The CCTV footage shows a white convertible in a narrow alley.

A man, dressed all in white, rushes towards the driver’s seat, stops for seconds, and then runs towards a motorbike driven by another man.

CCTV footage of Tara Fares's car, moments after the shooting

The white sports car slowly rolls down the alley.

Inside it is Tara Fares, Iraq’s most controversial social media star. She is dying from gunshot wounds.

It was 27 September, 2018. Ayoush had returned to her home city Baghdad after a short trip to Turkey.

About 15:00 that afternoon, Ayoush was called by someone on a mobile number she didn’t recognise.

“It’s me, Tara. How was your trip? Let’s catch up today,” the voice said.

Every detail of the call is seared into Ayoush’s memory.

Ayoush was one of the first well-known female DJs in Iraq. Steadily, she had built up a reputation, playing a mix of Western pop and local hits, but had branched out into promoting events.

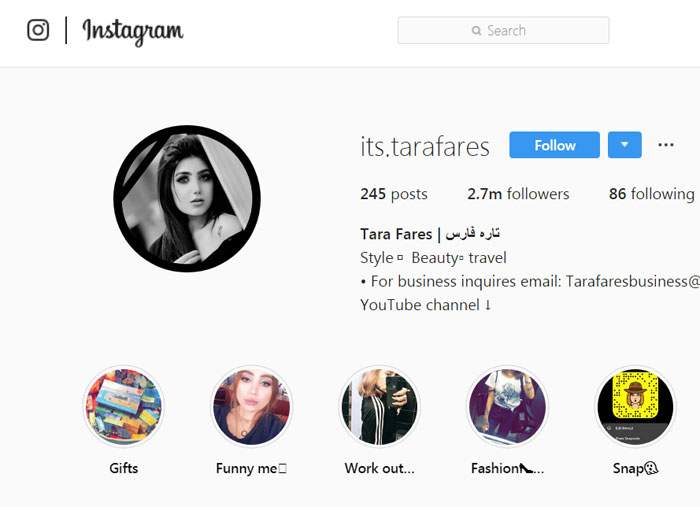

Tara Fares had a different kind of fame. Her 2.7m Instagram followers saw her in different outfits, showing off her tattoos or demonstrating make-up techniques. She posted about travel, books she had read and funny things that had happened.

Ayoush and Tara moved in the same circles - they were more than acquaintances, while being something less than close friends. But on this particular day they were to meet up in Baghdad’s al-Mansour neighbourhood, where the DJ’s office was located.

The women needed to discuss an event to promote a contact lens brand.

A couple of hours after the first phone call, Ayoush rang Tara to choose a meeting place. No-one answered.

She tried calling again at about 17:30. A young man answered, screaming:

“Tara Fares was shot.”

Ayoush immediately checked her Facebook account. There were already posts about Tara’s death. A number included a recent Instagram photo - Tara wearing a one-shoulder denim dress, posing against a pink background.

“I was scared. I went home immediately,” says Ayoush, 37, whose real name is Aisha Qusai. Her family had heard about Tara’s murder and were immediately scared that the DJ could be in danger.

Journalist Sary Hussam, 22, had interviewed Tara in April. He was also shocked. He was sitting with friends in a quiet café playing cards - as many young Iraqis do on Thursdays (when the weekend starts in Iraq).

The news spread like wildfire on social media. Everyone in the café suddenly knew. Sary couldn’t believe it and dialled Tara’s mobile number, but it went straight to voicemail -

Tara’s message was an excerpt of Eminem’s Walk on Water featuring Beyoncé.

Majd - not his real name - was one of the photographers who worked with Tara. It crossed his mind for a moment that it was all a publicity stunt - an outrageous attempt by Tara to get more attention.

It wasn’t.

By the time she was brought to the Sheikh Zayed hospital, just 4km (2.5 miles) from the crime scene, Tara was already dead, according to a nurse who was interviewed on TV.

Bullets had hit her in the head, neck and chest. The medics tried to resuscitate her but failed, according to al-Hurra TV.

Iraqi local media quoted official statements by the ministries of interior and health.

They confirmed it - Tara Fares, aged just 22, had been shot dead in the Camp Sarah neighbourhood.

The next day, the then Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, tweeted, saying he had ordered the security services to investigate and report back within 48 hours. He also promised to look into other killings.

Media reports suggested Tara was the third well-known young woman to be killed in Baghdad within two months. The timing of the three deaths was similar - all on a Thursday afternoon.

