When the Great Western Railway ran its first train in 1838 the Directors of the Company had little idea of the developments that lay in the future. The great railway boom had only just begun and nobody really had any idea of where it might lead.

Obviously, the Directors and supporters of the Great Western hoped their line would survive and flourish – and, of course, make them a lot of money - but even they would have been amazed to see the railway still operating in the twenty-first century.

The Chief Engineer of the GWR, Isambard Kingdom Brunel – a man now regarded as one of the supreme inventors, designers and engineers of the Victorian period - was convinced that the future of rail travel lay with broad gauge. He built his railway on lines that were seven feet wide, providing incredibly safe and comfortable travel for passengers.

However, not everyone thought the same, and Brunel was proved wrong. With other railway companies using the standard gauge of four foot eight and a half inches, changing from one gauge to another was just too inconvenient. The last Broad Gauge service ran in 1892 and railway tracks have been standardised ever since.

Like them or hate them, railway companies – both in the time of private enterprise and the nationalised British Rail - have been developing and improving the engines and the carriages, the rail tracks and the infrastructure around stations and goods yards, since the days of Brunel.

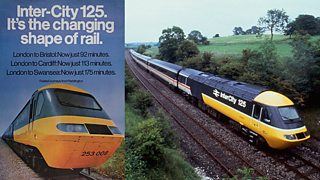

The introduction of the revolutionary Inter-City 125 train fleet in 1976 is just one example of this development.

In the years following the end of the Second World War, it was clear that the newly nationalised British Rail had serious problems. Lines and locomotives needed to be upgraded and the advent of the motorway system was providing a serious threat to the freight service.

In a virtually bankrupt Britain, the government was unwilling to fund new railways – which would have been the ideal solution - and so the British Transport Commission switched its attention to the rolling stock and to the vehicles that ran on the lines. They would also, it was decided, provide new engines with increased speeds. The Inter-City 125 was born.

BR poster and Inter-City125. Images: Science & Society Picture Library/SSPL/Getty Images

The name Inter-City had been used in 1950, on the London to Wolverhampton route, but it was the autumn of 1976 before the new trains were introduced on the old Great Western line from London to Cardiff. The first 125 train rolled into Bristol on 4 October that year, three minutes early, before moving on to south Wales.

The name 125 came from the fleet of diesel locomotives that operated at speeds of up to 125 miles per hour. They were, however, capable of making 148 mph as an absolute - but not necessarily desirable - top speed. The railway lines were simply not made to take such pace and motion and so 125 it was. As a marketing slogan Inter-City 148 would, in any case, not have sounded as good as 125.

In its day, those amazing speeds made the Inter-City 125 locomotives the fastest diesel-powered trains in the world.

As well as the locomotives, the coaches and carriages were also state-of-the-art. Finances dictated that they were not all brand new but, even so, new lighting and improved seating added to the comfort of passengers.

Soon the Inter-City 125 services with their distinctive blue livery (with a grey surround for the windows and doors) were a familiar sight on all railway lines and at stations across the country. Television advertising trumpeted the quality and performance of the Inter-City 125 trains – “Inter-City, big blue train, away from it all, then home again” as one advert ran.

Three decades on, most of the high-speed trains are still in operation although the brand name, Inter-City 125, is now rarely used. Indeed, the locomotives and carriages still form a major part of inter-city services on most main lines.

In March 2006, with rail services privatised once again, the government announced that the 125s would be gradually phased out of operation. It was to be part of the central plan to improve services for the twenty-first century.

Despite this announcement, First Great Western was clear that their 125s would continue to run on the lines to London for at least another decade.

In some quarters it is said that the engines and rolling stock can last until 2030 but, with electrification being introduced on many lines, this is unlikely to actually happen. Watch this space, as the man once said.