently have to look forward to," she says. (Gallery from Plan International and photographer James Stone. Both schoolgirls' names have been changed for their protection.)

- Published4 March 2011

- Published2 May 2023