From 1 to 10,000 human genomes

If the sequencing of a single human genome - the complete genetic blueprint for an individual person - was an astonishing achievement, a breakthough to rival the first landing on the moon, then what price 10,000 genomes?

If the sequencing of a single human genome - the complete genetic blueprint for an individual person - was an astonishing achievement, a breakthough to rival the first landing on the moon, then what price 10,000 genomes?

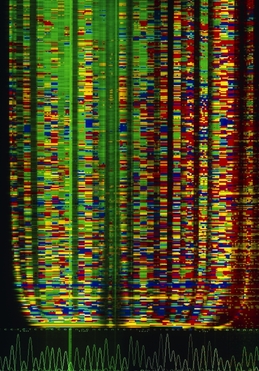

Ten years, almost to the day (the actual anniversary is on Saturday), after British and American scientists "flopped over the finish line" clutching the first 3 billion letter draft of a single DNA code, the Wellcome Trust is launching a project to sequence 10,000 human genomes over 3 years.

The project, known as UK10K, is expected to reveal many of the rare genetic variations that give rise to disease. It will involve the sequencing of the genetic codes of 4,000 healthy volunteers, and another 6,000 who are known to suffer serious medical conditions including neuro-developmental disorders, congenital heart disease and obesity.

The hope is that by comparing the genetic codes of so many individuals, researchers will be able to tease out the subtle variations - the individual genetic mutations - that give rise to disease.

The project has been made possible by astonishing advances in the speed - and corresponding fall in cost - of genetic sequencing. If Moore's Law dictates that computing power doubles every 18 months, then gene sequencing technology is well ahead of the curve, doubling every year.

"The pace of technological change is extraordinary," says Dr Richard Durbin, who will lead the project. "It took a decade to unravel a single genetic code. Now we can study the genome sequences of 10,000 people in three years".

Speaking on the programme this morning the two scientists who lead the original project to sequence the human genome, Sir John Sulston and Professor Francis Collins, said medical science was rapidly approaching a tipping point where genetic insights would start to transform patient care. Within five years genome sequencing would be commonplace - a basic part of everyone's medical records that would inform decisions about lifestyle, and which drugs would be appropriate for them and at what dose.

"We've really arrived at a revolution here," says professor Francis Collins. "It's coming gradually, not overnight, but it is transforming our understanding of biology and medicine".

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.

I'm Tom Feilden and I'm the science correspondent on the Today programme. This is where we can talk about the scientific issues we're covering on the programme.