The Norman Conquest 1066

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions

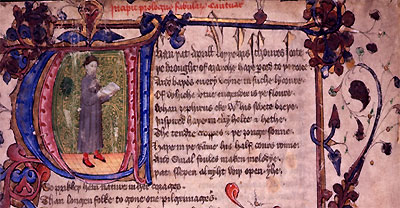

- Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

- When April with its sweet showers

- The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

- has pierced the drought of March to the root,

- And bathed every veyne in swich licour

- and bathed every vein in such liquid

- Of which vertu engendred is the flour

- from which strength the flower is engendered;

- Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

- when Zephirus also with his sweet breath

- Inspired hath in euery holt and heeth

- has breathed upon, in every woodland and heath,

- The tendre croppes and the yonge sonne

- the tender shoots, and the young sun

- Hath in the Ram his half cours yronne

- has run his half-course in the ram,

- And smale fowules maken melodye

- and small birds make melody

- That slepen al the nyght with open eye

- that sleep all night with eyes open

- So priketh hem nature in hir corages

- (so nature rouses them in their hearts)

- Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages.

- then people long to go on pilgrimages.

- The Norman Conquest 1066

- In 1066, William of Normandy invades England, ushering in a new social and linguistic era. But the change at the top takes a while to sink in, and manuscripts continue to be written in Old English as late as 1100.

French is rapidly established as the language of power and officialdom. William appoints French-speaking supporters to all the key positions of power, and this elite of barons, abbots and bishops retains close ties with its native Normandy.

But English is far too entrenched and continues to be used by the majority of people. With Latin the language of the church and of education, England becomes a truly trilingual country.

- Language development

- English continues to evolve after the Norman Conquest, particularly in grammar. Word order becomes increasingly important in conveying the meaning of a sentence, rather than the traditional use of special word endings.

Clever new constructions enter the language, such as the auxiliary verbs 'had' and 'shall' (had made, shall go).

Spelling and pronunciation begin to shift too, as Norman scribes spell words using their own conventions, such as qu- instead of cw-. Slowly but surely, distinctive Old English characters begin to die out.