As we drove into the market in al-Dora in southern Baghdad the driver announced: “Welcome to the swamp.”

The place reeked of violence. It was April 2007 and the Americans, after years of unsuccessfully fighting the insurgency sparked by their invasion of Iraq, were striving one last time for some sort of victory.

Tens of thousands of extra troops were going in - the Surge.

Back in 2007, death stalked the streets of al-Dora. One reporter dubbed it “the most dangerous place in Iraq”.

When we arrived early one evening the place was deserted. The few market traders still there opened for just a couple of hours each morning.

For the rest of the day and night local inhabitants cowered in their homes while the militant Sunni opposition tried to kill both Americans and other Iraqis.

Shia death squads, meanwhile, targeted the Sunnis that made up most of the local population, aiming to force them out.

In autumn 2006, the Islamic State - in its first incarnation - had been declared by al-Qaeda in the west of the country. Pounded by the Americans there, some fighters had escaped to al-Dora, where they seized a foothold in the capital of Iraq.

Before the invasion of 2003 the suburb had been a place of market gardens, vegetable sellers, and restaurants.

Streets of low-rise family homes were laid out in a grid pattern, and the almost bucolic nature of the suburb made it popular with middle-class families. The houses had little enclosed gardens and the area was sprinkled with date palms.

The parallel thoroughfares were numbered rather than named and groups of them formed city blocks.

The market is to the north of these residential blocks, and marks the transition to urban Baghdad proper.

Al-Dora’s semi-rural location on the southern fringes of the capital made for good quality of life before the invasion. But afterwards it made it easier for insurgents to infiltrate from the desert hinterland, and by early 2007 they were destroying its tranquility.

The place became a free-fire zone. Al-Qaeda shooters picked off passers-by, death squads cruised, and bomb-makers planted IEDs (improvised explosive devices) for passing Humvees.

We were on a media “embed” with 2nd Platoon, a unit of 40 men that was part of A or Gator Company of 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment (referred to in US Army-speak as 2-12 Infantry).

While we were staying in the al-Dora outpost a woman out foraging for her family was brought in shot. A middle-aged man took a round too, and a younger fellow was hit while trying to make his way from door to door dodging the snipers. It happened every day.

Medics swept fist-sized bullet wounds with Quikclot (a clotting agent that shut down bleeding with amazing speed), patched up these random Iraqi victims and drove them to the US combat surgical hospital in the Green Zone.

“I wouldn’t stand there, dude,” one of the soldiers told me during my first morning out in the market. “There’s a sniper works this street.”

During our short stay a rocket-propelled grenade was fired into the outpost and a Humvee hit by an IED only 50m from its entrance.

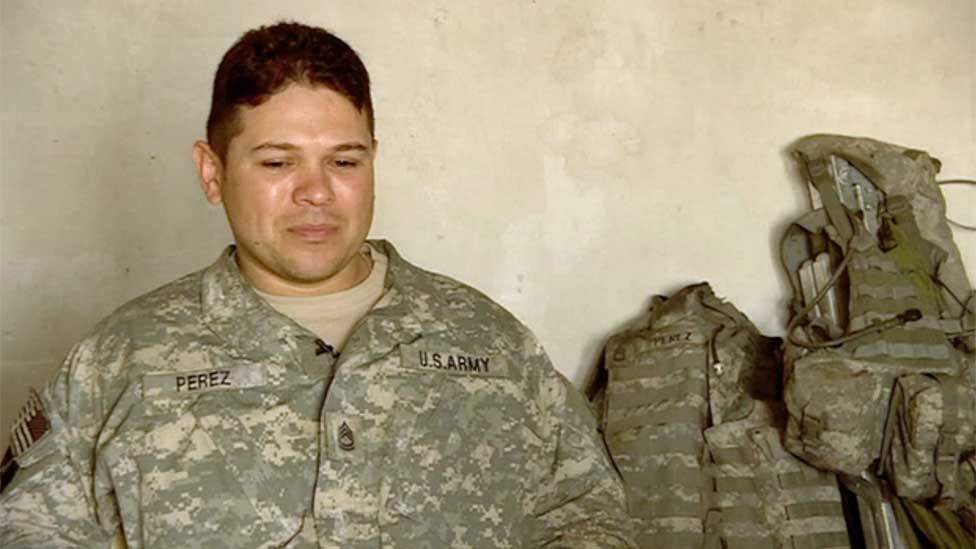

After arriving with 2nd Platoon, we quickly got to know its commander, as well as Platoon Sergeant Dorian Perez.

