Interview with Barny Revill, Series Director

Interview with Barny Revill, Series Director of Earth From Space.

It’s only really from space that you can see how tiny, fragile and unique this planet is, and also how everything is connected.

Can you tell us a bit more about what viewers can expect, and how this series is different to other natural history series on the BBC?

With this series the viewer is given a unique perspective on our planet. From space you can see things that previous natural history series couldn’t show you. Whilst in other programmes you are generally looking at animals and behaviours in isolation, in this series with cameras able to look down from far above, you see the context of how these stories fit into the wider world.

It’s only really from space that you can see how tiny, fragile and unique this planet is, and also how everything is connected. You really get a sense of how, like the butterfly effect, something happening in one place can have an impact thousands of miles away.

As well as a deeper understanding of our world, this new perspective also gives us some really interesting ways of looking at what’s happening. We can see things that our animals can’t - be it something coming along to rescue it, like much needed rain after a drought, or imminent threats approaching, like hurricanes or deforestation. We can see how the environment can dictate the behaviour of an animal, and indeed how an animal can shape the landscape around it. And of course with the satellite archives and the ability to take repeated images of the same location, we can look at the changes over time.

What I love about this is that it gives you the complete story like never before. The challenge I suppose was to combine the intimate details of these single animal stories with the vast perspective from space, making it work seamlessly so it didn’t feel like two different shows. I hope we’ve managed to do that.

How did you decide what stories to feature and what satellite images to use?

There are some spectacular images and some glorious views that you can get from space, but we didn’t just want a pretty picture or an introduction to a location from a satellite image. We wanted to find stories where the view from space was integral. For instance, it could be something strange or unusual that we could see from space - whether it was an incredible shape, a movement or a pattern.

Then we would reveal the story behind it - what lies at the heart of this intriguing image and how it affects the animals on the ground. Or the other way around, engaging with a story or character, but then through the perspective from space, realising that the animals were influencing the planet, creating a certain shape, pattern or change visible from space.

In essence, we were always looking for stories that were intimate, beautiful and character-led which would also give us the bigger picture, and the view from space would help us understand both their and our place within the world.

Was it challenging to combine satellite images with footage filmed on the ground and in the air to create seamless zooms down from space?

High resolution commercial satellite technology is at the stage where each pixel in an image represents 30cm on the ground. This means you can see buildings, cars and trees in your garden. So from the very beginning we had this idea of tracking an elephant from space. It’s an animal we thought would be big enough to see but they also had a bigger story to tell. So how hard could it be to get a satellite image of an elephant from space, while simultaneously filming it on the ground?

I was on the ground in Buffalo Springs National Reserve in Kenya, having identified a lovely family of elephants to film with the help of a charity which has GPS trackers fitted on several of the herds. But I needed to predict where they would be 48 hours in advance, as that was how long it would take to get the GPS coordinates through the imaging company, up to the satellite itself and then on its next orbit around the world where it was passing over Kenya, to take the image.

High resolution images are usually about 10km by 10km, so they cover a relatively small area, and an elephant can move a lot further than that in a day. And even if I got the location right, one little puffy white cloud could ruin everything. On the day in question, at the precise minute the satellite was passing, there were clouds around, but we had a drone in the air and cameras on the ground filming. And a couple of days later we were sent the images from the satellite and we realised we had our elephants in shot and they matched our footage, meaning we could seamlessly transition from one camera to another.

Do you think satellite images can help us understand our planet better?

Satellite images have a huge potential to explain the world and there is a whole new perspective to be gained once you start seeing it from space. One of the most exciting things for me is some of the discoveries that people have made thanks to satellite imaging.

Antarctica is a pretty tough place to explore to make new discoveries. Scientists have now realised that they can scan huge areas very quickly and isolate possible areas of interest to investigate from space. In the series we see how emperor penguins huddle together and they eat the snow beneath their feet to drink. But a whole colony of penguins produces a lot of poo and, as it shuffles across the ice to find fresh snow to drink, the colony leaves a brown patch behind. Because the patch is much bigger than the colony and more distinctive that the penguins themselves, 26 new colonies of emperor penguins have been discovered just by looking from space, doubling the known global population.

When you look at Earth from space you also realise that the tiny slither of blue around the planet is our atmosphere and we’re on this fragile little globe, where everything we do inevitably has the potential to have a huge impact. Astronauts talk about the 'overview effect' and to some degree this series gives the audience that. It is a very powerful way to look at the natural world, and hopefully this series will inspire people to love our planet and help conserve it even more.

What moments are you most excited for people to see?

For me one of the most stunning moments from the series is the kung fu performance. It’s one of those things you hope will look good but to see all those kids performing in unison, creating shapes that are visible from space, it’s quite a humbling experience.

I also loved some of the smaller stories within the series like the Siberian squirrel, a fluffy white squirrel with big beautiful eyes found in Japan. What was a real surprise to me is that Japan is one of the snowiest places on Earth and these squirrels have a unique way of dealing with it. Normally they are nocturnal and solitary creatures but when it gets really cold and snowy they change their behaviour. They start to come out more in the daytime and when they go to sleep they quite often huddle up together. So you have these super cute fluffy squirrels snuggling up for warmth in these cold nights. Adorable.

What was your most memorable moment whilst filming?

On the Gulf Coast of the United States, where we found ourselves filming in the days leading up to hurricane Harvey. We were filming a little beach mouse which is very susceptible to hurricanes because of the exposed dunes it lives on. We thought it would just be a story that was only theoretically about hurricanes, and then suddenly we found ourselves with hurricane Harvey on its way.

Being involved in these moments that become part of history is what it’s all about. And of course satellite images before and after the hurricane and showing the flooding and destruction around Huston were devastatingly powerful, as well as being used in the rescue efforts.

This, like other stories featured in the series, is a powerful reminder of our changing climate and changing world. We are telling stories that really matter in an engaging way, and I suppose being able to do this makes what we do really special.

The time lapses featured in the series are mesmerising as they capture a perspective that otherwise would be hard to appreciate. How did you put these images together?

The beauty of satellite images is that you can overlay images of the same place over time to see how it’s changed overtime. We did this by commissioning multiple images of a location to see the change across a year. But there is also an incredible archive of satellite images available, and with them (and a lot of very hard work!) we could put together time-lapses that showed change across years or even decades.

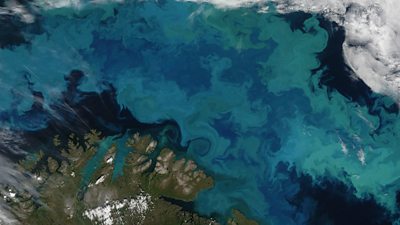

Pictured: Phytoplankton bloom in the cool waters of the Barents Sea off the coast of Norway and Russia. Image Credit: NASA