Scientific feuds

"Eppur si muove." And yet it moves.

Perhaps the most famous quip in the history of science, and a one-liner that encapsulates one of its most celebrated feuds - between Galileo and pope Urban VIII - over the Catholic Church's refusal to acknowledge that the earth orbits the sun.

From such epic conflicts to mere petty squabbling, scientific progress has been dogged - and in some cases propelled - by personal rivalries and intellectual animosity.

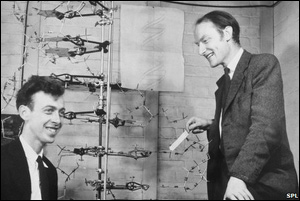

We're treated to another fine example of that genre today, with the publication of a cache of missing letters and papers belonging to Francis Crick - the scientist who, along with James Watson, first described the structure of DNA.Crick died in 2004 and it had been thought that much of his early correspondence had been lost. "Thrown away," as he claimed, "by an over-efficient secretary." In fact the lost papers - nine archive boxes of letters, postcards, notes and drafts dating from 1950 to 1976 - had been muddled up with those of his colleague and room-mate Sidney Brenner.

What we get from this lost correspondence, published in the latest edition of the journal Nature, is a vivid insight into the strained relations between rival labs, and the personal animosity between the individual scientists, involved in the DNA story.

Surprisingly the real feud at the heart of the story is not between the two teams - Crick and Watson in Cambridge, and Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin at Kings College London - but between Wilkins and Franklin themselves.

"I hope the smoke of witchcraft will soon be getting out of our eyes," writes Wilkins to Crick of Franklin's imminent departure to Birkbeck College in 1953.

Speaking on the programme this morning professor Ray Gosling, who was a PHD student in the Kings lab at the time, recalled running down the corridor between the two, trying to get them to embrace - something he admits he failed to do.

"That's my undying regret, because it could have been such a powerful effort."

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

It's entirely possible that the names Wilkins and Franklin, rather than Crick and Watson, might for ever be associated with the discovery of the structure of DNA if only they'd got on a little better.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.