Inconstant constants

With apologies to the founding fathers, the Declaration of Independence might as well have included a line about the universal constants alongside the unalienable right to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness," such is the faith placed in the immutability of these numbers.

From the speed of light to the pull of gravity, the physical constants are the yardsticks by which we measure the universe. The physical laws, according to Einstein's principle of equivalence, apply equally everywhere in the universe and always have.

Until now that is. According to research submitted to Physical Review Letters, the value of Alpha - the fine structure constant that describes electromagnetic interactions - may vary depending on where you look in the universe.

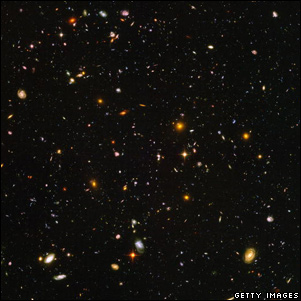

The study, by a team from the University of New South Wales in Australia, used the Very Large Telescope in Chile to analyse the light emitted from distant galaxies. They found a value for Alpha very slightly higher than that measured in the laboratory here on earth.

Even more mysteriously, the strength of Alpha seemed to imply directionality, with a large value at one "end" of the universe and a low number at the other.

"It is a surprising finding," says Professor John Webb who lead the study, "but one with fairly profound implications for the physical laws governing the universe. If one of the fundamental constants varies with position in the universe, perhaps the others do too".

In order to see this content you need to have both Javascript enabled and Flash installed. Visit BBC Webwise for full instructions. If you're reading via RSS, you'll need to visit the blog to access this content.

One conundrum that a variable Alpha could help to solve, however, is the fine tuning problem - the fact that the universe seems to be set just right to allow life to evolve.

If the constants vary, then there might be locations in the universe - perhaps large parts of it - where the physical conditions were not conducive to life. The "Goldilocks zone" becomes just one small patch in a larger, dynamic universe.

But if we can't be sure that the physical constants really are, well, constant, we can't be sure of anything.

Perhaps the force of gravity or the speed of light are mere local phenomena. In that case, perhaps we don't need to invoke dark matter or dark energy to explain the apparent contradictions we see when we look at distant galaxies.

As John Webb puts it, "Maybe the universe is just much more interesting than we've been thinking".

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

Comment number 1.

At 18:31 10th Sep 2010, newlach wrote:I am no scientist, and I have always understood that the universe is governed by significant constants. I cannot comment on the importance of "Alpha" (first I've heard of it!), but I would like to know a little more about why it is important.

In the audio Tom says of the "Goldilocks Hypothesis" that: "everywhere in the universe appears just right for life". Is this not contradicted by what is written here:

'The "Goldilocks zone" becomes just one small patch in a larger, dynamic universe.'?

Does anyone know how many "universal constants" astrophysicists use when crunching their numbers?

Complain about this comment (Comment number 1)

Comment number 2.

At 20:05 10th Sep 2010, Fr Ian Page wrote:Two comments:

1)Where does this leave the Big Bang theories? Are there any that don’t presuppose that the universe is isotropic & homogeneous and that the fundamental ‘constants’ really are constant? They always depended upon a huge extrapolation: - perhaps the time has come to stress the caveats a little more.

2)Where does this leave Prof. Hawking’s recent remarks? Are the laws of Physics, with which we are familiar here and now, inevitable or contingent?

Complain about this comment (Comment number 2)

Comment number 3.

At 07:33 11th Sep 2010, majhium wrote:Though I do have a science background what continues to amaze me is the shear arrogance of human beings and even daring to believe we know anything about the universe at all! And that we can suggest that certain values apparently are constant. We live on just one planet circling one star in just one galaxy which contains approximately 100 billion stars and we believe 80 billion galaxies in our visible universe though we also believe the universe is possibly infinite... Everything to do with the universe usually has the word "theory" behind it... Who exactly are we as a species to say constants are right or even exist! For our miniscule part of the universe only possibly!

Complain about this comment (Comment number 3)

Comment number 4.

At 23:44 12th Sep 2010, Dusty_Matter wrote:There are at least 12 physical constants, of which the speed of light and the gravitational constant are probably some of the two most often used by astrophyicisists.

This Alpha constant study has not been completely verified, and it’s possible that this slight variation could have some other cause rather than it being inconsistent directionally in the universe. It may be some local phenomena, either equipment wise, or such, that may have caused this discrepancy.

It doesn’t alter the Big Bang theory in any way. The universe still had a beginning, and this fact that the universe is expanding, of which we have observational proof, will not be altered due to this. If it’s true that the Alpha constant does vary, then it will only add to our discovering more interesting details, but it probably will not change any fundamental discoveries much.

It does seem reminiscent of the anisotropy dipole affect found in the CMB caused by our local motion in a particular direction in our galaxy. Perhaps this discrepancy was caused by the earth’s motion, and once this is accounted for, there may be no Alpha constant inconsistency. Either way, it needs to be studied more before jumping to any outrageous conclusions.

Does the lower end of the Alpha constant studied in the opposite direction of the universe have lower readings than those found in the lab, or is it still higher than that found in the lab? Do all of those readings stay higher than those in the lab, or are the lab readings in the middle between these two directional readings?

Complain about this comment (Comment number 4)