Rafif al-Yasiri worked at Baghdad’s Barbie Clinic offering plastic surgery not just to paying customers but also free to those who had suffered injuries. Rasha Hassan ran a beauty centre. Both were in their 30s. Both had died suddenly.

The grave of Rafif al-Yasiri at Najaf cemetery, Baghdad

The interior ministry had earlier said that Rafif took an overdose of drugs, while Rasha died of heart failure. But there were other conflicting reports about their deaths, and the lack of an official government verdict left room for theories and speculation, especially on social media.

“Rafif was a doctor, how would she take an overdose?” activist Mariam Mandalawi asked at the time. Many others questioned the authorities’ explanation for the deaths.

In the panic after Tara’s murder, her case and the August deaths of Rafif and Rasha were soon linked, despite a lack of evidence.

People started saying “liberal” women and social media influencers were being targeted.

News websites around the world rushed to cover Tara’s case and the possibility of a linked series of killings.

But there had been other killings - of male and female activists - that had been generating headlines in Iraq.

In late July in the southern city of Basra, lawyer Jabbar Karam al-Bahadli, who was known for defending protesters, had also been shot dead.

Two days before the killing of Tara, activist Suad al-Ali, 46, was shot dead in Basra. She had been taking part in protests in the city against the lack of basic services, drinking water and jobs.

Suad al-Ali

Tara’s killing was different - a well-planned shooting in the middle of the day in a safe neighbourhood in Baghdad, in a street monitored by CCTV.

“I was so scared when Suad was killed - I feared that other activists might face the same fate. But the government played it down,” says Faten Khalil Hattab, 25, an activist from Basra.

“After a few days Tara Fares was killed, it was the spark that scared women.

“Her death couldn’t be random, just as it couldn’t be random that Rafif, a beautician, was killed in Baghdad in ambiguous conditions, and it couldn’t be random that one week later another beautician was killed, also in ambiguous conditions.”

The prime minister had linked the deaths but official statements played down the idea of foul play.

The then Interior Minister Qasem al-Araji said Tara Fares “was killed by extremist groups, which are known to us. Efforts are being made to arrest them and expose them to the Iraqi people and get the just punishment”.

He suggested the case would be cleared up quickly.

In a TV interview on 11 October, the minister said that “accurate information” had proved that a “trained extremist group” killed Tara. He didn’t identify the group but said they had killed the aspiring Iraqi actor and model Karrar Noushi in the summer of 2017.

The model Karrar Noushi was alleged to have been murdered by extremists

He implied that the motorbike that carried Tara’s killer had been caught on CCTV.

In the aftermath of the killing one of those held was Ayoush herself. She was taken into custody in the women’s prison in Baghdad.

After an investigation, Ayoush was found innocent.

In the days after Tara died, those who knew her were afraid she had been killed because of her lifestyle.

Others who chose to live their lives differently said they had received threats.

Former beauty queen Shimaa Qasim told al-Arabiya TV she had been threatened on social media. Days after the murder, she did a tearful live stream from her home in Amman, Jordan. “I am not scared, but my soul is tired,” she said.

The wave of comments expressing happiness at the death of Tara had sickened her, she said, and she took a break from social media.

“How did the lives of people become so cheap? We are famous, but we are not whores, like some are saying.”