Sitting drinking tea with them in an abandoned food shop within the outpost, they spoke with complete frankness about the daunting task they were facing.

Just a fortnight or so before a huge bomb under the street had destroyed one of their “gun trucks”, killing two of the platoon’s soldiers. A similar blast had also killed a man from 1st Platoon. Three men dead in as many weeks.

The combat infantryman or “grunt” is the basic building block of military action.

But this indispensable ingredient in war is also, historically, the type of soldier hardest hit by the experience. They are the most difficult to integrate back into civilian society when it’s over.

The soldiers we interviewed had other options but had chosen the infantry. They wanted to fight.

Dorian Perez, a native of San Antonio, Texas, had actually been trained as a satellite communications technician when he joined up in 1992. That job could have given him an easy life in the army and a highly paid civilian occupation when he left. But in 1997 he chose to become an infantryman, in part it seems because he thought his father, a multi-tour Vietnam War veteran, would not ultimately respect him unless he did.

Dorian Perez in 2007

Dorian tried to live by his own warrior code, inspired by three key texts: Robert Heinlein’s sci-fi novel Starship Troopers, Steven Pressfield’s Gates of Fire, a historical fiction about the battle of Thermopylae, and a modern translation of the samurai code or Bushido.

Compared with other soldiers I met in Iraq, Dorian was unusual in the thought he had given to the business at hand.

For many of the younger soldiers, the graphic TV images of the falling Twin Towers in New York, taken down by jihadist hijackers on 9/11, played a key role in their decision to fight.

Nick Mazzarella, 2007

Nick Mazzarella, working for a Florida roofing contractor, talks about “9/11 fever”, motivating him. “I was young, naive and I wanted a little bit of vengeance.”

He wanted education too, knowing that if he served in the army he could get government funding for college when he got out.

Cody Edmondson, a native of Miami, Oklahoma, already had a degree in construction and was working in that field in Texas when 9/11 happened. A couple of years later he lost his job.

Cody Edmondson, 2007

The Army recruiter asked him, “why are you here?” when he opted to join as an infantryman, since his degree could have got him into officer school. But Cody “wanted to start at the bottom and work my way up”. He didn’t want to be giving orders unless he’d already proved he could execute them.

Benjamin Jones also encountered a little scepticism at the recruiting office. Seeing his scores in the aptitude tests, the recruiter couldn’t understand why he wanted to be a grunt when he could be almost anything.

Benjamin Jones in 2007

“I said I want to do stuff that they do on the recruiting videos,” Benjamin recalls, sitting in his home in Adams County, Pennsylvania, just a few miles from where he was raised, and where he signed up in 2003. For him, it was about leaping out of helicopters and closing with the enemy.

All four men got more action than they bargained for.

In all the unit served 15 months in Iraq - an extraordinarily long tour even by the standards of the US Army at the time, which generally set a one-year maximum.

The unit would do a six-day stretch in the al-Dora market, followed by one day off back at a nearby base, and then back to the streets. Their enemy used hit and run tactics - concealed bombs, sniping, or mortars. So 2nd Platoon seldom saw their foe, but lived for many months under constant risk, with all the strain that that involved.

Nick, who survived an IED blast that killed another man in his vehicle on his first patrol in al-Dora, and then had a further two near misses, was convinced he wouldn’t make it out alive.

The third of those incidents happened just yards from the combat outpost, as we were filming there. Dusted by the blast, he was rushed into the sick bay for a check up, declaring himself “stoked” as he grinned into our camera. But that momentary relief at his survival hid an inner dread, that Nick reveals now. “After a while I thought, you can just write me off.”

Cody agrees - they felt they were headed for oblivion. “It was just kind of easier not to worry about it.”

The return of the brigade that 2nd Platoon were part of to Colorado was to become a defining moment. It went on to change the US Army’s attitude to mental health and managing the return of battle-weary troops.

