Red ribbons and Olympic prizes

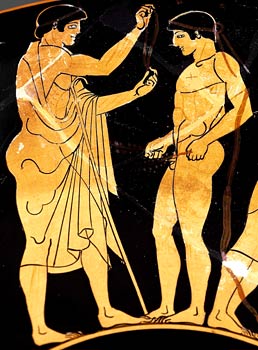

Many ancient Greek pots show athletes wearing red ribbons, not just tied around their head, but sometimes also on their arms and their legs. Such ribbons can be seen on this Athenian kylix, or drinking cup, of about 500-475 BC, now housed in the British Museum. These ribbons (or more accurately skeins of wool), along with palm or other branches, seem to have been given to the winners immediately after their contests. Later, at the prize-giving ceremony, they would receive the rewards customary for those particular games (each festival had its own particular prizes).

At the ancient Olympics, the only prize was the crown of olive leaves cut from the sacred tree at Olympia. What counted most of all was the fame and supreme glory of becoming an Olympic victor, embodying the concept of arête, or excellence. There were no medals. Only the winner's name was recorded, since coming second or third counted for nothing.

At Olympia, the olympionikes, or victor, was allowed to set up a statue of himself to commemorate his success. This would be a standard statue in the case of one win, or for three wins he could commission a portrait statue of himself from a leading sculptor such as Pheidias or Myron. Victory songs would also be specially written for him, the most famous today being those by Pindar.

These privileges somehow had to be financed. Statues of bronze or marble could cost up to ten years' wages for the average worker, and sometimes the state would sponsor an athlete, paying for his training and perhaps a victory statue. This was a worthwhile investment, as sporting victory was very prestigious for the home state.

The successful athlete would also sometimes be given privileges such as free board and lodging, and theatre tickets for life. Olympic victors in particular became heroes, and had huge followings of fans. By competing in the many other athletics festivals where material prizes were given, they could earn a very good living.