Shimaa Qasim

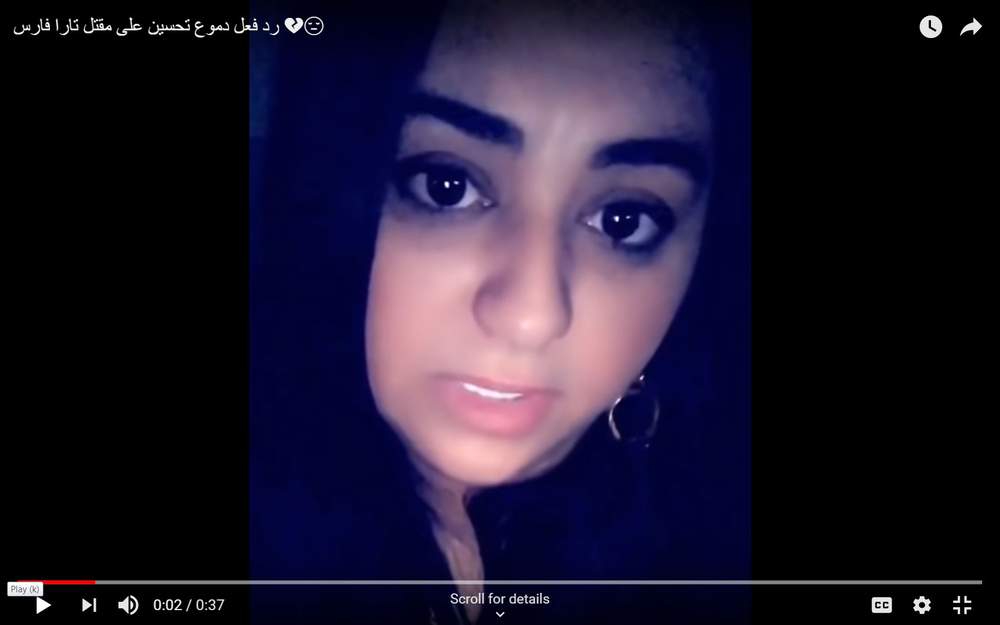

Another prominent woman, Dumooa Tahseen, 2018 winner of Iraq’s version of talent show The Voice, also expressed her anger and shock.

In a clip posted on social media, she said: “I have lost hope in this country. Is this the Iraq that everyone used to dream of?”

Dumooa Tahseen

Both women are from Tara’s generation - twentysomethings who had grown up in a time of violence. Tara was seven years old in 2003 when Baghdad fell to American and British troops.

“I still remember the sound of war,” Tara said in a YouTube interview months before her death. Sectarian violence cost the lives of many thousands of civilians.

The role of women then was “passive”, says Loubna (not her real name), a young lecturer in Baghdad.

“Women were trying just to avoid the ongoing violence and survive with those who remained from their families. They lost husbands and children. They also had to move and leave their own houses behind.”

“Baghdad’s streets were destroyed. They looked dim and lifeless,” says journalist Sary Hussam.

2003: Air attacks on Baghdad

He first met Tara in 2014 during a “Miss and Mr Elegance” competition in Baghdad – a kind of fashion and beauty pageant. Both were volunteers with NGOs.

Tara was then 18, but had already been through a lot - dropped out of school, separated from her husband and been left as a mother without a son.

“She was introverted and less confident,” Sary says.

And yet she became someone different, someone who was not too scared to live.

(Above: Sary Hussam)

That same year, 2014, saw the Islamic State group declare its “caliphate”. They were soon notorious for their brutality - beheading enemies and ruthlessly enforcing Sharia law.

Even away from areas controlled by IS fighters, some women worried about their right to express themselves, to live their lives as they wanted.

Loubna left her city, Baghdad, because she felt unable to do the things she loved, including the simplest things like wearing clothes she liked. She returned four years later, just a month before Tara’s death.

Tara herself decided to live in Irbil, in Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region, which was seen as safer than Baghdad. But she continued to take risks, and there was a constant stream of criticism.

Tara was called a prostitute. Those who worked with her were told they were “bringing shame” on themselves. But she carried on regardless.

Both before and after Tara’s death, threatening messages were sent to a number of women, mainly to artists and activists.

Some of the messages warned: “You’re next, next Thursday.”

Fear filled many hearts. Some families even pushed their daughters, and sometimes sons, to leave the country - at least temporarily.

Others remained, but stopped their activism and disappeared from social media.

Faten Khalil describes herself as a feminist activist, and became well-known in Iraq after doing a TV interview about child marriage.

Faten decided to leave Iraq shortly after Tara’s death and is now seeking asylum in Turkey. She says she received death threats on her Instagram account, saying: “You’ll be next.”

Faten Khalil

Another woman, who does not want to reveal either her name or her field of art, also fled. Some time before Tara’s death she received a threatening note and decided to leave and deactivate all her social media accounts.

She had been getting hostile comments, such as: “What you are doing is haram [prohibited in Islam].” Her parents felt she should leave town until things were calmer.

“Baghdad is tiring, annoying and harmful, but I love it. I don’t know how to explain it,” she says.

Hanaa Edwar, an Iraqi activist in her 70s, believes that with the defeat of IS in Iraq in the summer of 2017, something changed. The country was regaining its normality, and women became more visible.

But some groups, which she did not identify, were not pleased with this. They wanted women to withdraw from public life.

“I will never forget the fireworks that coloured again the sky over many cities across Iraq on New Year’s Eve. Men, women and children filled the streets. People became again optimistic,” she remembers.

She points to the increase in the number of women who participated in the parliamentary elections in May 2018 - the first one after the fall of IS. This was despite harassment and abuse from men angry at the cheerful, confident faces of women appearing on posters.

Hanaa Edwar

Video of sexual content said to be of female candidates were leaked in an attempt to scare them and push them away from the public arena, Hanaa says. In the end, though, more than a quarter of those in Iraq’s parliament were women - a proportion that is higher than in the US.