In late 2007 and 2008 there were a string of murders in Fort Carson by soldiers who had returned from Iraq. There were also a large number of incidents involving drink, drugs, and attempted self-harm.

Did we, as leaders, understand the impact of rapid deployments?I know that I personally didn’t

An army study was published in 2012 in the journal Military Medicine. It noted “a possible association between increasing levels of combat exposure and risk for negative behavioural outcomes”. In layman’s terms, they had been asked to put up with too much for too long.

“Did we, as leaders, understand the impact of rapid deployments?” asks Duane France, an officer who served on that ill-fated Baghdad tour and later left the army to establish a mental health practice near the base in Colorado. “I know that I personally didn’t.”

Key to the problems was the amount of time the troops spent in combat. During the years 2004-2009, 2-12 Infantry spent not much more than two years at home, creating a battle-stress time bomb. “The military was deploying at unprecedented rates unseen in modern military history,” comments France.

“My original position was PTSD: you know it's not real,” Dorian Perez says, as he sits in a Virginia hotel.

He’d always felt it was a scam. “This is something that people are using to try to get some money from the VA [Veterans Administration].”

But as he carried on his duties at a training base in Louisiana he was bewildered when the sound of a firecracker used on an exercise caused him to dissolve in floods of tears.

After he’d left the army in 2012, and been to college in North Carolina to study agriculture, he started noticing other symptoms. He couldn’t sleep unless he had a loaded pistol under his pillow. “My comfort,” he calls it.

If Dorian woke, sometimes after just a couple of hours’ sleep, that would be it for the night. By the time he’d graduated he had taken to hiding guns in different places in his apartment, just in case. They were needed, he says, for him to hold on to - “my sense of safety”.

For Dorian, on the verge of his forties as he headed into civilian life, it was seeing the symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in another soldier, that finally made it feel OK to talk about it.

He calls this friend “the hardest man I know, the warrior’s warrior”. For six years after coming home, this man had slept in a different bed to his wife in fear that he might strangle her in his sleep.

Like many soldiers returning from Iraq, the 2nd Platoon men had been damaged in various ways.

The IEDs or roadside bombs that became such a feature of life during patrols in al-Dora caused enormous physical effects, as well as psychological trauma.

Nick was diagnosed as suffering from TBIs or traumatic brain injuries from his brushes with death. This affected his memory, and his mother suggests that there’s much of his childhood that now seems to be lost.

Cody also talks about memory problems - something he associates with the medication he was on as well as his time in combat. For Benjamin Jones, a heart problem resulted in a medical discharge from the army. Proximity to IEDs was the trigger, the army doctors thought,

All four of the men - Dorian, Cody, Nick and Benjamin - have suffered from the effects of PTSD.

Millions have served in America’s recent campaigns, providing mental health workers and academics alike with work for the foreseeable future. It is all part of the legacy of wars of choice, and the relationship, often uneasy, between a society and those it sends to fight.

All of the soldiers speak with some care on this topic, for fear of re-opening old wounds. Looking back on it, Dorian realises he had just been too fixated with getting through the tour to understand what was going on at home. “She realised that she no longer had those feelings for me, and I remember that put me into a bad spot.” He’s still single, and jokingly compares dating to, “looking for an IED”.

You will search in vain for definitive statistics about the fate of US military marriages but some surveys exist. One suggested that non-commissioned officers in the military had the highest divorce rate of any occupation, with 30% of marriages ending by the time they reach 30. Another found that long deployments significantly boosted the chance of breakup.

For soldiers coming home, there are questions about opening up to spouses, other family members and friends. And this hints at a deep division between those who served, often in extreme jeopardy, and the vast majority of the population.

Although they have all been on the rack - with PTSD, lost relationships, and alcohol - two of them told me that they have seriously considered going back into harm’s way as security contractors.

Both Dorian and Cody still shoot military specification semi-automatic rifles regularly - for fun - and both, it seems, miss the camaraderie and sense of purpose that comes with being on operations.

Benjamin Jones, another proud gun owner, has taken the route followed by many veterans, of working in law enforcement. “When you’re infantry, that’s kind of an obvious way to go,” he notes. Soldiers who learned trades have different prospects of course. For Nick being a cop was not an option. The last thing he wanted after al-Dora and Afghanistan, “was to get shot at some more”.

The story of the returning soldier is one that echoes throughout human history, chronicled by everyone from Homer, to Shakespeare, and Kipling. The soldiers have always suspected that those who lived comfortably at home don’t understand them.

I still feel awkward when people thank me for my service because the first thing that comes to mind is, ‘I didn't really do it for you’

One rainy morning we went with Dorian Perez to the Vietnam war memorial in Washington DC. He compared their situation favourably with his father’s. America was so polarised by Vietnam that they had come home, “to be spat at, have dog waste thrown at them”. It’s very different today, he feels. But still there is a divide between the warriors and the society they served.

Travelling around doing our interviews, you notice that serving members of the military get to board the flight first at US airports. There are posters and memorials commemorating the fallen, and one often hears the words, “thank you for your service”. It’s laudable of course, but many veterans are not entirely comfortable with it.

“I still feel awkward when people thank me for my service because the first thing that comes to mind is, ‘I didn't really do it for you’,” Nick explains, “I wasn't thinking about protecting our freedom or our rights or anything like that, I was just thinking that I wanted to blow some shit up!”

With all volunteer armed forces the bond between the fighters and the wider society they serve is often slender. But while veterans like those of 2nd Platoon are still intensely loyal to one another, and defined by their experience, there are some paths back to integration, and there is something society can learn from their experience.

Back in late 2007, Nick Mazzarella was quite direct in response to that question. No, it wasn’t worth even one of the guys they’d lost. Now he’s had more than a decade to reflect, his answer is a little different. “I feel like we accomplished our objective,” he says, “but I'm always going to be bitter about the lives that we've we sacrificed to accomplish that goal.”

Swiftly, he moves to the wider meaning of what they did, and the moral for America. “I hope that we've learned our lesson.” And on this point we found consensus among our veterans. From Trump supporter Cody to disillusioned Obama voter Dorian, they do not believe America should act as the world’s policeman.

“Why should we take care of everyone else?” Cody asks, as he sits in a family farm founded during Oklahoma’s dustbowl of the 1930s, “I mean it's time to put Americans first.”

Re-married, he now has two young daughters, and for Cody, as for Benjamin, family is now the pathway into the future. Nick’s kids are a little older and he is also a devoted father. He works in a psychiatric unit now, and hopes to further his professional education so he can help fellow veterans in crisis.

For Cody, meeting Miranda, his second wife, turned his life around. Her message to him was: “Look man you need to get your act together. Let's do this! …I mean she kicked my butt into gear.”

Dorian Perez is single and the only one of the four without children, charting his future instead through new adventures. He’s moving to Alaska - “the last frontier” as he calls it - continuing his work for the Department of Agriculture, conserving the soil and trying to foster good farming practice.

Now in his mid-forties, Dorian doesn’t do anything by halves, the former warrior is truly committed to his new work, and talks about going to the developing world, Haiti for example. But there is a part of him that cannot escape Iraq, and specifically what they left behind in al-Dora.

He yearns to know what it looks like now, and how the Iraqi kids they met on patrols are doing. “The kindergarten that we built, is it still there? Did they ever finish the primary school?”

Benjamin too voices the hope that the people in al-Dora will remember them as something other than the “Great Satan”. “Maybe they'll be like, ‘oh no these guys helped us they were good guys’.”

Having been back to al-Dora in 2014 and filmed with local people, I can answer some of these questions. The kindergarten is indeed thriving. Although there have been sectarian tensions, for example with the re-emergence of Islamic State, it remains a far more prosperous and stable place than the killing ground we experienced in 2007.

Did that justify the death and destruction? However well they manage in the future, working hard, trying to be good members of society, fathers and husbands, ultimately those are questions that the survivors of the 2nd Platoon will never escape.

FIND OUT MORE

National Center for PTSD - US

Mind

PTSD - NHS

CREDITS

Writer: Mark Urban

Producer: Maria Polachowska

Photography: Mark McCauley

Additional photos: Getty Images

Online production: Ben Milne

Editor: Finlo Rohrer

Publication date: 26 October 2018

Built with Shorthand

All images subject to copyright