“Women have taken part in everything from anti-corruption protests to the opening of galleries,” says Hanaa.

But “society is not ready yet to accept this,” Loubna, the lecturer, says.

When Loubna returned to Baghdad, she also noticed that life had changed - women were more visible in public spaces.

“The NGOs played a big role in bringing women back to the public spaces. Women have reclaimed their place through their work,” Loubna said.

Women’s clothes are a good reflection of how things are. In al-Mansour, a central neighbourhood of Baghdad, Loubna wears a T-shirt with jeans. In al-Sadr city, she wears a long shirt, wide trousers, and an Abaya - a loose, flowing, outer garment.

In Kurdistan’s al-Sulaimania she feels as she does in Istanbul, where she says no-one notices women’s attire.

“What has happened recently shows that the women are playing a role bigger than the one tolerated by the society,” Loubna says. “They fear women.”

Six months after her death, Tara’s killers have not been brought to justice.

Her case, which was on the front pages in Iraq at the time, now seems largely forgotten.

Even for those most affected by her death, life goes on. It always has, through all the tribulations which the country has endured.

As Sary puts it: “We Iraqis have overcome horrible incidents. We learned to keep thinking only of the future.”

(Above: A mourner at the grave of Tara Fares)

Iraq has no shortage of unsolved murders. There were many different theories for why Tara Fares was murdered and who might have done it.

Hanaa Edwar says two young men said to be close to Tara were charged with her murder but released by a judge in February because of a lack of evidence. It has not been possible to confirm this.

“Just like most crimes here in Iraq, this case will be closed and the perpetrator will never be identified,” she says. “I am deeply sad and angry at this rampant insecurity.”

The case is complicated, says Hussein Allawi, a lecturer on national security at Baghdad’s al-Nahrain University. He says the timing of the killing might explain why it hasn’t been solved.

“She was killed in a transitional period when the government was about to change.”

A month after Tara was killed, the Iraqi parliament ratified the assignment of new ministers - but the ministries of interior, defence and justice remained vacant.

Even now Adel Abdul Mahdi, the prime minister, also acts as interior minister. He has announced: “We will work on restricting weapons to be only in the hands of the state. We will work on putting an end to the security chaos.”

Since Tara was killed, only one person was allowed to speak on behalf of the authorities - Maj Gen Saad Maan - and he will not comment on the case.

“We are used to the security authorities not revealing the [results] of ongoing investigations,” says Allawi. There are only two options, he says: “The killer has either not been identified, or the name is not announced to the public yet.”

Hanaa Edwar says some kind of pressure is exercised over the interior ministry. “Horrible secrets lie behind these killings.” She refers to the killers as “ghosts”.

Efforts are being made to improve the security situation, but targeted killings of both men and women continue.

2018: Iraqi federal police on patrol in Baghdad

After Tara’s death, on 12 October, a teenage boy was killed because he was suspected of being gay. On 2 February 2019, four months after the killing of Tara, the Iraqi novelist, Alaa Mashzoub, 51, was shot dead by an unknown assailant in Karbala, in southern Baghdad.

But the lack of security doesn’t stop people carrying on with their lives.

Loubna, the young lecturer, says: “Beauty centres are open as usual, life is normal, people go to malls and party.”

She says she noticed that “the cultural landscape has revitalised in Baghdad”. She is now participating in some social forums and feminist clubs.

A mall in Baghdad

But the path of some people has completely changed.

“Although I never met her or followed her, Tara has changed my life in one way or another,” says Faten.

“She shared a clip of a TV interview I did on her social media pages and commented ‘Bless her’. Also, once I wrote defending her when people were bullying her.”

Faten is still waiting to hear about her asylum application in Turkey. She is now running a small online boutique, where she buys Turkish clothes and sells them to Iraqis, until she can find a job.

Life has not been easy, but Faten doesn’t regret leaving Iraq.

“I felt that the state is unable to protect its citizens. Only the elite and high-profile are protected. We, the ordinary people, are remembered just for votes.

“I can express my opinions freely from here,” she says. “There, I had to think of every single word I said. I was threatened despite the fact that I never criticised any political or religious group.

“I don’t want be killed in Iraq, I don’t want people to write bad comments about me.

“We were not born and raised in a healthy environment. We have seen killings, explosions, ISIS beheading people, and displacement.

“Baghdad is like a ticking time-bomb. It can appear calm and normal, but then something big happens. We are used to it.”